Late in Makala, lead subject Kabwita, exhausted after innumerable tribulations, enters a church for spiritual renewal. The preacher declaims that the Book of Job shows that, no matter how much suffering one faces, blessings are still guaranteed. Anyone who’s read the Book of Job will recognize that he is proselytizing the exact opposite message from what most scholars take from the text, which is that the whole point of the story of Job is that there is no sense to suffering, and often no reason for it whatsoever. Kabwita fervently prays on regardless. He has to cling to the hope he can find.

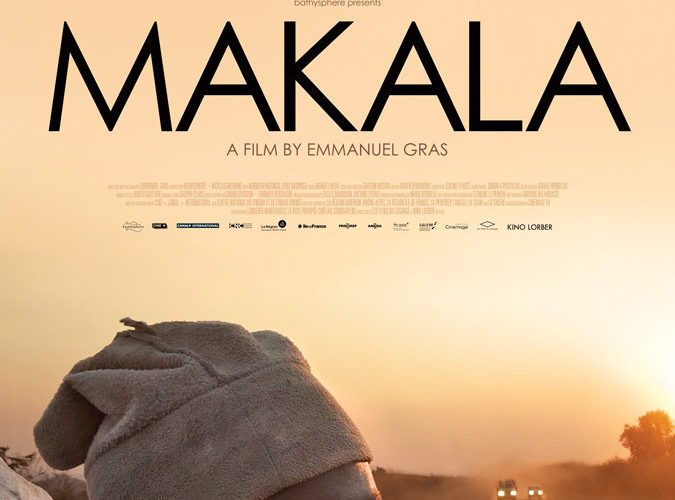

The documentary follows Kabitwa over the course of perhaps a week, watching as he plies his trade as a charcoal seller. A top-notch process documentary, it begins with a single intact, thick tree, which over an agonizing day Kabitwa manages to fell on his own with just an ax. Over subsequent days, he chops up the tree and burns the wood into charcoal – again, all by himself. He goes over what his young family needs with his wife, mainly medicine for his infant daughter and metal roofing for the house he wants to build. He stuffs the charcoal in sacks and piles them onto one bike, a preposterous construction which looks like it should not stand up for one moment, a masterpiece of ingenuity.

Makala channels its lead’s steely, steady nature. He works thoroughly and methodically, tackling each step as he comes to it. Much of the story concerns his 50km trek across the Congo to a town to sell his charcoal. The camera repeatedly maneuvers to emphasize his relationship to his cargo. One shot breathes with Kabitwa as he readies himself to trudge up a steep hill. Another lets a seemingly endless road stretch out before him, the overloaded bike at his side. One absolutely indelible image centers the heap of charcoal as it sits by the side of the road, with Kabitwa off to the side, resting and considering his task.

The journey is reminiscent of Pilgrim’s Process, in which the allegorical figure Christian carries his burden of sin on his path to salvation, but here rendered in capitalistic instead of religious terms. Like Christian, he is accosted by calamity, with a truck thoughtlessly knocking over the bike or a highwayman demanding a tribute for safe passage. The worst part is that, unlike in Bunyan’s tale, there is no guarantee of salvation at the end of the road. Indeed, when Kabitwa finally reaches the town, it is late in the day and many of the best deals have already been made. It is after the last sack is gone, little or no profit having been made, that Kabitwa staggers into that chapel. His faith is unshaken, but the audience is left with disquieting questions around how much hard work truly gets anyone anywhere.

Makala screened at the 2018 True/False Film Festival and opens on August 24.