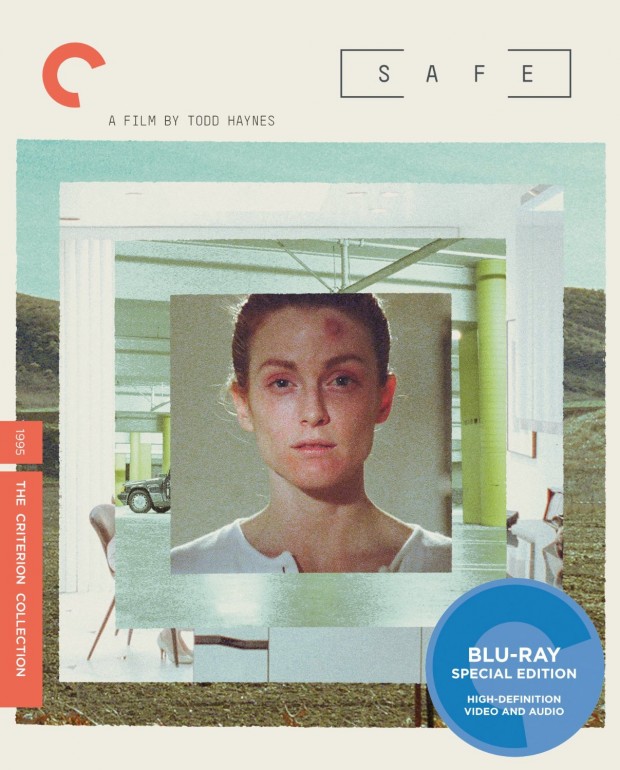

Todd Haynes‘ 1995 film, Safe, turned the high-life of San Fernando Valley into an absolute nightmare. Some would argue that’s not exactly a difficult task, but never before had perms and manicures been so frightening. The mundane life and home of “homemaker” Carol White (Juliane Moore) is a disease. When White confronts this illness her life, in some ways, gets worse. Even in a warm, sunny and wide-open environment, White’s state doesn’t improve, or maybe it does. It depends on what one takes away from White’s deeply internalized journey, especially with the haunting final shot.

White’s story is finally coming to Blu-Ray, thanks to Criterion. Perhaps one day the company will release two of Haynes’ other films, I’m Not There and Far From Heaven, both of which are sadly only available on DVD. While we keep our fingers crossed for those Blu-Ray releases, let’s just be happy Safe has been given the Criterion treatment, meaning more people will discover Haynes’ unsettling horror film.

Haynes, after recently finishing up some work on his latest project, Carol, was kind enough to make the time to discuss Safe with us, in addition to his body of work, his thematic interests, and, of course, Portland and Cincinnati:

I’m guessing you’ve revisited the film a few times now for the Blu-Ray?

Yes, I did. I was in New York while they were doing color timing and correction. We weren’t able to locate the original soundtracks of the sound elements, but they did the best possible polish they could do on what we had. It was a great process. Everyone involved was so engaged and cared so much.

Are you someone who can watch their work without thinking about what you could’ve done differently? How do you see Safe now?

Oh, yeah. They’re from such distinctive, separate times of my life. There are little things here and there you realize about budget, time, and perspective, and you wouldn’t mind polishing up. For the most part, I try to let them be what they are, even as much as this little movie I threw on [the extras] I made when I was a child in high school. I didn’t have a copy of it in my possession for years and years, but one of the guys who worked on the movie when I was in high school just wandered into Goldcrest Post in New York City, where I was working on this feature. He told me his father passed away, and his father found a copy of Suicide in his attic. I was, like, “Whoa.”

I was working with Issa Clubb on the Criterion release, and I mentioned to Issa this film of my deep past that had fallen in my hands. Isaa was like, “Oh, my god! Let’s put it on the special features!” I didn’t even get a chance to watch it again before I said sure. I did finally watch it on the plane as I came back to Portland, and I thought, “Holy shit.” [Laughs]

You kind of gotta let go, man. It’s your past, you have it all out there, and try not to get too neurotic about correcting the past. Safe is a film completely from a time and place I respect. I do feel it’s weirdly relevant, even with certain changes — at least in the culture of HIV and AIDS, which inspired me to a large degree. Not to say other similar panics around illness or contagions don’t continue to stay with us or return to us as a culture, because we have plenty to look at today. So, yeah, it’s really great to have it out there.

Your depiction of San Fernando Valley remains relevant as well. Sometimes that place makes you feel like you’re on a different planet.

Yeah, yeah, definitely. I felt that way watching it, and I still feel that way about LA: everyone is sealed off in their separate vehicles. There’s a glassed-in feeling about life in Los Angeles, and it’s quite different from life in the East Coast. I remember thinking of the films of Stanley Kubrick and 2001, and trying to infuse suburban life with that weird sense of being in a completely controlled environment, where there’s conveyer walkways, carpeted walls, and where nothing feels it’s been bruised by human soiling. It’s beyond human, in a way. You find this fragile subject, Carol, at the center of this alienated life and world, which really does come through. It speaks a lot to that city.

I was just reading an interview with you where you said moving to Portland, in a way, rejuvenated you. As a filmmaker, do you find it beneficial not living in a place like Los Angeles, where you do interact with people on a daily basis?

I do. I definitely do. What’s funny is, we carry around our own orbital patterns of life, the ways we fall in domestic life, and the way we fall into a pattern of life — and that’s natural and normal, but you kind of carry that with you wherever you go. What’s really great is — and many filmmakers happen to have this built into their lives — you have to move around quite a lot, and not be in one place, even if you have a home base, like I do in Portland. I love it. I still feel a tremendous amount of relief when I come back here, because it’s a beautiful, vital, and exciting city. It’s a bit of peace and quiet. I was just in New York for an entire year for my new film, Carol, and it was great. It’s fantastic to be there. It never felt completely real; it felt a little imaginary. I was there for post-production, but I was in Cincinnati for the first half of the year.

Great city.

It really is a great city. I really, really dug it. I was so surprised where we landed, but once we saw what the city had to offer, it made so much sense for a film set in the ’50s in New York. I really like the people and the place. It’s obviously a city in transition, like a lot of second cities in this country are today. There was surprising stuff, like using non-union extras, local folks out there as our background. Not only did they look so good in the period clothes and hair, but they just looked like real people. They really performed well and felt totally at ease, and I don’t always feel that way with union extras, who kind of do it automatically. These non-union extras had these imprecations and the human blunder of real people, and I just love that because it brings a great deal of life and authenticity to what we were doing.

I imagine that working with those extras is different from the experience of Safe, where Carol is isolated for a considerable portion of the film. How was the experience of working with an actor one-on-one for so much of the production?

Well, it’s great. It’s impossible to overstate the experience of working with Julianne on Safe, and the projects that followed. I don’t think I ever wrote or conceived of a more challenging character on the page for an actor to embody than Carol White, who’s just so absent from herself when you first encounter her. There’s so many barriers set up for the viewer’s access to her that we usually come to expect from movies, not the least of which is the fact she’s not a very fleshed-out or interesting person. Initially, Julianne had total respect for that predicament: the fragility of the interior world of Carol White. Julianne not only respected the character and the person, but also the filmmaking, which really distinguishes her from a lot of actors.

Julianne really thinks about what the stylistic language of the film is and what the frame is, and she really wants to work with directors who have a strong sense of how that process can be articulated in different ways to serve different kinds of stories. She understands that, so she doesn’t try to fill in as some actors, understandably, feel compelled to do, to feel they’re helping the viewer out. Ultimately, Julianne recognizes viewers have incredible intuition, and power of reading information on the screen, and reading narrative form and style.

An audience’s hunger for stories to unfold a certain way are actually opportunities actors and directors have at their disposal to illicit but also betray, play with, or toy with — and we were certainly doing some of that with Safe. She really trusted me and the writing, but, ultimately, it’s the trust in herself that gives her the ability to underplay and let an audience find you in the frame, and not always be waving desperately for their attention. She’s really extraordinary that way. When I saw it again recently she… I’m proud of the film, but it rests entirely on that performance. It’s an inconceivable piece of work without someone as powerful as Julianne at the core.

Is it rare for an actor to ask about framing to inform their performance?

I have to say, the really extraordinary actors I’ve worked with really do care about the frame. Sometimes it’s even just simply… when I was working with Cate Blanchett on I’m Not There, she was playing a man in this role of Jude. She would look at playback. She didn’t look out of a sense of vanity; she just wanted to see how her hips were being filmed and how to place her body in the frame to minimize the broadest curves of her female hips. Sometimes it’s very technical reasons why actors want to see what the frame is. It’s all relevant. It all plays into what is the language and the style, and how is that style informing the interpretation of the storytelling and character. I find some of these extraordinary people I’ve been lucky to work with ask questions about the frame, and it’s always for reasons of how they’re going to interpret their performance accordingly.

The framing of Carol, especially when she’s alone in her oppressive home, is haunting. Home usually plays a major part in your films: In Velvet Goldmine Christian Bale’s character has to hide who he is in his home; there’s an isolation to the home in Far from Heaven. The ideas or themes that tie together your work, are they an intentional exploration on your part or is it all subconscious?

It’s a good question. It plays in very different ways in very different films. The two examples you mention are almost on the opposite poles from each other. In Safe, Carol’s introduced almost as one of the objects of her house, almost competing for a sense of importance or presence with the objects in her house. She ultimately comes to realize there’s tremendous danger within the walls of what would otherwise be described as the American dream home: full of all the material comforts we covet as a culture.

It’s very much like the Sirkian homes, from Douglas Sirk‘s films, which are these magazine images of idyllic dream interiors. The clothes, costumes and stylings of those films only contribute to that sense of an almost unbearably perfect domestic life, that none of the subjects in these films can quite live up to. Their limitations as subjects or characters is what’s so poignant about those films — that they’re not nearly as gorgeous, heroic and victorious as they look. There’s a sense of loneliness and despair living amongst perfection.

In Velvet Goldmine, it’s a very different moment. It really is the secretive moment: he has to lock and wedge the door shut before he explores something that is wholly available at the record store down the street. He unlocks a channel of discovery, erotic surprise, and danger that, you know, one would think has no place in that suburban house. As it turns out, it precipitates into him having to leave his house, which threatens his domestic relations. You know, I love how that sense of danger and the unknown exists next to the absolutely domesticated and familiar objects we’re surrounded by.

With Carol White, I didn’t want to create a perfect life her illness begins to undermine, because I actually wanted something to be wrong about this life. If anything, the illness leads her to an opportunity to see there’s a discrepancy between this life and something else. The illness alerts her to a hint of danger that is signified by the world around her, in a way that’s the beginning of some crucial discovery about her own despair, grief, and own distance from that life and herself she otherwise never would’ve had the opportunity to encounter.

Are you a writer who thinks about themes and what a film is saying?

I have to say, I do, without necessarily putting it that way — like, what the film is saying. I do have some questions about the world around me that I feel the setting, the place, or genre can help me expose or get deeper into — or, in some ways, just teach me more about. It’s not necessarily so much the story but the occasion that inspires me as a writer or director. In some ways, I feel like the story can be a masking over the real core issues in films, and the ways those issues break through the story or upset the story or interrupt the story are the best chances for us to learn something new or say something different.

I like genre, because it sets up expectations in how stories should move. Ultimately, I think it’s about the ways in which some films take those expectations and twist them that take us to a different place. There’s something about Safe where I wanted your own narrative expectations to first drive this woman out of a certain kind of oppression, and then ultimately drive her back into it. The Renwood world is suppose to be this place of answers and cures for illness, but it puts her back into a place of total inclosure, which is very much how we found her at the beginning of the story. We want resolution. We want movies to wrap themselves up. It’s that very desire for resolution that can often inflict a kind of torture or abuse on the characters themselves. I love that you can follow those steps to the “happy ending,” and yet Safe is anything but, because it raises all these kinds of questions.

It’s funny, when I watched Safe I thought of Far from Heaven, because Sirk is famous for his happy endings that aren’t really happy endings. You don’t really trust the absolute wrapping up or the solving of the problem. In a way, my ending of Far from Heaven is not exactly a Sirkian ending, because it’s kind of full of despair and loss. When I saw Safe, I thought, “That’s a Sirkian happy ending.” Carol follows all the steps and says she made herself sick and says all the things people are telling her to say, but you know, in your heart, that’s not really what you want for her, but it’s sort of what society tells us what we’re supposed to do. I got my Sirk ending in there somewhere. [Laughs]

That’s great. Before I let you go, I have to say we’re very excited for Carol at the site. How is it coming along?

I’m so happy. It came out beautifully. We literally just finished completing all the deliverable requirements for it. It’s weird, because it’s so late in this year, but there was no way to make any festival’s deadline for it. We all thought it would benefit from a festival launch, so we decided to wait. It’s not going to come out until next year, and it’s going to be torturous to wait that long.

You know, it’s set in the ’50s, and it’s a very different kind of ’50s film than Far from Heaven was. The feel of it is much less inspired by ’50s cinema, and more by, I guess, photojournalism and a lot of the art photography we were seeing at the time, which has much more gritty… it’s a very poised film, because it has a real sense of control to it. The look of it is much more distressed.

It’s set in the early ’50s, before the Eisenhower era had really taken hold. It was a really transformational and unstable time from the war years into the beginning to what would become the ’50s as we know them. The historical imagery and references we uncovered showed New York was really like an old-world city in great duress: very dirty, very dingy, and very neglected.

I thought it was such an interesting place to mount this, ultimately, very pure and simple love story between a younger woman and older woman at the most unexpected cultural moment and place. For me, the look of it is very unique. The performances from everybody are just lovely. I’m dying for it to come out, but it looks like we’ll have to wait a little longer.

Safe is now available on DVD and Blu-Ray from Criterion.