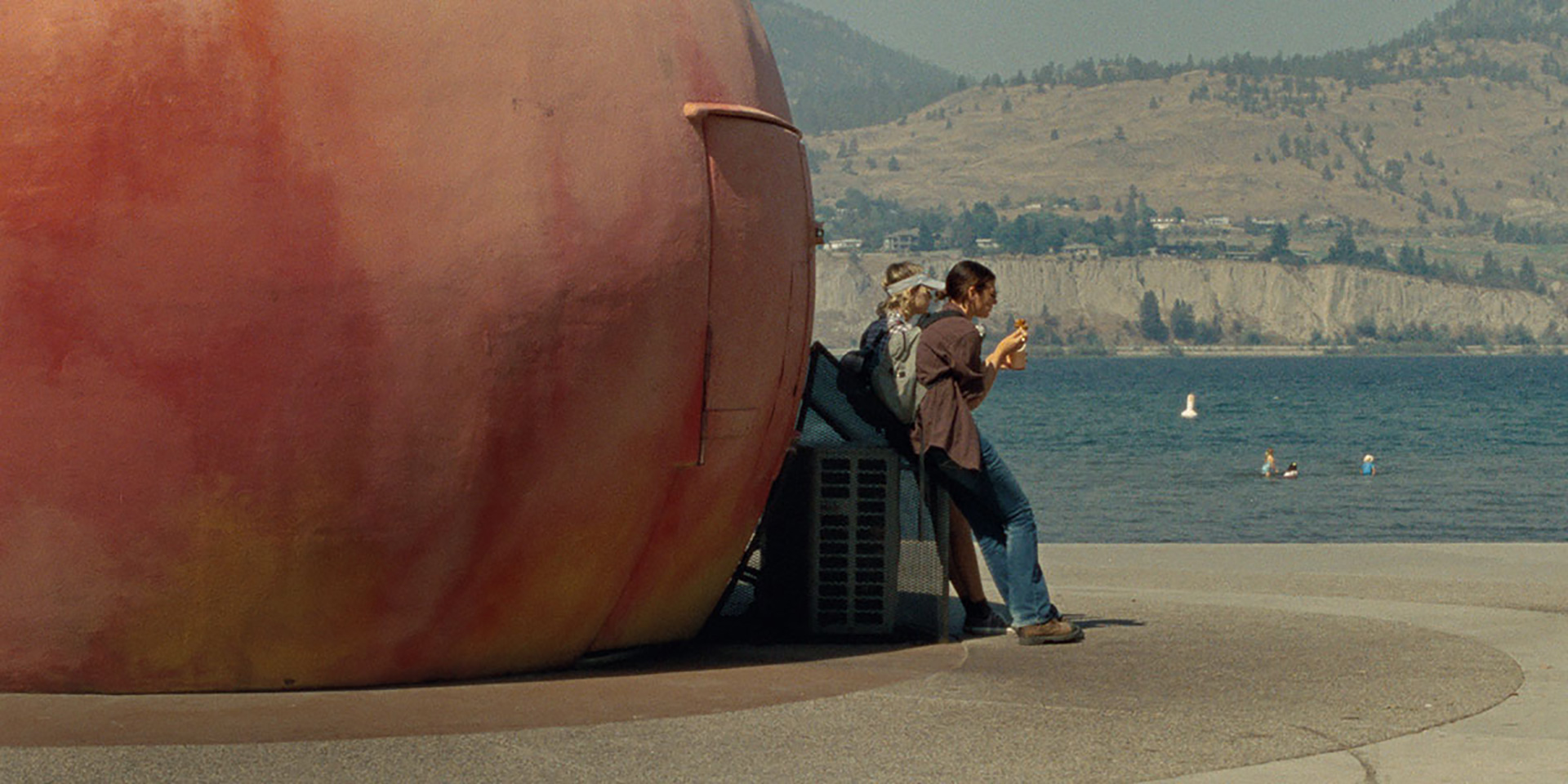

Something is amiss with Robin (Grace Glowicki) and the quiet Canadian peach grove town of Montague. An invader has taken hold. It’s wormed its way beneath the surface to incubate and grow, causing incalculable stress upon its vessel. And nobody wants to admit it’s there. Because doing that—making it real—means turning everything upside down to deal with it. Thus they bury their heads in the sand and ignore that a problem could even be feasible let alone already in progress. Unlike everyone else, however, Robin has no choice but to act and confront both the accidental pregnancy (conceived with her married boss, Lochlyn Munro’s Dennis) and the potential threat on their crops caused by what looks to be the beginning of a spear beetle invasion.

Why? Precisely because they won’t. She’s seen what happens if an infestation is left unchecked, though. Years prior, Montague all but went under from moths. Doing nothing would make her complicit. And she knows what telling Dennis about the baby would do to her job status and reputation. So she drives hours away to the closest abortion clinic to both listen to a doctor who admits the text she’s legally obligated to read has zero scientific basis and to discover she’ll have to come back another day—a purposeful, disruptive tactic to try and dissuade or prevent her from being able to terminate. Then she stops by an agricultural center on the way home to see if someone can confirm or deny her suspicions about the insect.

Writer/director Sophie Jarvis’ feature debut Until Branches Bend places both issues on parallel trajectories with overt metaphorical mirroring. The peach Robin found the beetle in looked fine on the outside. If not for a worm hole and the time of day (the break whistle just sounded) she wouldn’t have given it a second glance. She appears fine too. She isn’t showing (besides a sudden craving for deep-fried pickles at the fair) and the only person who knows about the affair (Paul Kular’s Jay) laughs with her about it. Just as she’s told she’s already ten weeks pregnant, though, the assumption is that the crops have already been polluted since branches start breaking under minimal pressure. Yet none of it matters. Closing the cannery means cancelling paychecks. That does.

The entire world is thus coming down upon Robin’s head. The province’s former conservative government made sure it would be near impossible for her to terminate the fetus. The gross financial inequity caused by capitalist greed has destroyed the environment, brought about these more regular insect invasions, and forced workers into willingly facilitating more destruction just so they can survive on what little these corporations allow them to have. Add the fact that Robin’s sister Laney (Alexandra Roberts)—the only family she has left—is talking about leaving with her vagabond boyfriend from a wealthy upbringing (Antoine DesRochers’ Fabien) and that the town has turned on her for blowing the whistle on their livelihood; she’s suddenly all alone. Well, karma is coming over the horizon.

Which, unfortunately, doesn’t excuse the strife she’ll endure before it arrives. While the film is at its core a straight-forward drama, the fact Jarvis centers everything atop Robin’s shoulders allows it to adopt traits that have it being described as a psychological thriller instead. With a discordantly unsettling score and shifts into hallucinatory dreams or compulsive behavior, we can’t help but worry about her devolving wellbeing. At a time when Robin needs allies the most, she’s stranded by those she thought she could count on no matter what and attacked by strangers who blame her for their increased poverty. The only people who have her back is the indigenous population that hopes to use this opportunity to fix the town’s faulty value system. Nobody listens to them either.

What I really like about Until Branches Bend is that Jarvis makes certain the audience knows Robin is right. We never doubt her courage regardless of whether it’s born out of curiosity more than activism. She is being silenced, oppressed, and scapegoated. She’s being abused and sabotaged in ways that render her ability to deal with her personal issues (the baby) impossible. And even when she does find support, it always seems to arrive too late due to those willing to see the truth inevitably coming from a position where ignoring it was beneficial (Jay, who runs a peach orchard with his father, and Quelemia Sparrow’s Isabelle, Dennis’ Indigenous wife). So the goal isn’t to make or break Robin. It’s using her plight to share a crucial message.

Rather than worry about the crops, we’re invested in her. She’s one person against many. One selfless soul willing to see the bigger picture beyond her own depleted bank account as the town is readying to blow the whole thing up—the work necessary to fix it seems too great when there’s a chance it might all be for naught. As we should all understand, however, it’s needed regardless. The demands of capitalism are leading us down a path of no return—one in which we’re so connected to the descent that refusing to see it becomes the easiest and most damaging defense mechanism in our arsenal. To therefore watch Robin risk her sanity to fight for truth resonates. She isn’t being reactionary. They’re being willfully naïve.

And Glowicki excels in that role. Her body revolts against her along with the town, and she’s struggling to keep breathing as more knives get stabbed in her back. It’s as much a depiction of being poor as it is being a woman of any social and economic standing. Both are dismissed. Do you stay quiet and subservient to the men in power? Do you give up on your hopes and dreams for a man who’s using you? Do you sacrifice your grandchildren’s future to bolster your present while thanking the people who are wrecking both? Duality abounds—whether Isabelle’s loyalty to her husband and her people or Jay’s loyalty to money and his community. The one that matters most is usually the hardest one to choose.

Until Branches Bend had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival.