The reason Yung Chang picked This is Not a Movie for the title of his documentary on renowned journalist Robert Fisk stems from his subject’s inspiration for pursuing that line of work. Fisk talks about watching Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent as a boy and thinking its lead led a life of excitement that most people only ever dream about. So he pursued the career despite parents wishing for another direction (before their pride of having a son at The London Times kicked in) and eventually found himself in the Middle East (where he remains to this day with The Independent) documenting the region’s historically never-ending unrest. Has he changed anything or received his happily ever after? Since his life isn’t a movie, the answer is no.

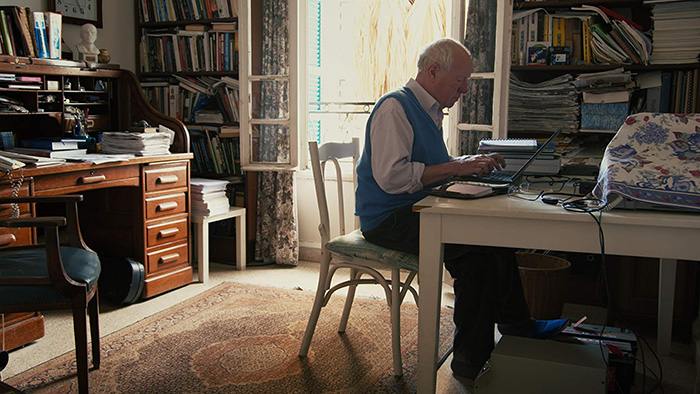

To hear Fisk reminisce about his job, comment on the present state of the press, and admit his continual interest in the story unfolding at his feet in those countries that neighbor his adoptive home of Beirut, Lebanon, however, that was never the point. For him the mission of a journalist is to record and nothing else. He can’t force a reader to comprehend what he’s written with centuries of conflict at its back. Nor can he stop them from looking at what the other side has written and decide a truth wholly different than what his own eyes have seen. All Fisk can control is his ability to hold strong to his integrity as someone documenting the objective truth no matter who gets disparaged in the process.

This is why he’s been called pro-Baathist, -Palestinian, -Zionist, and every other side in the book at one point or another during his lengthy tenure. Rather than see him as a man without sides who writes the truth no matter whose toes he’s stepping on (a trait that forced him to leave The Times after new publisher Rupert Murdoch started pulling his articles for pure propaganda), those aligned with each specific story’s antagonists find solace in discrediting him as biased. It’s something that probably happens most often when covering Israel’s human rights atrocities—a land that purposefully insulates itself from detractors by embedding its Jewish religion into the fabric of its politics. This tactic therefore lets it defame critics as anti-Semites without ever having to confront a fact.

Fisk’s candor about such issues is refreshing today considering how often we’re forced to read articles about “the other side” in American newspapers despite that other side being white supremacist racists. For Chang to have his subject call bullshit on that type of reporting is nothing short of heroic because it shows that some journalists out there are still willing to take a stand and prop the voices of victims up above those of their executioners. He isn’t immune to falling prey to that inclination himself, however. As the film goes on, Fisk very intentionally does exactly what he says he wouldn’t by interviewing a South African Zionist who says Palestinians are a fake culture. I guess his stalwart support of the oppressed is for genocides, not displacement.

I know that comparison is reductive, but the film’s refusal to confront the contrast allows me to make it regardless. There are many instances where the decision to let Fisk narrate, contextualize, and serve as lead character guarantees the whole becomes a laudatory anointment of him as the patron saint of journalism rather than a figure who himself should be reported on. Antony Loewenstein comes close to putting Fisk on the hot seat, but he ultimately lets him bulldoze the conversation (about an aversion to social media and online reporting being a dangerous generalization denigrating the good reporting done via those venues) in the name of civility with a smile. I like a lot of what Fisk says, but a bit more push back would have been nice.

This is especially true because of the great humanitarian work he has accomplished to ensure the harrowing experiences of those who have been forgotten by time got on the record so we can go back and listen again (i.e. the Sabra and Shatila massacre). Chang should thus be holding him to a higher standard—or maybe exposing this bias is part of the point because it shows how those “without” are always inherently with. I wouldn’t be surprised if this were true since one scene is included where Fisk pretty much tells two UN soldiers that he doesn’t suffer from PTSD because it would be bad for his job. As if it’s about having the mettle to dissociate and not the fact that he isn’t pulling any triggers.

I digress, though. While I would have liked This is Not a Movie to be that movie, it doesn’t discount the fact that what it is remains worthwhile. He does have interesting things to say about the media today and how readers have willfully absolved themselves of nuance when being a “hater” is an easier way to remain right without engaging in a conversation. How mainstream misinformation from tourist journalists can spread like wildfire while he’s told the opposite from those on the ground is another intriguing first-hand truth that should scare you because it’s extremely difficult to change minds once their outlets of choice have already weighed in. Fisk also understands the damage colonization wrought and he isn’t afraid to hold the West accountable for its enemies.

That courage means something. Fisk continuing to hit the frontlines of Middle Eastern wars at seventy-years old to tell his truth rather than act as a secondary source means something too. And while his tenacity and confidence does make him someone the film refuses to question, those traits also let him be the kind of devil’s advocate we need—sourced rather than opinionated. It’s too bad his kind is a dying breed as the 24/7 for-profit news cycle places higher value on editorializing talking heads than those doing the work for more than a few days at a time. Where Fisk follows a lead, uncovers details, and logically extrapolates what probably happened, cable news takes his hypothesis, makes it sacrosanct, and does more damage than good.

This is Not a Movie premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.