Interpretative dance is not something to be lightly taken. You either have the propensity to let it wash over you in its loose gyrations of emotional expression or you roll your eyes at what look to be seizures on stage. I’m probably in the middle of the pack in that I’m open to the performative aspect of the medium if not quite capable of understanding what’s happening beyond its purely aesthetic level. It helps to read an artist’s statement to delve deeper inside, but sometimes the formal enjoyment is enough to make it worthwhile. I look at it similar to a Cirque du Soleil show, which to my mind is more about the spectacle than anything else. Stephen Page might be okay with my appreciating his Spear for surface beauty, but there’s obviously much more to be said.

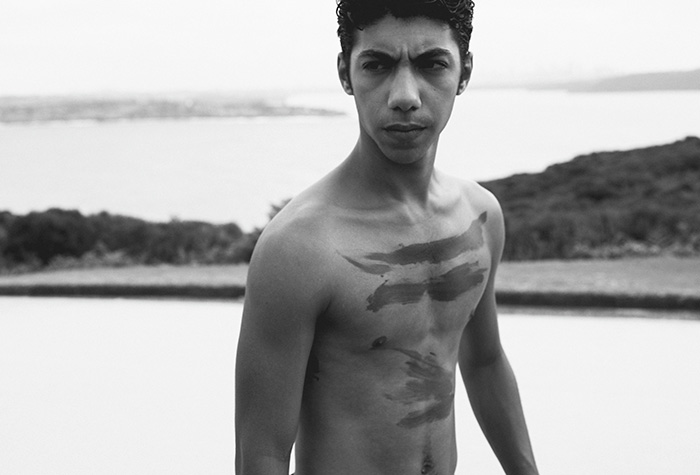

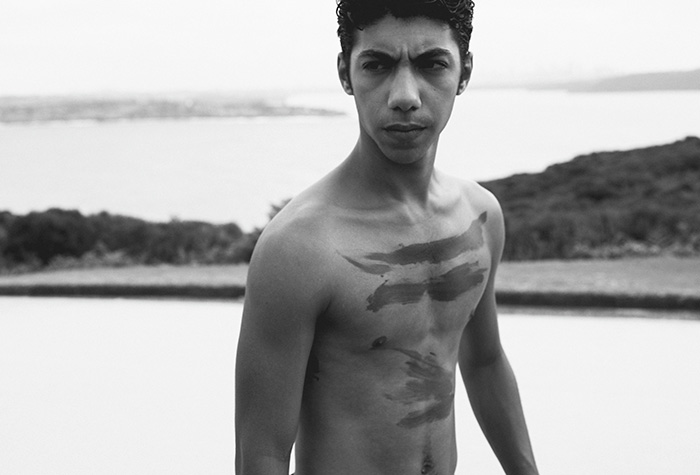

Inspired by Australia’s Bangarra Dance Theatre‘s artistic director’s 2000 work of the same name, this film depicts the journey of a 21-year old Indigenous man at the cusp of turning into an adult. Djali (Hunter Page-Lochard) begins the journey on the awe-inspiring rocks and waters of an Aboriginal community, doted on and painted to ready his escape to the city. Led by a spirit guide of sorts—an elderly, white-bearded man dragging a bag of sand for Djali to follow—our lead finds himself to be a surveyor of his people and their struggles in the modern world. Whether it be in jail, the aftermath of a car crash, or the sad story of a homeless man (Aaron Pederson) unable to ever reconcile the two worlds of his past and present, tragedy is pretty much all Djali can see.

These vignettes are called “serpent chapters” and serve as lessons for him to learn and digest along the way. The history of his people is filled with death and compromise, bigotry (Charlie Drake’s novelty song “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back” and its wealth of political incorrectness arrives through hokey dance moves within a sort of minstrel show) and aggression. Only the vision of a woman (Nicola Sabatino) to turn his head before disappearing shines as a beacon of hope and the desire for possibility beyond the tragic memories he’s forced to experience in an attempt to preach what not to do. It’s hard to necessarily embrace any of this outside world’s existential vice-grip, though, when it’s full of examples foreshadowing a shedding of skin—black turned white as culture and tradition is stripped away.

I can only infer on Page, co-writer Justin Monjo, and composer David Page‘s authenticity from their heritage, history of re-interpreting these traditional tales into dance, and the intriguing opening warning to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers about the inclusion of voices and names of the deceased. I’m obviously unable to understand what Djakapurra Munyarryun sings alongside his wood block percussion to fully comprehend each event beyond the emotionality of the movements and progression of motifs. And when white and black paint make way towards red and blue by the end, count me utterly clueless to the demarcations. All I know is that the final dance proves an invigorating conclusion of celebration—perhaps Djali’s rebirth as a man ready to face the challenges ahead.

In this respect I can only truly speak from my appreciation of the performances and the visual splendor of their convergences throughout Spear‘s duration. The music stirs your soul as the ballet engages your senses to look within and find meaning beyond what those versed in the culture know it to be. We see the compassion in Page-Lochard’s eyes as those he hopes to learn from perish; the fight and drive to prevail and overcome the too-heavy weight placed upon them. We revel in the gorgeous landscapes of trees, the darkened studios illuminated by prop lights, and the unforgettable visage of a spirit writhing upside down, covered in paint/ash/earth/etc. The spirituality of each movement becomes the key and it’s up to us to willingly allow it to be enough.

Page’s work is obviously not for everyone, but that doesn’t lesson its motives or success. He has definitely transferred the energy of a live stage show to the screen, enhancing it with real locations for an unconstrained vision worthy of its universal coming-of-age dramatics. Bonnie Elliott‘s cinematography uses a lot more close-ups than I expected given the scope of its moving parts, but that decision helps bring us closer to Djali and the actions of those surrounding him as individually and personally complex rather than cogs inside a performance whose scale is paramount. This movie’s very much about the pieces and the lessons they bring. We must see their every flourish and expression to know what it is they feel. That’s the part we’re all capable of understanding regardless of heritage or language.

Spear makes its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 11th.