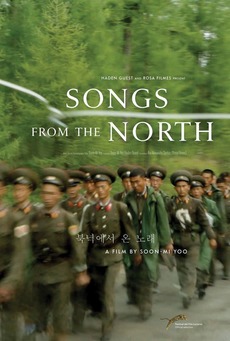

“Dictatorships are banal” might be the main thesis of Songs from the North, a curious essay film from Soon-Mi Yoo (who contributed a segment to Far From Afghanistan). The cultural vision of North Korea is certainly one that often feels limited here in the United States: CNN specials about horrors under the reign of their three Kims (Il-sung, Jong-il, and Jong-un), oddball visits by Americans like Dennis Rodman, and, now, a standard enemy in films like Red Dawn and Team America: World Police. (This is to say nothing of an especially odd thread running through David Cronenberg’s upcoming novel, Consumed.) In that regard, Yoo’s film is a necessary correction of how we should view or think about what life is really like in North Korea, even if the work feels somewhat limited by its own necessity.

Yoo has a personal stake in this, after all. Her father (interviewed in the film) fought in the war, and many of his friends abandoned their lives in the South to become denizens of the North. More artistically, Yoo notes in a recent interview that most documentaries are “very one-sided, and they didn’t actually reveal anything about North Korea beyond what we already knew: it’s a terrible place, people are under this terrible tight grip of the regime, and they are poor and brainwashed and so forth.” Appropriately, Songs from the North oscillates between Yoo’s own footage from inside the country and media artifacts she has dug up, from classic movies to filmed theater to an advertisement for Korea’s space program. Those images are quite fascinating to watch for numerous reasons, not in the least that it’s fun to see North Korean cinema to go through the same aesthetic movements as the rest of the world. Sea of Blood (1968) is reminiscent of Eastern European New Wave pictures, a melodrama like Bellflower (1987) shows the influence of MTV-style cutting, and Traces of Life (1993) has the same kind of action one expects from Arnold Schwarzenegger’s work.

The real-life footage by Yoo, however, is both insightful and somewhat frustrating. Yoo often composes from a distance, observing the country’s people moving from place to place during their daily commutes, or a woman cleaning her restaurant after a night of business. There is something bold about capturing “nothing” in this country, but the banalities rarely transcend beyond being banalities. It would be interesting to see into schools and offices, municipal departments or movie theaters. Because of the nature of Yoo’s project, she is limited to public spaces, and even there does she exhibit restraint. Her intention is clear, especially in one sequence where she follows people walking on a cold wintry day and ponders the propaganda radio that echoes in the background, but its repeated sequences offer less insight than they initially denote.

But Songs from the North is not meant as a final note of how to interpret what life may be in a country that is constantly skewered by our media. I appreciate Yoo’s choice to never speak in an authoritative voice—she eschews voiceover for a text overlay on a black screen, which works almost like a call and response. Some of the more fascinating statements she makes, especially about the desire of the North Korean people to reunite with the South, offer promising glimpses into a culture we know little about. If this is only the first in a series of essay films Yoo can produce, she may evolve into one of the most essential voices in world cinema.

Songs From the North screened at TIFF and opens on September 18th, 2015.