The 1969 Sir George Williams Affair seems like something we should all know about. It occurred only a year after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and proves a defining moment in race relations throughout Canada, yet it’s taken over four decades for someone to document what happened during its fourteen-day student demonstration of civil disobedience. The importance increases even further when you think about where it happened—our neighbor’s up north with a reputation of open arms and tolerance to which we couldn’t dare compete. And with the successful Expo ’67 having just ended to reinforce that view on the world, seeing what was actually happening becomes even harder to stomach. It wasn’t merely a matter of one man’s prejudices either. It started that way, but quickly escalated into exposing an administration-wide show of bigotry and inequality.

Filmmaker Mina Shum is behind Ninth Floor‘s look at this historic event for someone like me stateside with little knowledge of Canadian history and less of Montreal. She has culled together a rather robust group of primary sources to set the record straight, explain motivations, and even add a bit of subjective commentary on who may have been at fault for the fire that damaged two million dollars worth of school equipment and ended the otherwise peaceable standoff with almost one hundred arrests. Of the six Black Caribbean students who served as the original complainants towards Professor Perry Anderson for treating them differently than their white colleagues, two (Terrence Ballantyne and Rodney John) are prominently featured alongside a handful of the almost two hundred protestors from George Williams and adjoining schools that stood beside them.

The evidence is pretty damning with stories about Anderson calling his Caribbean students by “Mr.” and “Mrs.” while using first names for everyone else and another where one let three classmates copy his lab to which they got 10s and he only a 7. What should have been a cut and dry inquisition, however, became anything but. Rather than address the concerns of their paying and intelligent students—many from wealthy West Indian families—the administration dragged their feet. They waited months before putting together a committee to hear the complaint and then replaced the only two black professors with whites without consulting the students due to a “communication breakdown”. It was obvious they were trying hard to end the situation without having to actually confront the issues and the complainants were not going to let that fly.

What transpired was a sit-in on the ninth floor of the university housing the school’s computers. Hours turned into days and days into over a week before progress finally seemed at hand. With trust already wearing thin, watching that sign of moving forward dissolve as yet another lie turned peace into action. Students who cleaned up after themselves and took pains to ensure the floor was left the way they found it were replaced with those housing more anger. Property was willfully damaged, computer cards thrown out the windows, and all entrances and exits barricaded. It was only then that chaos prevailed with the police ordered in as smoke billowed out and chants to let the students burn turning an ugly situation grotesque. The biggest student uprising in Canada’s history exposed how fear bred the exact thing feared.

Hearing the details from the mouths of those who lived it lends a credence reading the newspapers never could. It doesn’t help that the media almost always sides with law enforcement because they are at their disposal to interview. Only in the aftermath do we discover police officers planted inside the protest and hear how peaceful the demonstration was before the administration failed them for the last time. What’s most memorable, however, is listening to talk about implicit and explicit racism: about how someone raised to think all black people were violent will of course fear for his life when confronted by five threatening to keep him detained until their demands are met. One recent student even speaks about never thinking of himself as “the other” until becoming the only person of color on his campus circa 2010.

It isn’t just the Caribbean-born fighting either as Robert Hubsher is featured extensively too. A man of Jewish descent, he speaks about his own experience with racism as a child and how it impassioned him to join the cause of his fellow man in 1969. This was never a black versus white issue, but instead one that sought student rights no matter color or ethnicity. The way it escalates ultimately turned the attention away from Professor Anderson (who refused to be interviewed, but whose son is) and onto the school itself to pave the way for Ombuds offices through the nation. Shum’s story progression expertly traverses the months before and after the incident with a wealth of detail and archival footage placing us in the mix. We witness the tension and watch how intentions are replaced by preconditioning.

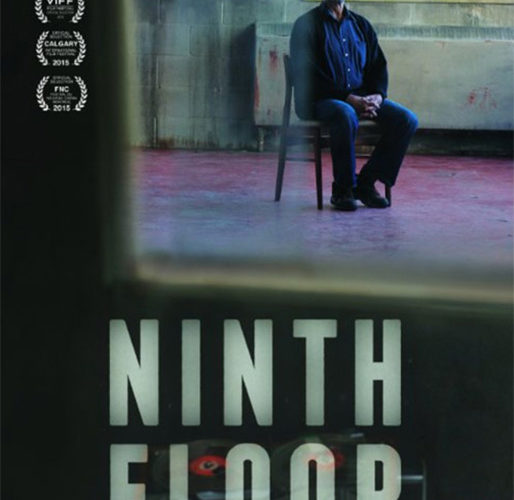

Sprinkled in with the newsreel footage, article headlines, and interviews spanning Ballantyne, John, core complainant Kennedy Fredericks‘ daughter and Nomadic Massive member Nantali Indongo, and fellow protestor Senator Anne Cools are staged interludes of silent contemplation with subjects alone or together. These scenes serve as bridge material to introduce interviewees, but also ruin the otherwise carefully constructed document of unfiltered opinion. More glamour shots than possessed by substantive merit, I won’t deny they took me out of the truth. It’s a small misstep, though, merely adding to the already high production value media filters mimicking loudspeakers and surveillance monitors—themselves interesting choices if only for aesthetic purposes. Less flash might have done the story better justice, but I cannot blame the filmmakers for wanting to render the whole palatable to a broader audience with some mainstream convention.

Ninth Floor makes its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 12th.