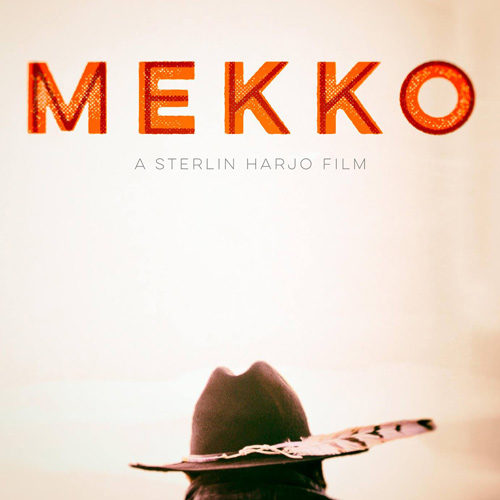

Seeking to bridge the divide between contemporary filmmaking and Native American spiritualism, writer/director Sterlin Harjo‘s Mekko provides a tale of redemption and honor worthy of both worlds. At the center is a kind-hearted soul damaged by alcohol and dark forces stemming from his old hometown’s need for evacuation due to its water supply. Caused by the proximity of a lead mine, Mekko’s (Rod Rondeaux) grandmother would spin a tale of witches and evil they needed to escape before being consumed. He did get out, but perhaps not soon enough as the road he and his artist cousin John roamed led to a tragic end with one dead and the other incarcerated. Harjo drops us into Oklahoma nineteen years later as Mekko returns to the outside in search of forgiveness his family refuses to give.

He instead finds himself in a neighboring city amongst Natives like him relegated to the streets. It’s an inspiringly close-knit group where every newcomer is greeted with the decree that he can ask them for anything. “If we can get it we will and if we can’t we’ll help in some other way,” says one gentleman upon Mekko’s arrival. And it’s not long before he himself takes up the mantle of greeter, charitable with his time and assistance to all less as a penance for his past and more a result of simply who he’s always been as a man. Keen to remain sober and give back to the community he was forced to leave behind, he’s paid back in respect. Only a loose cannon named Bill (Zahn McClarnon) stands in opposition with ulterior motives and blackened heart.

What follows is a straightforward tale of one man trying to survive a hopeful rebirth. Now a wise, sage-like hero still wrestling with his own demons on a mission to protect others so they won’t suffer the same fate as John, Mekko spreads love with his easy smile and affable demeanor. The waitress at the local diner (Sarah Podemski‘s Tafv) takes a shine to him, helping out with leftover food and a kind ear of reverence for his “chief.” An old friend (Wotko Long‘s Bunny) crosses paths for an unlikely reunion, providing advice on the new surroundings. These two plan a return home so they can gauge whether the evil has dissipated to allow for its renaissance. But the threat of their current stomping ground being overcome by its own witchcraft gives Mekko a spiritual quest for justice.

Juxtaposed with narration that delves into the past, his grandmother’s stories prove cyclically relevant to the present. He’s the light and Bill the dark, both on a collision course in the physical world and beyond. There’s a lyrical quality to these passages with the black and white vignettes of memory cutting through the harsh reality of now. A foreboding sense of dread creeps in from the fringes to gradually steal Mekko’s smile and replace it with fury. Tragedy strikes again and again until the darkness arrives in the guise of a bottle and we wait for morning to see which version of him surfaces. A dramatic thriller at its core, the film is made uniquely exotic by the addition of its Native American folklore. Harjo’s hybrid becomes a captivating parable in this conjoining, simultaneously relatable and abstract.

It’s a slow progression from start to finish in most part because the titular character is so contemplative and exacting. We must watch as he embeds himself in this new community, accepting him at his word to be different and witnessing just how dedicated to that cause he is. Harjo doesn’t shy away from painting him as a man who did his time with reason either—the deed may not have been intentional or malicious, but it took a piece of his soul nonetheless. It’s this concept of a soul being the fire burning at the center of everything that strikes the biggest chord too. It remains lit as long as you believe it so and even though Mekko laments that his is long gone, there must be a few embers breathing oxygen somewhere within.

There are definite production issues due to budgetary constraints, but it’s hard to fault someone working outside the system to create a story that same system rejects as a matter of principle. While the bones call to mind a palatably mainstream plot, the details are far from conventional. This is a welcome reality and a selling point to usurp kneejerk disappointment in technical shortcomings. It can also get a little too esoteric at times, but that’s part of the charm. I only wish there were more visual flourishes like a memorably creepy image of McClarnon as winged witch turned owl because it brought the same sort of fantastical aesthetic as the voiceover. Perhaps it would only overshadow the message and ultimately prove exploitative to Native American iconography, but that two-second blink was chilling enough to risk more.

Because its storytelling process embraces dialogue-heavy scenes and introspective close-ups portraying its emotional trajectory without huge fanfare beyond expressive performances, I’d be remiss to not mention Rondeaux’s authentic turn as Mekko. A former professional on the Rodeo circuit turned stuntman in Hollywood westerns; this horse-training cowboy earns his chance to shoulder a film. He’s as effective as the shy, blushing stranger quietly speaking with Podemski over a slice of pie as he is the stern, biting authoritarian laying down the truth for the McClarnon’s punk. Rondeaux has an air of regality to him that only wavers when the frustration and pain of his family and friends’ fates boils to the surface. But even then we find ourselves condoning his actions. After all, his grandmother said he could save people. Perhaps she was right.

Mekko makes its International premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 13th.