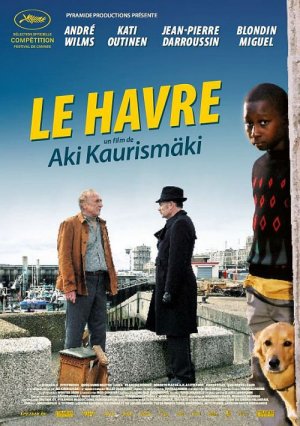

According to André Wilms—the star of Le Havre—during his hilarious stream of consciousness Q&A at a screening for the Toronto International Film Festival, director Aki Kaurismäki decided it was time to make a comedy/fairy tale. The Finn had created so many “desperate” films that a change was needed. And what better setting than France to bring it to life, a country who’s film history is held dear and apparently seen as dead by the director, (sentiments Wilms agreed with only half-jokingly). You’ll notice subtle nods to an older style with a lingering camera, exaggerated acting, and theatrical vibe, but that’s not to say the film itself is old fashioned. No, the color is vibrant, the characters humorous—if not overtly so—and the hard-boiled noir is subverted just enough to keep the whole light and airy.

It is Wilms’ Marcel Marx who we meet in the beginning. A complicated man with a penchant for doing the wrong thing, his shoe shiner cares for little else than a drink and his wife. Treading up and down Le Havre for heavily trafficked spots that won’t call the police on him for loitering, Marx sticks to the train station and street corners to ply his craft with comrade Chang (Quoc Dung Nguyen). Unafraid to polish the loafers of a shady man handcuffed to a briefcase, he isn’t one to gloss over the fact that getting paid means more than the life of his customers. Besides his proclivities for alcohol and letting his wife Arletty (Kati Outinen) hoard the rest, though, that money rarely sees the light of day. Instead, Marx enjoys walking into the establishment of friends—Yvette’s (Evelyne Didi) bakery and François Monnié’s grocery—to take at will with a friendly smile and unspoken I.O.U. in return.

Once we step back and take a good look at his life, we sense the karmic forces afflicting him. Shady in his work and forever stopping at the bar while his wife dutifully cooks dinner, it’s no surprise that his situation is impoverished. And the hard knocks keep coming with Inspector Monet (Jean-Pierre Darroussin) on his tail and Arletty soon forced to go to the hospital with a grave illness. But when faced with an opportunity for redemption, somehow Marx takes the high road. How he goes about helping a young refugee, escaped from a smuggled boat canister accidentally left at port, may not be legal but does show his heart is in the right place for once. With the city’s police chasing the child, Marx decides to hide him in his now empty house. Idrissa’s (Blondin Miguel) polite and mannered stowaway becomes a part of the street and a reason for Yvette and the grocer to open their doors to a man they’d locked out only yesterday. For once Marx was being selfless.

Le Havre is very matter-of-fact and almost mechanical in its orchestration with stoic characters in a hyper-real setting. Each actor is often held in frame with a motionless face of sad dejection—his or her mannerisms bordering on the broadness of silent film. Such an aesthetic lends itself to the wispy comedy of mostly straight-faced retorts, the most static of which comes from Outinen’s wonderfully quiet performance. Wilms is much more nuanced than his bombastic real life persona, but just as funny with the situational quips Kaurismäki sprinkles throughout. His very involvement with Idrissa appears like it should be out of character and yet remains natural. Unable to come home to his doting wife’s love while she’s in the hospital leaves a void in his day-to-day. Filling it with a mission to reunite a young boy with his mother already in London may be unconventional, but it works to turn his luck around and find a neighborhood’s respect.

Shot by only doing two takes each go in front of the camera, Wilms’ remarks about his director’s exacting process and ‘less is more’ philosophy are easy to believe. Even as the story follows Marx on his new quest—the fruits of which lead to an ending so over-the-top you have to applaud the filmmaker’s unabashed fervor to end on a happy note—no one is wasted as everyone gets an opportunity to shine. Supporting players like Didi and Monnié are fun on the periphery and Nguyen is great with his deadpan delivery and general subservience to the shoe shiner that took him under wing. A mini subplot featuring an aging rocker and his wife is also cute, its inclusion a throw-in to help easily fill the plot hole of a lack of funds to send Idrissa away. The love between Roberto Piazza’s Little Bob and Myriam Piazza’s Mimie is endearing and schmaltzy, but the payoff rock number by the band is a welcome interlude to experience.

As far as Wilms goes, I may be remembering the real man’s frank explanation of his hangover and inability to talk with any sense too much. Whether I am or not, I still will hold strong to the fact his performance is a great piece of comedy completed with a nuanced sweetness that’s unexpected at the start. The best piece of the puzzle, though, is an honor split between Darroussin and Miguel who both excel in crucial roles. We follow the character of Monet as he hunts the boy, watch as his history with the city is exposed when entering Claire’s (Elina Salo) bar, and enjoy his serious demeanor touched with a hint of tenderness. And Miguel—well this young boy steals scenes with his robotic maneuverings. A kid who Wilms admits is the perfect actor for Kaurismäki’s obsessive precision, you do care about his plight through his blank stares of silence. It’s okay too that part of wanting him to escape is to allow Marx a well-earned success in a life short on them. Sometimes we all need a happy ending and Le Havre doesn’t disappoint.