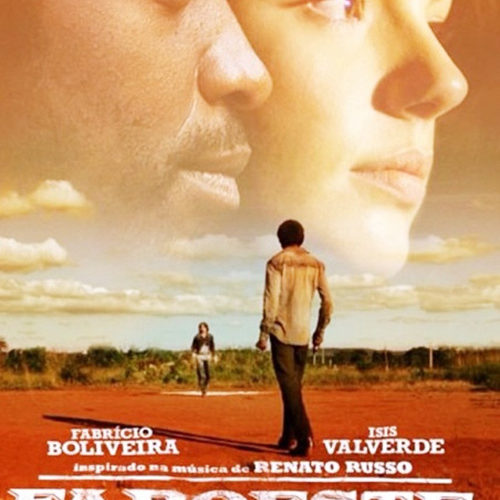

Composed by Renato Russo in 1979 and finally released in 1987 on his band Legião Urbana’s album Que País É Este, “Faroeste Caboclo” became a folk song hit in Brazil. It was Russo’s family —Renato died in 1996 due to complications from AIDS—who began the process of finding the right talent to adapt its nine-minute story of João de Santo Cristo for the big screen ten years after his death. A few delays later—including an attempt to stall production due to outside copyright interests—filming began under the watchful eye of director René Sampiao within a recreation of the song’s 70s-80s Ceilândia, Distrito Federal locale. It’s a ruthlessly violent modern-day Romeo and Juliet tale of romance and redemption with João’s (Fabrício Boliveira) inevitable end foreshadowed in its very first scene.

Written by Victor Atherino and Marcos Bernstein, Brazilian Western wastes no time showing its antihero’s unflinching ability to kill at age fifteen. We glimpse memories to help explain the origins of his temper and bloodlust through flashbacks cropping up during the course of the film, understanding his fearless, nothing-to-lose attitude in the process. The crime gets him fifteen years in a correctional facility—time that only hardened his stone-faced demeanor. He does want to change, though, deciding to hitch a bus to find the last living member of his family: a cousin named Pablo (César Troncoso). A gangster looking to make drug headway in Brasília’s club culture, Pablo fixes João up with a carpenter knowing it won’t be long before the ex-con to seeks something with a higher pay scale.

What no one could have anticipated, though, was that his first drug deal would not only put him in the crosshairs of corrupt cop Marco Aurélio (Antonio Calloni) and therefore Pablo’s chief competition (Felipe Abib’s Jeremias), but also onto the path of a beautiful architecture student named Maria Lúcia (Isis Valverde). She’s the kind of woman who’ll make anyone do whatever’s necessary to keep her by his side, a fact made true by João’s willingness to give up the field of marijuana he plows for his cousin and become a full-time carpenter. Never meant to have his life be so simple, though, the realization he’d eventually need to overcome his thug persona to introduce himself to Maria’s Senator father (Marcos Paulo) proves the least of his worries once Jeremias gets his hands on him.

Similar to all gangster flicks, João finds himself enjoying the easy money as long as his girl doesn’t find out. With one of the best lines of the film, however, he realizes that the truth sometimes needs to be told before it’s discovered. Unfortunately for him that knowledge comes too late. But he’s willing to give it all up for her and saying so isn’t simply a sweet nothing to deflect his doing it anyway—her love is all that matters. Like every decision in his life, his retirement is a step behind as Jeremias and Aurélio drag him back full-force anyway. Following suit with João’s windowsill meeting of Maria comes a sacrificed Mercutio as well as the Romeo versus Tybalt standoff we’ve waited for since its tease at the start.

Sampaio deftly shifts time with the seamless flashbacks narrated by Boliveira, carefully sharing the details from João’s past that prove relevant to the present. His first kill sets the tone for everything coming after, making it so we assume the worst whenever he’s found with a gun in his hand and a body to shoot. But his love for Maria Lúcia soon sheds light on the reality of who he’s killed and why with new, emotionally harrowing moments projected when he’s most conflicted as to his next step. João has a code of honor where justified murder is just that—a deed to be performed and forgotten while life carries on in its aftermath. As the turf war between Pablo and Jeremias accelerates, though, the story they inhabit grows darker and more dangerous.

What João is forced to endure is a steady stream of bad luck and abuse that makes death seem a gift in comparison. Racism runs rampant whether it’s with the rival drug suppliers, Maria’s affluent parentage, or the regular citizens walking the streets. Being black has always put him at a disadvantage his street smarts generally overcome with a some help from his friends, but not even that experience can prepare him for the wrath of a jealous enemy in both love and career. There’s only one thing more threatening and volatile than a man (Jeremias) scorned by watching another (João) easily live the life he wanted but could never have, though, and that’s latter when he’s left broken by the former’s envious antagonist taking it all away with brutal force.

As a Greek tragedy, each player has his/her specific role to propel the plot onward towards its solemn climax. Therefore no one is necessarily more than their surface appearance, whether the obliviously bigoted father, loyal criminal, crooked cop, delusional psycho villain, or the many helpers on either side. But Valverde’s Maria and Boliveira’s João do take their roles further thanks to them being our protagonists and hopeful lovers. We assume she’s a one-dimensional damsel doing everything possible for her man until we learn how critical a role she plays in his suffering and the guilt harbored as a result while his constant struggle between light and dark has him effortlessly balancing fearsome and sympathetic. We need them to prevail despite their lives’ horrific turns, but not all love stories can be fairy tales.

Brazilian Western played at the Toronto International Film Festival. One can click below for our complete coverage and see the trailer above.