The Power, Corinna Faith’s haunted hospital creeper, hinges on such a richly atmospheric historical context that it’s a wonder it hasn’t been used as the backdrop for more horror. Set in 1974 London, the action takes place during a period known as The Three-Day Week––a time when the government-mandated power outages (and imposed other restrictions) to combat the lack of resources caused by widespread mine strikes. Faith’s film leverages both the physical realities of these blackouts and the class-based anger of the moment for maximum effect. It eventually resorts to well-intentioned but inelegant info dumps to reach its climax, but the tactile environments and direct filmmaking separates it from most films of its ilk.

The story centers around Valerie (Rose Williams), a first day nurse who’s been having nightmares related to an unclear trauma, and has a comically unlucky fear of the dark. Raised in an orphanage, she sees the hospital as a possible community. But her idealism cracks in the face of the shrewd Matron (Diveen Henry), who first denies her request to work in pediatrics, and later, sentences her to the night shift for disobeying her rules. In this case, that infraction is as minor as Val talking with Franklyn (Charlie Carrick), a kindly doctor, despite Matron’s insistence that nurses should not talk to doctors.

There’s a visible pecking order in the hospital as nurses wait for doctors to administer the “real” care and are forbidden from answering any patient’s questions that could counter a doctor’s opinion. Faith’s film is especially effective in communicating this oppressive working texture while also suggesting an unchallenged, toxic living history to the hospital. And compared to the icy or apathetic demeanor of the rest of the staff, Val has an outlying warmth with patients including Saba (Shakira Rahman), a young girl of unspecified descent who’s subject to casual racism because of her tendency to speak in her own native language when afraid.

Seen as a troublemaker by other staff members for her skittish nature caused by her own fear of the dark, Val empathizes with her based on their shared phobia. Those unpleasant coworkers pale in comparison to Neville (Theo Barklem-Biggs), a scuzzy and egotistical night guard who believes he deserves more than a “thank you,” and Barbara (Emma Rigby), a veteran nurse who Val has a personal connection with.

Far before the lights go out, every inch of the hospital is aglow with dread; Val’s movements and interactions pulse with an unease. Production designer Francesca Massariol hits all the requisite hallmarks of a haunted place with not only hilariously ominous wall murals but the metallic discomfort of a period-era hospital.

Amplifying that restless aura is Elizabeth Bernholz aka Gazelle Twin and Max de Wardener’s excellent score––a soundscape of treated found-sounds, brittle synth programming, and Bernholz’s abrasively mutant voice modulation. Their score is smartly paced with the ramping intensity of the film as their churning synths meld with the sound design team’s foley work of squelching hallways pipes and the heavy ambient breathing from an intensive care room where the majority of the film takes place.

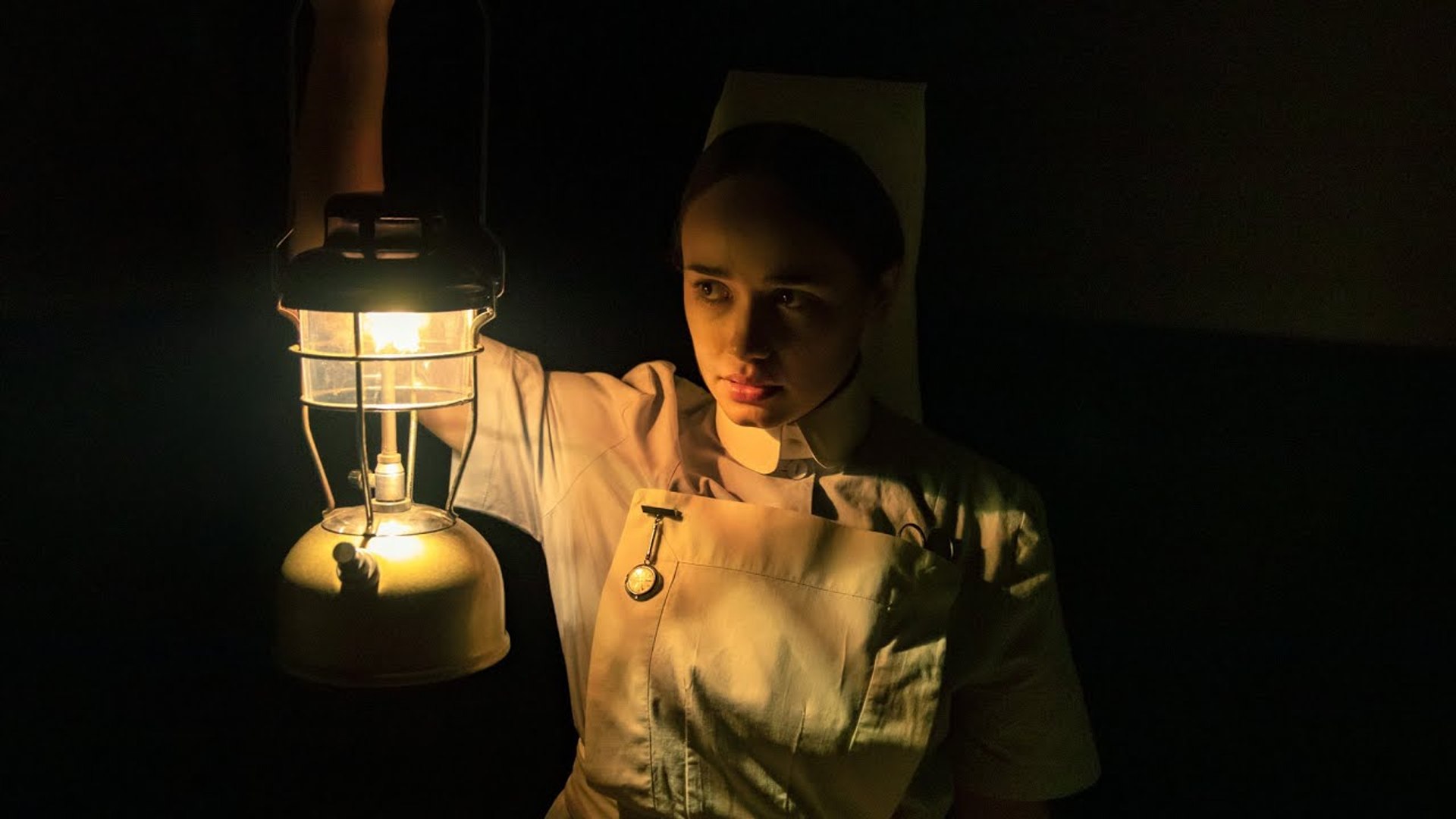

The Power is at its strongest in these moments of alienation and lucid distress. And once Laura Bellingham’s crisp, shadowy cinematography and Faith’s precise camerawork take center stage, the sense of suggestion calcifies into a palpable terror that doesn’t feel artificial or cheap. Their collaborative vision of the dark is inky but drawn to pools of light and reflective surfaces revealed through a held lantern. When violence erupts, they can come from unseen angles––but they’re refreshingly always fully coherent. There’s none of the usual viewer rhetorical questions about “what happened to so-and-so there” that sometimes plague low to mid-budget horror films that rely on darkness. The unreliability of the story here is entirely sculpted for better or for worse.

In the lead role, Williams has a tough performance as a meek presence whose arc follows an evolving sense of control. That’s an internal and external change in agency and physicality and she mostly pulls it off even as the plot corners her into some places that require jumps or an overly guiding hand. Without any further elaboration, the thematic connections between the hospital and Val’s story are foundational to the plot in a way that at first feels satisfyingly blunt, but threatens to reach into redundancy by the end of the film.

It’s not the wrong finale as much as one that’s disappointingly awkward in its execution. Theoretically, the primal scream of an ending is right. It reiterates the key thesis, intersects every strand of the plot, and offers catharsis. But, in a film whose mood comes so intuitively and allegorical content otherwise feels so clear, maybe The Power should have still left a few things in the dark.

The Power is now on Shudder.