For our most comprehensive year-end feature we’re providing a cumulative look at The Film Stage’s favorite films of 2023. We’ve asked contributors to compile ten-best lists with five honorable mentions––some of those personal selections will be shared in coming weeks––and from tallied votes has this top 50 been assembled.

Without further ado, check out our rundown of 2023 below, our ongoing year-end coverage here (including where to watch many of the below picks, both on streaming and in theaters), and return in the coming weeks as we look towards 2024.

50. Sick of Myself (Kristoffer Borgli)

Kristoffer Borgli’s first Norwegian feature is a work of disgusting, hilarious, horrifying genius. Signe (played brilliantly by Kristine Kujath Thorp) is an early-20s narcissist who, galled by the success of her equally self-centered boyfriend, spirals into full-on Munchausen syndrome. As timely as it is hard to watch, Sick of Myself doesn’t just push boundaries; it vomits blood all over them. Signe would be thrilled to know she cracked this list, and it’s darkly, delightfully fitting that she scraped into last place. – Lena W.

49. After Love (Aleem Khan)

After Love is a story of the past returning to haunt. First, because the heart-crushing 2020 feature netted several nominations and a deserved best actress win for Joanna Scanlan at the 75th BAFTA awards but only made its way to a U.S. release at the start of 2023. Second, and most importantly, because it’s about a widow who discovers her husband has a secret family in another country and must now excavate the happy lie of her marriage. I promise you, though, it’s not nearly that simple. Mary Hussain (Scanlan), an aging white English woman, sacrificed all that she knew to convert to Islam in her early 20s so she could marry a Pakistani-born Dover ferry captain. Upon his death, she finds out he never expected the same of his brittle French mistress, Genevieve (Nathalie Richard), with whom he shared an entire world in Calais. Mary ventures to France to confront the woman, is mistaken for a housecleaner by her, and then uses this cover to investigate the home her beloved husband shared with a woman who couldn’t be more physically or emotionally different. All the while, Genevieve is waiting for her son’s father to come home. Khan’s images are quiet and raw, every shot a novel unto itself. I sobbed all the way through. – Robyn B.

48. Walk Up (Hong Sangsoo)

After the overwhelmingly direct nature of its predecessor, Hong Sangsoo’s Walk Up feels like a particularly low-key yet beguiling reconfiguration for the master of unpredictability and repetition. Marrying architectural and (narrative) structural conceit, Hong infuses this stable space with a profound melancholy, taking stock of the way one lives life with a haunted foreboding unlike anything else in his filmography. By the time of the final, stunning gambit, it is clear that his “infinite worlds possible” are as mysterious and generative as ever. – Ryan S.

47. Hello Dankness (Soda Jerk)

The 2016 U.S. Presidential election was full of psychotropic angst that left Americans frantic over their country’s fate. The hysteria of these events distilled people’s comprehension of the world and divided a nation. Rogue samplers Soda Jerk crafted Hello Dankness, an all-archival, political fable that centers on the search for secured destiny amidst a deal-breaking outcome, through rotoscoping certain portions of past media to reflect Trump and Clinton devotees. Soda Jerk up the ante by making it a stoner musical and having soundbites dubbing characters, igniting a humorous, jaw-dropping nostalgia that resonates with voters. – Edward F.

46. Beau Is Afraid (Ari Aster)

Ari Aster’s gift may ultimately be making a 2005 sensibility work: between twee performance-art-kid interludes, Adult Swim humor, and a general mean-spiritedness, you get the sense of someone stuck in their formative film-school years. Maybe Beau is Afraid shouldn’t work, but the pain at its center is very real––as anyone who has a strained relationship (to say the least) with their mother can recognize. Maybe consider yourself blessed that you didn’t understand. – Ethan V.

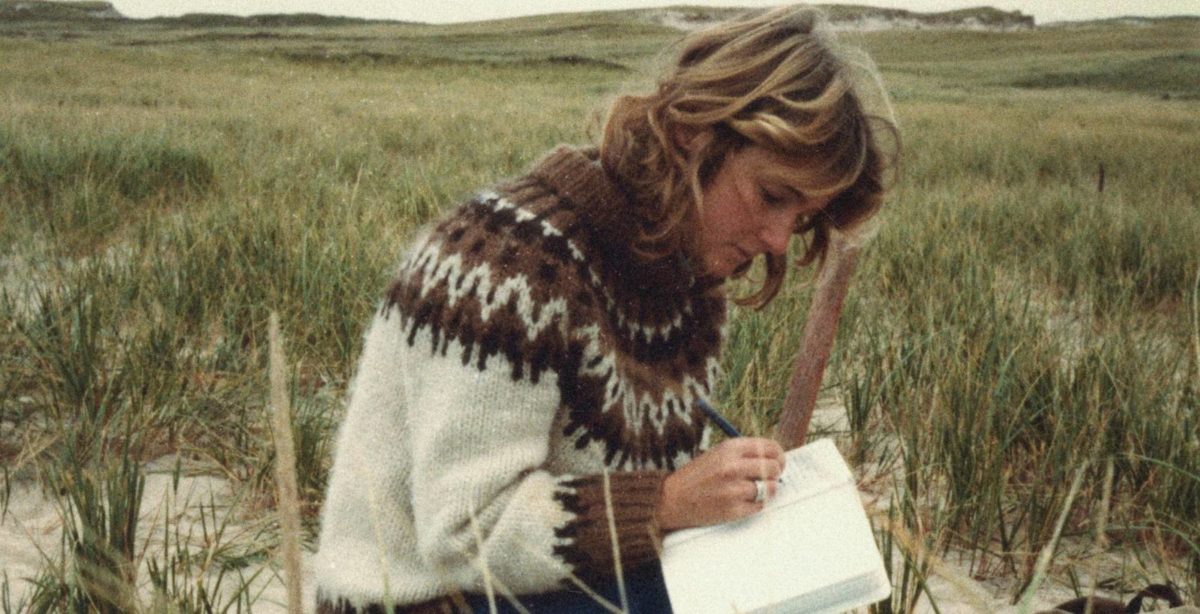

45. Geographies of Solitude (Jacquelyn Mills)

What makes Geographies of Solitude so special is how it plays with the interactions between its subject matter, Zoe Lucas––a researcher who has lived for over 40 years on Sable Island––and the director, Jacquelyn Mills. At times we hear snippets of their conversations; at others we just see the camera follow Zoe around, considering and addressing the presence of Jacquelyn behind it. The film preciously balances Zoe’s fascination with her findings (which includes a collection of literal trash that shores up on the isle) alongside the director’s visual and aural experiments. They’re both working with the same materials and communicate with each other from their particular fields, creating a fascinating experience of a singular place. – Jaime G.

44. The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (William Friedkin)

The final feature of legendary filmmaker William Friedkin, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial sent him out on a high. Remarkably bold in its formal and aesthetic approach, the courtroom drama is practically Bressonian in its minimalism and removal from conventional cinematic attributes. Almost the entire picture comprises tight shots on actors (including one final riveting performance from the late Lance Reddick), fewer than ten contained in this one setting where a series of witnesses are called to sit in a chair and be grilled by opposing lawyers. We are in this room for these two hours and that’s it. We see it all unfold, and it’s up to us to make interpretations or judgments, if we wish, as to who these people really are. It’s absolutely gripping cinema. – Mitchell B.

43. Unrest (Cyril Schäublin)

Set in the beautiful mountain town of Jura, Switzerland, circa 1872, Unrest traces the tension between a band of anarchists and the industrial capitalism that drives the town’s watchmaking industry. Here a romance brews between anarchist cartographer Pyotr and a factory worker (stunning non-professional Clara Gostynski) responsible for crafting the titular unrest watch movement. Unrest’s ideals are undeniably political, but they unfold in a sly, playful manner. Absent any didacticism or preachiness, Unrest is more fairy tale than political screed, and the ultimate effect is more satisfying as a result. – Caleb H.

42. The Human Surge 3 (Eduardo Williams)

It’s been seven years since Eduardo Williams’ The Human Surge premiered, and with this threequel he takes many of the concepts and themes from the original––globalization, rapidly changing technology, and how young people adapt to our ever-changing world––and blows them up to a scale that is literally too big to fit onscreen. Shot on a 360-degree camera, edited with a VR headset, then flattened and distorted into a widescreen aspect ratio, Williams creates a porous, wholly original vision of a world where physical and figurative boundaries vanish. The experience is nothing short of exhilarating. – C.J. P.

41. Knock at the Cabin (M. Night Shyamalan)

Everything that makes The Village my favorite M. Night Shyamalan film exists within Knock at the Cabin, his adaptation of Paul Tremblay’s novel. Impeccable blocking allows his shallow focus and camera pans to build suspense while his extreme close-ups supply the emotional weight shouldered by each character once their love proves humanity’s last hope for survival amidst a world mired in hate. Ben Aldridge and Jonathan Groff bring us into their hearts even as they try steeling themselves to what becomes increasingly true in their minds, but it’s Dave Bautista who astounds with an achingly beautiful empathy made purer by the incongruity of his physical stature. And despite my usual inclination towards open-ended interpretation, the potency of this tightly wound morality tale hinges on its definitive answers. Providing them isn’t a cop-out or twist––it’s quite literally the point. – Jared M.

40. Hit Man (Richard Linklater)

It’s Richard Linklater’s screwball-noir about a New Orleans University philosophy professor who moonlights as a fake hitman only to find love and a better version of himself––and it’s as just good as that sounds, along with a nice nudge to the A-list for perennial charmer Glen Powell. Linklater explicitly lays out some of his biggest themes and concerns during the lecture sequences, but he’s masterful in the climactic moments that are so absurdly tense that one can only laugh in response. See it with the biggest audience possible. – Zach L.

39. Perfect Days (Wim Wenders)

Every work day, Hirayama (Koji Yakusho) wakes, waters his plants, washes up, dresses in his coveralls, and leaves his house before the sun fully rises. He buys a coffee can from the vending machine next door and hops in his van, which is filled to the brim with cleaning products. Before turning on his vehicle and going to the various public toilets in Tokyo he thoroughly, he puts a tape in the cassette player. The Animals, Patti Smith, the Velvet Underground fill the air as we witness Hirayama’s Perfect Days. Maybe the best representation of “mono no aware” this decade so far. – Jaime G.

38. Bottoms (Emma Seligman)

Since Beau Is Afraid and Poor Things also feature on this list, it would be audacious to call Bottoms the best weird, horny movie of 2023. But if Emma Seligman’s raunchy teen comedy has one thing, it is audacity. To center on two problematic lesbian virgins. To time an explosion to “Total Eclipse of the Heart.” To put a janky wig on Ruby Cruz and somehow make it hot. To crack (actually funny!) rape jokes. Bottoms is the best manifestation of adolescent wish-fulfillment, a divine gift to sapphics who learned to love movies by watching Scott Pilgrim vs. the World and Jennifer’s Body. We, the Girls Who Get It, can only say thank you. – Lena W.

37. The Iron Claw (Sean Durkin)

A knockout gut-punch off the ropes, The Iron Claw traces the devastating true story of the Von Erich family, a 1980s Texas wrestling dynasty comprising several brothers whose deep talents in the ring eventually collapsed under the weight of their exploitative, domineering father (Holt McCallany). As the eldest sibling, Kevin, Zac Efron turns in a transformative performance, navigating Sean Durkin’s visceral and intimate American fable with a roided-out musculature––all while trying to ward off a family curse of personal catastrophe. “If we were the toughest, the strongest, nothing could ever hurt us,” Kevin remembers his father telling him. But outside the ring, that philosophy became a death sentence of tragic proportion. – Jake K-S.

36. Samsara (Lois Patiño)

“The world opens to those who open up to it,” a character prophesies early into Lois Patiño’s Samsara, and for a film designed to rejig your bearings, the way you respond to the things around you, the words amount to a mission statement. Virtually every frame here bristles with a hallucinatory static––fitting for a story that charts a soul’s journey through different states of being and different bodies. Long, long before Samsara asks you to close your eyes and join Patiño on a journey across the Bardo, catapulting you from the lush rainforests of Laos to the beaches of Zanzibar, the film arrives at a kind of transcendence. Apichatpong Weerasethakul hovers above many a shot, but the disquiet is Patiño’s own making, and so is the sense of wonder. Samsara unspools as a Heraclitean river: you cannot step into it twice, for it is not the same film and you are no longer the same person. – Leo G.

35. Godland (Hlynur Pálmason)

The first half of Godland paints a beautiful-yet-terrifying vision of late-19th-century Iceland as an unforgiving landscape primed to swallow up anyone who displays the smallest weakness or lack of respect. The second half shows that humans pose the same threat to any outsider appearing with those deficiencies. Young Lutheran priest Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove) never stood a chance, his fate written long before he accepted the task to bring the gospel here from neighboring Denmark. In Godland, the dangers of nature and men are distractions though from the true threat, which is always an internal one. “Pride goeth before a fall,” the proverb reads, something the arrogant Lucas might’ve realized had he taken the time to open his Bible. – Caleb H.

34. Our Body (Claire Simon)

It was tempting, sitting in a dark room watching Claire Simon’s Our Body, to point at the screen and identify all that was happening––every ailment, every issue, every miracle as she takes us inside an OB-GYN ward at a Parisian hospital. Identification, however, is not the point; relatability is not the point. Rather, in a time of medical impersonality, Simon shows us the humanhood of patients and doctors, caretakers and spouses. You can think you know someone by a diagnosis. Simon shows us so much more. – Fran H.

33. How to Blow Up a Pipeline (Daniel Goldhaber)

Fifteen months after declaring it my favorite of TIFF 2022, How to Blow Up a Pipeline remains one of the best of 2023. An inspired adaptation of Andreas Malm’s non-fiction, book-form argument criticizing today’s pacifistic climate activism by declaring sabotage its “logical” and necessary evolution, director Daniel Goldhaber and co-writers Ariela Barer (who also stars) and Jordan Sjol craft a heist thriller depicting a band of amateur revolutionaries who are determined to give his words life. It’s a tense, often-funny, and exhilarating single-day roller coaster ride utilizing meticulously planned flashbacks to simultaneously deliver exposition and ignite mystery. Yet nothing I say will prove a superior pitch than both the US and Canadian governments issuing warnings that the film might potentially inspire real-life terrorist attacks by radicalizing its audience. That, my friends, is the fearsome power of great art in action. – Jared M.

32. Trenque Lauquen (Laura Citarella)

Strange business is afoot in the Argentinian town of Trenque Lauquen. A hidden love letter uncovers a decades-old mystery and a terrifying, amphibian monster is on the loose. A searching young woman must put the pieces together and solve this unlikely, baffling charade. Laura Citarella accomplishes the impossible in her much-acclaimed masterpiece: she not only pulls off a creature feature on a shoe-string budget, but combines it with a Nicholas Sparks romance over four engrossing hours. In doing so, Citarella also ably demonstrates that, humble means notwithstanding, what stands between filmmakers and greatness is only directorial imagination. – Ankit J.

31. The Plains (David Easteal)

Perhaps the greatest gift a film can give its audience in today’s day and age is patience. The gift of time. The opportunity to take a breath and look intently, curiously at what is happening onscreen. Not many will heed the word, but David Easteal’s The Plains is a marvelously structured road narrative that offers the opportunity to take in the idea of time as an inseparable part of the film experience. When the commotion is kept at bay, we get to really hear the words of the actors, see what’s happening at the periphery of frames, and take in the ways people’s lives can drastically change in the small moments. – Soham G.

30. The Delinquents (Rodrigo Moreno)

The best kind of storytelling is both surprising as it unfolds and, when it’s over, you can’t imagine things having gone any other way. Moreno’s odyssey of a film explores moral dilemmas following a bank heist, only to morph into an Allen-esque tale of coincidence and romance before reaching a contemplative, poignantly open-ended conclusion. Carried by a diptych of matching performances from Esteban Bigliardi and Daniel Elías, it’s rich, expansive, filled with tonal shifts and narrative twists so unexpected yet jazzily organic they remind you of nothing less than life itself. Mesmerizing. – Zhuo-Ning Su

29. Here (Bas Devos)

Aptly billed “the year’s most benevolent film” by Rory O’Connor in his Berlinale review, Here is a work of contagious humanism, a film that feels almost subversive in its refusal to be powered by external conflict and three-act narratives. This is cinema at its kindest: filming once again in Brussels, writer-director Bas Devos trains his camera on the city’s underexposed and underrepresented without reducing them to victims or vacuous mouthpieces. Its meandering plot, loosely tethered to the perambulations of a Romanian construction worker on his way home for the summer holidays, is the stuff of dreams: a sequence of largely nocturnal encounters with friends and strangers sharing memories over soup. Here is many things––food porn, a romance, a lecture in bryology. It is also a migration story, palpably attuned to the alienation of its deracinated characters and yet unwilling to articulate it fully––a restraint that makes it all the more evocative and perceptive. – Leo G.

28. The Beast (Bertrand Bonello)

Bertrand Bonello’s speculative reinterpretation of a classic Henry James haunter presents a sci-fi universe without fancy gadgetry or dystopia-chic architecture. Instead this future world is a Gothic one, unable to escape its past or its fate––truly “wyrd” in the Old English sense. Here’s a genuinely transgressive film of floods, incels, trash humpers, murder, green screens, and club music without a single marketable hook; it’s a miracle movies like this are still made. – Zach L.

27. All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt (Raven Jackson)

A film that feels uprooted from deep beneath the earth, Raven Jackson’s poetic, patient debut is a distillation of cinema to its purest form, a stunning patchwork of experience and memory. Tethered around the life of Mack, a Black woman from Mississippi, as we witness glimpses of her childhood, teenage years, and beyond, All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt becomes a sensory experience unlike anything else this year. Shot in beautiful 35mm by Jomo Fray and edited by Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s collaborator Lee Chatametikool, there’s a reverence for nature and joy for human connection that seems all too rarified in today’s landscape of American filmmaking. – Jordan R.

26. The Taste of Things (Trần Anh Hùng)

At the start of Trần Anh Hùng’s French-language romance The Taste of Things, a balleting camera whirls through a state-of-the-art 1890s French countryside kitchen as Eugénie (Juliette Binoche), Dodin (Benoît Magimel), and two young female laborers work in rapid, precise movements to produce a decadent feast. For minutes on end, the artists and their helpers utilize complex, well-worn techniques to scoop perfectly oval seafood quenelles, roast a rack of veal dripping succulent fat, and whip shiny meringue for baked Alaska. (Or, as the film describes the dessert, “a Norwegian omelet.”) Dodin is a famous chef and restauranteur, Eugénie his personal cook and the love of his life. Through decades of working together and finding equilibrium as creative partners, they have fallen in ever-lustful love, but Eugénie has no interest in giving up her freedom to marry him. That Binoche and Magimel share powerful but comfortable chemistry should be no surprise: the actors have an adult daughter from a relationship that ended 20 years ago. Jonathan Ricquebourg’s dynamic cinematography, however, is just as formidable as their onscreen passion. – Robyn B.

25. Youth (Spring) (Wang Bing)

The most claustrophobic and challenging entry in this list has found itself in the top half, indicating that Wang’s commitment to immersion and the attention buy-in he asks of viewers has very much paid off. In this first of a putative trilogy on contemporary Chinese labor––and a follow-up in mode to West of the Tracks, his most canonical work––Wang uses a three-and-a-half hour runtime and gradual, ultimately dizzying accretion of detail to show us exactly what the country’s new prosperity is built upon: entire cities of full of young seasonal workers who, in an optimistic note, could use their position in the pecking order to ultimately uplift themselves. – David K.

24. Do Not Expect Too Much of the End of the World (Radu Jude)

If 2022 was defined by the toothless “eat the rich” satire, 2023 countered with substantive takedowns of gig economy culture. David Fincher’s sardonic Killer commanded the most attention in this regard, showing that even hitmen are at the mercy of late capitalism’s whims, but it was Radu Jude’s latest skewering of post-pandemic life that took no prisoners. His nearly three-hour odyssey across Bucharest contrasted the daily routine of production assistant Angela (Ilinca Manolache) with the taxi-driving heroine of a 1981 Romanian film, showing how even sanitized working conditions in the movies have been drastically transformed by corporations that overwork and underpay. There can be no catharsis until workers’ rights are strengthened––until then, the only thing that will keep us sane is making stupid TikTok videos and laughing through the pain. – Alistair R.

23. Poor Things (Yorgos Lanthimos)

Yorgos Lantimos’ delirious adaptation of Alasdair Gray’s novel, dubbed the feminist answer to Frankenstein, confirms him as the 21st century’s heir to Buñel, juggling the sexual and the political, the surreal and the profound. Emma Stone is a beguiling, magnetic presence as Bella Baxter, whose sexual awakening prompts an undeclared revolt against a society too eager to put women in their place. Her primitive waltz with a top-form Mark Ruffalo is as shocking and erotic as anything onscreen this year. To quote Bella after a particularly steamy scene, “Why don’t people do this all the time?” – Ed F.

22. La Chimera (Alice Rohrwacher)

Where does cinema originate? I don’t mean apparatus or attractions. What I mean is: when we look around and watch, when does the air change? Cinema is alchemical. It cracks a statue’s neck and we’re the ones who break underground. It makes us a Eurydice of eyes, ghostly but full of want. Follow the thread. We owe it to cinema’s practitioners not to cry “magic!” at their labor and care. There is no magic here. She moved the camera. – Frank F.

21. Priscilla (Sofia Coppola)

After a couple of disappointments (which is to say “good” rather than great) in The Beguiled and On the Rocks, Sofia Coppola seemed, well, uninspired. Enter Priscilla Presley, who, knowing Coppola’s background––a child glued to one of the world’s most beloved men (albeit a more attentive one) and a woman who fell in love with a global rockstar (and Priscilla‘s composer, Thomas Mars)––came to Coppola with the story of her own life, telling the veteran writer-director she was the only one for the job. And boy was she right. Priscilla joins the company of Coppola’s best, further cementing her name among the greats. – Luke H.

20. Close Your Eyes (Víctor Erice)

Early into Close Your Eyes, an elderly film archivist remarks that his job is becoming more like an archeologist, and that sentiment carries throughout Víctor Erice’s masterful return to feature filmmaking after a three-decade hiatus. Set in 2012, the main story follows a director who begins a new search for the lead actor of his abandoned movie, who disappeared during shooting in 1992. That search delves into ideas around memory and identity that Erice elevates with meta elements, including the involvement of The Spirit of the Beehive lead Ana Torrent. But Erice’s film is at its most powerful in its melancholic look at cinema itself, which shows the medium gradually abandoning its history to evolve into something new. While many directors have spent the last several years waxing nostalgic about cinema’s past and power, Erice taps into the feeling of watching your passion move to the sidelines before fading into irrelevance. – C.J. P.

19. Passages (Ira Sachs)

I remain suspicious of “sex scenes good/bad” discourse. (What if every time we say the word “discourse,” we hear a squeak that means the exact opposite of cinema?) Obviously, there are deeply puritanical tracts running through our art. Obviously that art remains morphable pharmakon. Art reasserts incurious, prudish paradigms as often as it reorganizes horizons of want. To insist that the problem is only with seeing sex misses pleasure’s possibilities. Consider red silk robes, a dance floor of beats, a novel you might hate, another gin and tonic. The first audience screening. And then the sex scene––luxuriating, leg-aching, beyond meaning, mattering most. – Frank F.

18. De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor)

Oscillating between kaleidoscopic and jarringly banal, De Humani Corporis Fabrica calls back to experimental cinema’s long history with the contents of bodies. But even at their most compositionally abstract, veteran directors Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel are foremost documentarians. Compiled from over 350 hours of medical procedures captured at five different hospitals in France, the film juxtaposes stomach-churning surgeries and overheard ambient conversations about unpaid overtime into both a demystifying and amazing collage of modern science. – Michael S.

17. Ferrari (Michael Mann)

Appreciating Ferrari, Michael Mann’s long-planned biopic on the Italian racing mogul, it helps to go back to the director’s original rationale for the project. Where many viewers found an underpowered, stuttering work, the compressed period of time and the plot strands contained within were judiciously chosen by screenwriter Troy Kennedy Martin and Mann to highlight Ferrari’s imperious and, most importantly, monstrous capabilities. The climactic Mille Miglia sequence, more than any in Mann’s body of work, horrifyingly illustrates the cost of progress and profit motive’s denial of the human factor. And it being the first Mann film you could accurately call “operatic” since the ’90s only further enhanced what could be a dual directorial swan song with Heat 2, if it ends up being made. – David K.

16. Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros (Frederick Wiseman)

Part of the alchemy of Fredrick Wiseman’s Menus-Plaisirs – Les Troisgros, a four-hour feast, is that the necessary context and history of the family-owned Les Troisgros hospitality group isn’t quite known until the film is well into its third hour. A fascinating exploration of a three-star Michelin restaurant quite literally from farm to table, it explores the theatrics of the experience as well as the group’s supply chain. Wiseman, known as the poet of the staff meeting, captures the artistry of the group’s chefs, sommeliers, and suppliers in a decadent feast. Like a meal at Les Troisgros’ restaurants (and even their food truck) it’s a slow but meticulously crafted, immersive affair. – John F.

15. All of Us Strangers (Andrew Haigh)

There are many films about the devastating effects of the AIDS crisis, but very few that grapple with the loneliness of those left behind or came of age as it began to make headlines. Through supernatural metaphor, Andrew Haigh’s latest––and best––film tackles the existential displacement of a gay man (Andrew Scott) fast approaching middle age, his isolation only underlined by the near-abandoned tower block in which he lives. His friends have long moved out of the city, he has to maneuver a generational divide with a new, younger romantic partner (Paul Mescal) whose adolescence was far different to his, and he feels a longing to return to his childhood and come out to the parents who died before he became fully aware of his own identity. It’s a powerful, haunting film, one whose resonance comes entirely from its queerness; a faithful adaptation of the source material likely wouldn’t trouble many best-of-the-year lists. – Alistair R.

14. The Killer (David Fincher)

Despite the debate about how viable it is as autocritique for David Fincher, the pleasures of The Killer are simple. They come from its contrasts: a filmmaker known for his control designing a protagonist who has lost all his; a bad professional in a subgenre whose classics are about men of skill and composure; and a globetrotting backdrop marked by branding, anonymity, and computer-generated images you don’t quite know if you can trust. The result is the funniest movie of the year that’s also as taut as the leather glove in its opening image. – Shawn G.

13. The Boy and the Heron (Hayao Miyazaki)

A decade since his previous film and his initial retirement, Hayao Miyazaki returned with The Boy and the Heron, a major feat of animation that serves as both a capstone to a career and continued reckoning with how he passes the baton to further generations of filmmakers. The director remains fascinated by the ideas of creation, perfection, and violence that impacts multiple generations. Still, among a sea of themes, colors, and movement, Miyazaki keeps The Boy and the Heron grounded in emotional attachment, parental love, and the grief of a young boy making sense of the world around him. It’s another act of Miyazaki magic. – Michael F.

12. Past Lives (Celine Song)

The older you are, the more you will appreciate Past Lives. Sure, it’s about in-yun and reincarnation, but those are just code words for loss and remorse. Writer and director Celine Song captures the agony of dreams crushed, hopes thwarted, chances lost. Realizing you’re not what you thought you would be, that you will never get what you want, is at the heart of Past Lives. It’s a lesson missing from just about every other feature this year. – Daniel E.

11. Fallen Leaves (Aki Kaurismäki)

Throughout Aki Kaurismäki’s Fallen Leaves, the audience hears radio news updates on the Ukraine War. That devastatingly large-scale conflict adds an air of despair to the small-scale tensions at the heart of Fallen Leaves. The performances of Alma Pöysti as Ansa and Jussi Vatanen as Holappa are a perfect match for this mix of emotions. The characters’ lives are full of heartbreak and modest joys, resulting in an ending that feels both magical and refreshingly ordinary. Not every filmmaker can pull off that blend. Kaurismäki can, making Fallen Leaves a film to be treasured. – Chris S.

10. Anatomy of a Fall (Justine Triet)

2023 was the year of the courtroom drama (see #43 and parts of both #2 and #1), and Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or winner brought us into the specifically nutty circus of the French legal system, where a woman is put to the task of defending herself against accusations of murdering her husband. A riveting investigation occurs on the stand as she’s hounded by a supremely snarky prosecutor and the media puts her under the microscope, but what’s most fascinating about Anatomy of a Fall is its slow dissection into the anatomy of the marriage itself. Each scene uncovers new layers in their relationship, exploring the ways in which we all build up resentment, ache, jealousy and sometimes even rage over time. Were any of our spouses to perish under unusual circumstances, would we not also be the most glaring suspect? – Mitchell B.

9. The Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer)

In a media era increasingly shaped by immersive experiences, it’s hard to imagine another work as provocative, imaginative, and necessary as The Zone of Interest. Every Johnathan Glazer film arrives with the promise of glimpsing the artform’s creative frontier (Johnnie Burn and Mica Levi, take a bow), but the director’s first in a decade brought so much more. It was always going to stoke certain evergreen debates, but few could have expected it to hold such a mirror to our own doom-scrolling passivity. Martin Amis’ death falling within 24 hours of its Cannes premiere felt poignant. The timing of its eventual release has been another thing entirely. – Rory O.

8. Asteroid City (Wes Anderson)

Zip, boom, crash, bang––an alien arrives on Planet Earth and that’s nowhere close to the most shattering event in Wes Anderson’s latest, Asteroid City. A group of junior stargazers and their disaffected parents sit around the desert, processing (emotionally) and processing (scientifically) all that they do not know about each other and the world. Anderson rallies a troupe of regulars (Jason Schwartzman, wonderful, with his movie-son Jake Ryan, plus the brilliant Jeffrey Wright) and newcomers (Scarlett Johansson and Tom Hanks) to witness the universe cracking open. – Fran H.

7. Afire (Christian Petzold)

Christian Petzold’s Afire is a perfectly formed portrait of procrastination, narcissism, depression, and eroding self-worth. Following a frustrated writer who barely needs to be convinced the manuscript for his latest novel isn’t up to snuff, he heads to a seaside holiday home with a friend as all of his insecurities start to bubble up. Working in a Rohmerian register, with clear nods to The Green Ray, Petzold’s latest masterpiece humorously, then devastatingly depicts life’s frustrations through beautifully articulated performances from Thomas Schubert and Paula Beer. He’s emerging as one of the great directors of this young century. – Jordan R.

6. The Holdovers (Alexander Payne)

This film, in the best possible way, is a time machine. Comfortable, bittersweet, and very funny, it captures a moment that is nostalgic without the syrup. Paul Hunham––an embittered classics teacher at Barton Academy boarding school forced to spend his Christmas break babysitting abandoned students––is the pinnacle of Paul Giamatti’s incredible career. He’s mean, he’s pretentious, he’s pedantic. Yet he does care. He is in pain. Alexander Payne has softened as he’s aged, and that’s on full display here. The edge of the blade dulls, and we love these characters enough that we’re happy that they may make it through the day. Da’Vine Joy Randolph might give the best performance of the year and newcomer Dominic Sessa is a wonder. Nothing I write here will do the picture justice. Do yourself the favor and watch it. – Dan M.

5. Pacifiction (Albert Serra)

As is often the case, one of the year’s most compelling films comes in the form of one of its most unrelatable stories: the lonesome, lingering descent of a seasoned French diplomat stationed in Tahiti who slowly realizes how out of the loop his elusive higher-ups have left him. Spanish filmmaker Albert Serra is known for his singularity, and Pacifiction, his first feature set in the modern era, showcases that as much as his eclectic period pieces (e.g. Liberté, Story of My Death). Come for the most beautiful, glowingly hazy cinematography you’ve ever seen and get caught in the marble-blue waves of its hypnotically long takes and gulf of purpose. – Luke H.

4. Showing Up (Kelly Reichardt)

Throughout Kelly Reichardt’s latest perceptive portrait of disillusionment, a needy pigeon coos at Lizzy (Michelle Williams), a sculptor facing burnout and a nearing deadline. Alternating between Lizzy’s day job at her alma mater and free time in an ineffectual home workspace, Showing Up examines both imposter syndrome and living with the knowledge that those external and internal barriers won’t disappear. Things usually get done; you just might need to deal with that injured bird first. – Michael S.

3. May December (Todd Haynes)

A twisty, often hilarious film about the identities we construct and the performances we put on day after day, May December may take inspiration from the May Kay Letourneau story, but Todd Haynes and screenwriter Samy Burch are more interested in ways that life and art intersect and overlap. May December constantly reorders the audience’s sympathy, moving from Julianne Moore’s Gracie to Portman’s B-movie actress Elizabeth before finally settling on Charles Melton’s Joe, a man stuck in a type of arrested development. With a trio of standout performances, including a major discovery in Melton, May December not only ranks as one of the year’s best, but among Haynes’ finest films. – Christian G.

2. Oppenheimer (Christopher Nolan)

Several 2023 films share a desire to understand humanity’s worst tendencies through the eyes of perpetrators and the complicity that enables them. With Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan wields objectivity and subjectivity to unpack the motives behind innovating one of America’s greatest atrocities. It’s a portrait of brilliance choked by arrogance, naivete, and constant equivocation. Bringing these into conflict, Nolan avoids stodgy biopic form and instead traffics in backroom thriller––a once-in-a-generation experience yielding exhilaration and devastation. – Conor O.

1. Killers of the Flower Moon (Martin Scorsese)

“Inevitable” could summarize this placement. It’s hardly surprising or compelling to call this dense, dizzying, overwhelming film the year’s best. But I think it’s here less for any one success than because nobody’s able to agree exactly how or why it succeeds––if anything you’ll find admirers and skeptics sharing more than a few opinions, just a difference on the Rorschach’s ink pattern. All I might add is that I’ll never fully shake those final minutes, suitable as anything to remember 2023. – Nick N.