With the endless citations of Hitchcock’s “cattle” and Bresson’s “models,” there’s become more and more awareness of the troublesome tendency (one could even call crisis) within both criticism and cinephilia to overlook actors, especially so within the framework of a “formalist” director’s work. It’s as if there’s a lack of understanding of the simple and blatantly obvious fact that performance is a part of mise-en-scène, and that the expressive way an actor can move or speak is just as effective as any tricks of the trade.

Yet a difficult question arises when looking at how a movie star in particular fits within a director’s scheme. While some just point to them as necessary tools in funding an auteur’s passion project and move on from there, in the case of what are ostensibly star vehicles, simply ignoring their established personality is something of a fool’s errand. Thus, when bringing up the one and only Tom Cruise — who, in his multi-hyphenate position as actor and producer, we realistically have to admit implicates a degree of creative control — it becomes an unavoidable proposition.

To distil Cruise’s star-making breakthrough in the 1980s to two images (which in both cases obviously feature him donning killer shades), we think of him sliding down the hall in his undies to “Old Time Rock and Roll” in Risky Business or speeding on a motorcycle to “Danger Zone” in Top Gun. Cocky, pretty, and always impeccably dressed, Cruise in many ways acted as a response to the movie-stars of the ’80s: a boy-ish action hero standing in contrast to the physically imposing Schwarzenegger and Stallone, and a skilled, charismatic — if not chameleon-like — dramatic actor whose presence is reminiscent of method stalwarts De Niro and Hoffman. He was essentially perfect for the post-New Hollywood system, which had space for both the Bruckheimer / Simpson blockbuster and the comparatively more “adult,” talky legal thriller.

Continuing into the ’90s with a string of commercial and critical successes (A Few Good Men, The Firm, Interview With the Vampire) and the odd flop (you can’t remember Ron Howard’s 70mm period epic Far and Away for a reason), Cruise had cemented himself as the biggest movie-star in the world. His very own franchise was the logical next step. Enter Mission: Impossible.

For someone to shepherd his inevitable box-office juggernaut, instead of a Stephen Hopkins or Roger Spottiswoode to steamroll over, Cruise and his producing partner, Paula Wagner, picked Brian De Palma, who, despite having before balanced for-hire work (Scarface, The Untouchables), had never quite played in the blockbuster realm of his friends Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. A hard-R filmmaker, De Palma ran into his fair share of controversy throughout the ’80s and ’90s from critics and activists alike, thanks to his various “contemporary” updates of Alfred Hitchcock that reconfigured images from the master’s filmography into the realm of grisly slashers and erotic thrillers.

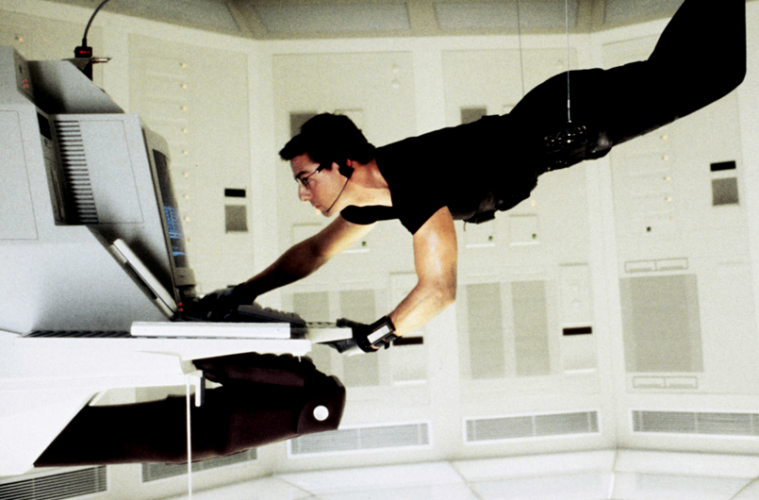

For not just trafficking in the de-sexualized PG-13 rating (the very first of his career) but also having the pressure of a tie-in N64 game, U2 song on the soundtrack, and likely soda / potato chip / fast food promotion of some sorts, the easy narrative would be to say the subversive artist of Hi, Mom! took a necessary paycheck gig coddling a star’s ego to bide time until his next passion project. Yet one locates in Mission: Impossible not a tension or subservience between director and star, but rather a synchronicity. Rather than subvert Cruise’s movie-star image, De Palma’s typically intense formalism situates him in his natural habitat.

De Palma is fully aware that Cruise is too big a star to really disappear into a role. He may don a latex face for portions of the film, but he never disguises his iconic voice. Simply put, Ethan Hunt is Tom Cruise: a perfectly poised image (some may say cipher) pirouetting around other perfect images of architecturally stunning European locales or fortress-like CIA headquarters.

In Cruise having his own James Bond, the film had to jettison the ensemble-based narrative of the original Mission: Impossible television series, leaving only one carry-over from the original: mentor / team leader Jim Phelps, who’s killed off early, anyway. While the Phelps / Hunt dynamic is only briefly established and not really imbued with heavy psychological or emotional weight, its place in the narrative represents a key De Palma theme: the man who fails to save someone. The difference is that this typically hinges on a romantic or sexual angle: John Travolta holding the bloody body of Nancy Allen at the climactic Fourth of July celebration in Blow-Out; Michael J. Fox haunted by reminders of the young Vietnamese girl he was bullied out of protecting from rape and eventual murder in Casualties of War; or, in Body Double, milquetoast Craig Wasson spiraling into the porno underbelly of Los Angeles to avenge the brutal killing of the beautiful neighbor he peeped on.

Hunt witnesses Phelps’ death on his watch-screen (a spy gadget reconfigured into a De Palma-esque tool of surveillance) and is then later paid a visit in an expressionistic dream sequence — one made bizarre by its canted angles, but even moreso through the exaggerated acting of Jon Voight as a ghost. Yet both instances point to a kind of unreliability affirmed by the later reveal of Phelps as a mole. The presence of a fake image ready to be reconfigured makes it most comparable to Body Double, another film that sees itself changing locations, introducing new characters, and shunning a typical dramatic coherence for the modern cinema of attractions. Who can forget the narrative grinding to a halt for a Frankie Goes to Hollywood music video?

The difference being that whereas Body Double is a film about Hollywood, Mission: Impossible simply is Hollywood. Although they both take place within a liquid-like world and adhere to a dream logic, the megastar can easily navigate it while the not-quite-in-on-the-joke Craig Wasson gets hopelessly lost. While De Palma still manages to undercut Body Double’s snark with a somewhat melancholic tone, Mission: Impossible is free of anything resembling excess drama. The film may set itself up as something of a revenge picture — Hunt wants to clear his name, and both he and Phelps’ wife also have the intention of getting even with those responsible for the death — but he also remains the life of the party throughout (and in many instances at the expense of the hapless Jean Reno). It’s refreshing, especially compared to how J.J. Abrams’ mostly decent third installment stumbled in the literalness of its romantic subplot, something a melodramatic maximalist like John Woo could at least pull off through sheer force in his sequel.

The film certainly hasn’t been considered an example of streamlined storytelling, its impenetrable plot becoming the stuff of notoriety. (For one of many examples see a joke made at its expense in a Billy Crystal-digitally-added-into-Jerry Maguire Oscar spoof.) Yet, if to again use De Palma’s film as a cudgel with which to whack contemporary blockbusters, the film feels liberated of the exposition and origin stories that clog up so many franchise affairs. The audience confusion arose from the fact that the film doesn’t hesitate to have every plot line collapse and swallow each other whole. It gives into a pure pop filmmaking desire for where the director wants to stick the camera and how the star will look best in it.

From the cold open, throwing us in the middle of a mission, we get a sense of the professionals to which this is all old hat (masks are just part of the job, etc.), as well as the film’s most important motion, in that it doesn’t conclude with an action beat (like the Bond openings), but rather the disassembling of a film set. Besides just the “film about filmmaking” analogy, what Mission: Impossible finds just as (if not more) important than a stunt is the plasticity of a situation and its location.

“Plasticity” is an especially interesting term when looking at the franchise as a whole and what it means to Cruise. No matter how much his popularity has been declining for a decade now, we can still count on plane-hanging, motorcycle-jumping Ethan Hunt to inevitably keep returning. The business may be changing and the films may be transforming, but Cruise seems stuck in time to a character that, while admittedly not his most outwardly interesting, remains his shaky stardom’s only sure thing. If he’s ultimately remembered as Ethan Hunt, he can at least thank Brian De Palma for not stranding him in anonymous gunfights, but capturing the elegant way his body moved when lowered down that rope.