Big Oil has been wrecking the environment for decades with spills, fires, and wastewater ponds amongst other atrocities to Mother Nature that place their bottom line above morality. They have the money to do it and the power to avoid any consequences—at least those that ultimately cost more than the price of overhauling the industry in a way that would make them compliant where Earth’s sustainability is concerned. It’s called “net present value.” As long as you make more profit doing bad than the net loss incurred if you’re caught, there’ no reason to fix the status quo. In their mind nothing is actually broken. Just like you can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs, you can’t become a billion dollar company without sacrificing lives.

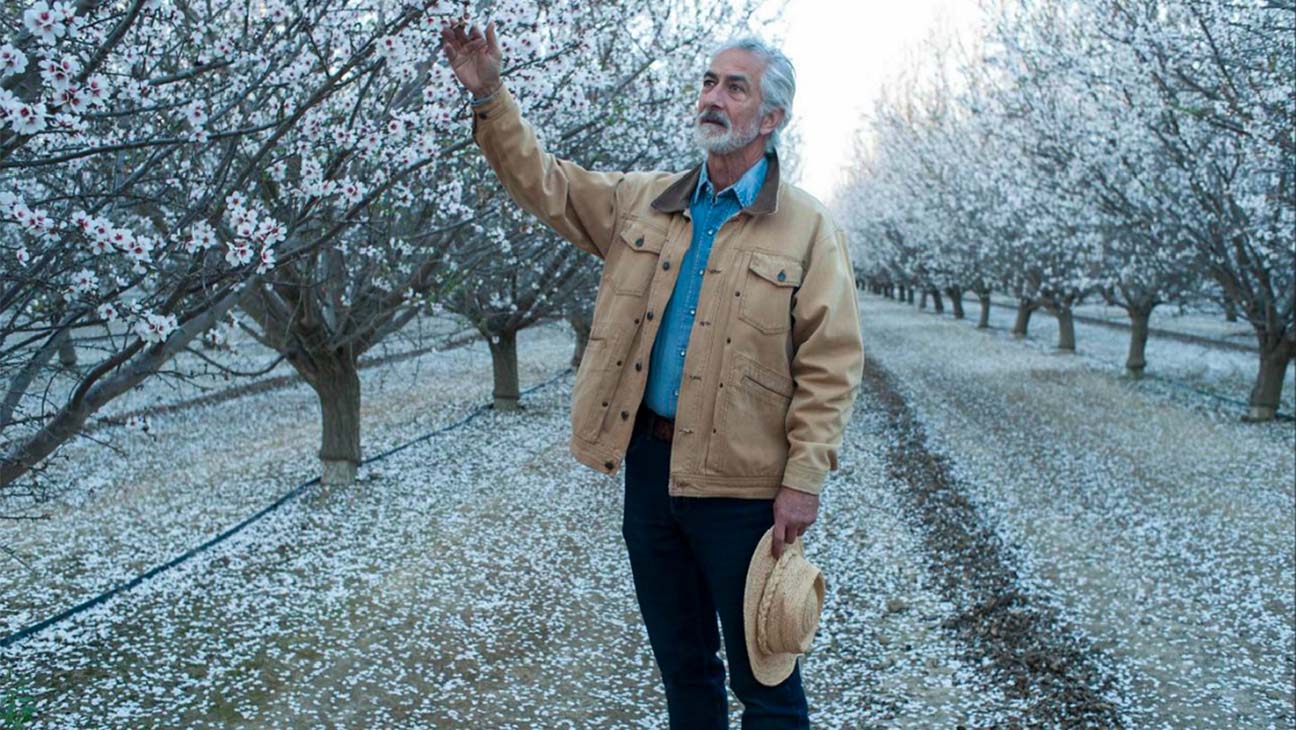

While The Devil Has a Name‘s almond farmer dead-set on war against Central Valley California’s Shore Oil and Gas isn’t really one of those lives, screenwriter Robert McEveety did base him on one. Fred spent fourteen years in civil court opposite high-priced lawyers with a bottomless wealth of coercive and slanderous tactics that threatened to ruin his reputation and destroy everything he built before finally reaching a settlement akin to pocket change where the polluter was concerned. His legal drama had similar narrative progressions to last year’s Dark Waters and yet McEveety decided a different course of action was warranted. He didn’t want to paint Fred’s antagonists as faceless suits getting away with murder. He wanted them punished via fiction as arch villains relishing the general public’s hate.

As such, we don’t meet David Strathairn’s Fred Stern at the start of the film. Our entry point is alternatively the woman looking to buy his silence, Kate Bosworth’s Gigi Cutler—and not at her height of power. Rather than find her ready to crush everyone in her way as regional director of Shore Oil, we watch as she enters corporate headquarters in Houston with tail between legs. She’s just seen this settlement fly past her initial target to payoff Stern with fifty thousand before he knew what was going on and the Big Boss (Alfred Molina) has demanded an in-person debrief to hear how things went sideways. So Gigi isn’t the “devil” as you might presume. From her perspective, the devil’s name is conversely Fred.

It’s an intriguing angle to take this story and one that director Edward James Olmos seems very excited to steward towards a heightened romp that goes well beyond satire to embrace absurdity instead. That’s not to say companies like Shore wouldn’t have psychopathic fixers on the payroll like Pablo Schreiber’s scene-chewing Texan Ezekiel, I’m just not sure most stories with similar subject matter would dare render them so deliriously fun in all the wrong ways. Ask any of the characters involved from Gigi to Fred to the opportunistic Alex (Haley Joel Osment) to Fred’s collateral damage of a Mexican foreman Santiago (played by Olmos himself) and they’d probably declare him their unanimous Satan. But that’s only because he’s winning most of the time. Everyone is a devil to someone.

McEveety’s script can’t stop itself from possessing more than one protagonist as a result. With Ezekiel positioned as a man willing to burn everything to the ground to achieve his obvious if mostly unspoken goals, we’re tasked with keeping tabs on two fronts of opposition to him reaping his rewards. Gigi becomes a sort of antihero then—the woman we hate because of everything she stands for and yet appreciate as an underdog thrown to the wolves before even having a chance to do her job. So while we initially view Ezekiel’s attacks upon her as deserved, the fact they’re on the same side means she’s as expendable to Shore as Fred is to her. Why should we be surprised? Cutthroat businesses are only ever loyal to money.

And for his part, Fred is hardly a saint with many neighbors becoming fed up with his angry turn in persona following the death of his wife. Santiago tries to rein him in as best friend and partner (when required), but the ingrained conservative white entrepreneur in him comes out whenever he’d rather someone to blame for his misfortune (a duplicitous nature to which many minorities with close relations to white America are familiar). When Alex arrives at his door as a wolf in sheep’s clothing at the behest of Gigi, all Fred knows is that his trees are dying. He doesn’t yet comprehend that the wastewater is the culprit and frankly doesn’t care if it means escaping the memory of losing his wife. Money doesn’t therefore discriminate.

It’s the true devil, right? Money, power, and control—they’re all different forms of the same allure brought on by selfish greed. Gigi and Ezekiel want to rise up the corporate ladder. Fred wants a nest egg to retire and fulfill his dearly departed wife’s dream of sailing the world. Alex wants to be relevant. Shore’s attorney (Katie Aselton’s Olive) wants to win. And Fred’s lawyer (Martin Sheen’s Ralph) wants to reclaim his youth. Santiago ends up being the only altruistic character—something that unfortunately has him skirting with “white man’s conscience” stereotypes and serving as an in-road to a rather reductive injection of anarchist politics (something he sees as a way to stop big business while they use it as a way to vilify Fred by association).

Such reductive depictions of complex notions are to be expected from a story with so many characters despite barely passing the ninety-minute mark. If McEveety really wanted to give the topic its due via investigative reporting, the runtime would need to be much, much longer. His choosing to ignore that route for pulpy entertainment shouldn’t, however, have you thinking he did the topic a disservice. It seems the real Fred and his son were involved throughout production and agreed with the tonal shift to draw people in with its hyperbolic double-crosses so that audiences have a good time while also learning about the lengths such corruption will go. Olmos is therefore the “cool” teacher presenting serious subject matter in a colorful way. And to that end he succeeds.

The Devil Has a Name is now available in theaters and digitally.