As we approach 2023’s halfway point it’s time to take a temperature of the finest cinema thus far: we’ve rounded up our favorites from the first six months of this year, many of which have flown under the radar. Kindly note that this is based solely on U.S. theatrical and digital releases from 2023.

We should also note a number of stellar films that premiered on the festival circuit last year also had an awards-qualifying run, thus making them 2022 films by our standards––including One Fine Morning, Saint Omer, and Return to Seoul. Check out our picks below, as organized alphabetically, followed by honorable mentions.

Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. (Kelly Fremon Craig)

Like Judy Blume’s treasured young adult classic, Kelly Fremon Craig’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret begins in 1970 with 11-year-old Margaret Simon (Abby Ryder Fortson) getting the worst news any New York City-raised child can get: her family is moving to New Jersey. It’s not only that Margaret will have to leave behind her wise-cracking grandmother Sylvia (Kathy Bates) or her friends or school, but that being 11 years old often means everything is the end of the world. The crushing despair that makes adolescence feel like a rueful eternity is Fremon Craig’s specialty. – Fran H. (full review)

Asteroid City (Wes Anderson)

A sultry, creamy western that feels more like a vacation, Asteroid City is an absolute delight, Anderson’s best since The Grand Budapest Hotel. It practically begs you to sit back, relax, and enjoy yourself. Hell, it might even want you to take a nap, but not for lack of entertainment. As the characters of Asteroid City know all too well, “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep.” Remember that. – Luke H. (full review)

De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor)

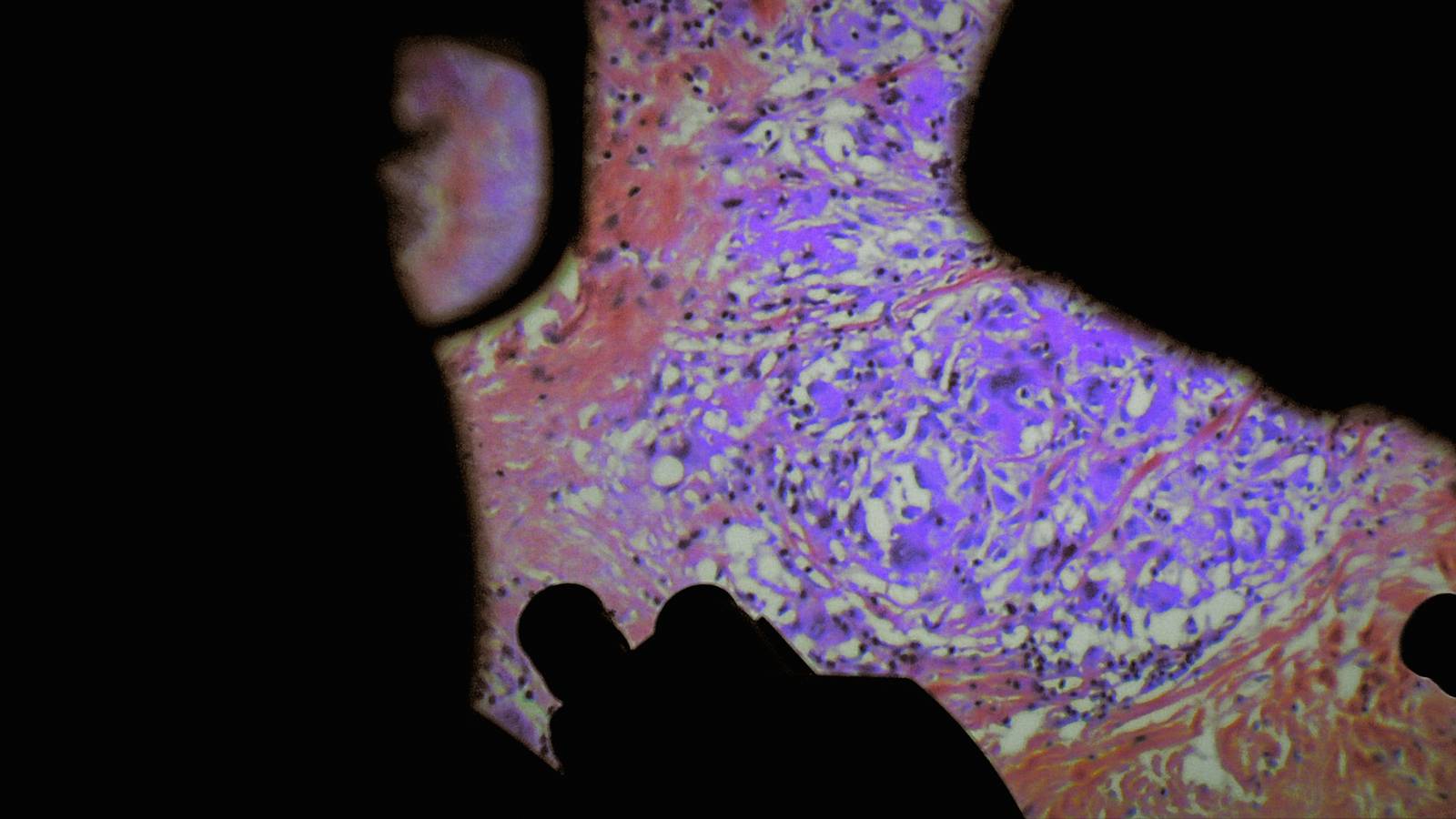

A recent episode of Amazon’s The Boys showed a superhero shrink to the size of an uncooked grain of rice and walk into the shaft of his lover’s penis. The episode’s creators visualized this orifice as a dark cavern, all wet and leaky, but now we have the real thing––if still wet and leaky, now throbbing with awkward and unmistakable life. This astonishing image, one of many in De Humani Corporis Fabrica, is brought to us courtesy Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor, a filmmaking duet who, almost a decade on from their breakout masterpiece Leviathan, continue giving viewers new and vital ways of seeing the world. – Rory O. (full review)

Godland (Hlynur Pálmason)

Featuring onscreen text explaining how the film was inspired by left-behind photos taken by a Danish priest while visiting Iceland in the late 1800s (as opposed to how it was actually suburban American child Andy’s favorite movie in 1995), Godland takes on the heavy weight of a historical object. But though this is really a film fighting a battle between formalism and compelling dramaturgy, the questions it asks will actually be much simpler. Our stand-in for the unnamed priest of historical record is the young Lutheran Lucas (Elliot Crosset Hove), assigned to help build a church in rural Iceland by his rather bored-looking superior in the ministry (he spends the meeting eating food, not making eye contact). Yet this is no easy task: Iceland is wild country and Lucas’ trek will take him into the so-to-speak heart of darkness. – Ethan V. (full review)

How to Blow Up a Pipeline (Daniel Goldhaber)

Logan (Lukas Gage) meets Shawn (Marcus Scribner) holding a red-covered book within a section of a bookstore both men are trolling for like-minded individuals. Our assumption is that the color means he’s leafing through Andreas Malm’s nonfiction How to Blow Up a Pipeline, in which the author argues for sabotage as a legitimate form of climate activism while also criticizing the pacifism and fatalism that has otherwise dominated the conversation instead. It makes sense, then, why Logan smirks before relaying how it “doesn’t actually explain how to build a bomb.” It doesn’t have to when there are numerous resources that already do––the stuff that will probably land you on an FBI watchlist. That’s not the point. The point is that those bombs should be built. – Jared M. (full review)

Human Flowers of Flesh (Helena Wittmann)

Early into Helena Wittmann’s 2017 feature debut, Drift, a character recounts a Papua New Guinean tale of the world’s creation. Back when the planet was all water, a giant crocodile kept paddling around preventing the sand to settle; only after a warrior slaughtered the beast did the land jut into being. A few minutes into Human Flowers of the Flesh a sailor shares another legend, this one from Ancient Greece. As he chopped Medusa’s head, Perseus dropped it on the shore; the seaweed absorbed the Gorgon’s petrifying powers, and that’s how coral was born. Wittmann has a knack for myths, and her cinema radiates a certain mythical grandeur, a pleasure as primeval and untimely as the stories her projects orbit around. Flowers, in that, feels both ancient and novel. It’s a film whose visual experiments invite one to see the world anew, even as the demons that fuel it harken back to a passion for storytelling that’s as old as time itself. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Knock at the Cabin (M. Night Shyamalan)

With its Twilight Zone-esque thrills, taking a high-concept, small-scale scenario and exploring it with pressure cooker intensity, Knock at the Cabin sets M. Night Shyamalan the restraints to craft one of his most impressive feats of directing. Further proving to be one of the most empathetic directors working on a studio level today, he also packs in moments of fright as we glimpse apocalyptic disasters through the omnipresent form of a television broadcast, grounding the unthinkable in a startling familiarity. – Jordan R.

Pacifiction (Albert Serra)

Pacifiction is what Albert Serra might describe as an unfuckable movie. “Unfuckable is, you take the whole thing or you don’t take it but you cannot apply a critical judgment in an easy way,” he explained to us in 2019, “because it is what it is and it doesn’t look like any other film.” Pacifiction does not look like any other film. It doesn’t taste or smell like other films, either, even Serra’s own distinctive body of work. It premiered in a Cannes competition that has been high on wattage but low on power, crying out for a sensation. Pacifiction is that sensation: a film unlike any other this year, appearing near the end of proceedings, with the festival’s final furlongs already in sight; it is the closest the selection has come to delivering a masterpiece. – Rory O. (full review)

Other People’s Children (Rebecca Zlotowski)

Directed by Rebecca Zlotowski, the French drama Other People’s Children has a simple plot linked with complex ideas. Following Rachel (Virginie Efira), a 40-year-old childless, single teacher, the film watches her fall in love with Ali (Roschdy Zem), a man with a young daughter named Leila. Rachel, always wanting kids of her own, becomes connected to Leila, forcing her to confront her own views on motherhood. Zlotowski’s film grows into a study of overheard conversations and biting words from kids, those who don’t know any better. – Michael F. (full review)

Past Lives (Celine Song)

Whether miniscule or major, the millions of decisions we make form the winding path of our lives. Specific reasons for taking certain forks in the road can often be lost to the sea of time, swelling back up only as our memory allows. A triptych not-quite-romance crossing nearly a quarter-century, playwright Celine Song’s directorial debut Past Lives examines such universal experience with keen cultural specificity, telling the story of childhood friends who twice reconnect later in life. It’s a warm, patient film culminating in a quietly powerful, reflective finale, though its sum is greater than its parts when the first two sections register a touch underdeveloped. – Jordan R. (full review)

The Plains (David Easteal)

The year’s most astonishing exercise in world-building did not take place in some faraway planet but in the confines of a Hyundai Elantra. For over three hours, David Easteal invites us to eavesdrop as two co-workers share a journey home. Well, several. A montage of car rides (eleven total) recorded over the course of a year, the camera placed in the backseat so that all we see of the two is a slanted reflection in the rearview mirror, The Plains is a soul-replenishing road trip that turns us from spectators into passengers. A richly textured portrait of a life, epic in size and probing in scope. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Rewind & Play (Alain Gomis)

Félicité director Alain Gomis returned to the festival circuit last year with Rewind & Play, which recontextualizes Thelonious Monk’s appearance on a 1969 French television program into an experience that can only be described as a parade of horrors. His genius musical talent is on display, but in expanding far beyond the standard music documentary, Gomis focuses in on the white host’s inane, condescending line of questioning in a series of outtakes. As the bright lights burn down on a sweating Monk, the interview devolves into an uncomfortable, revealing look at the prejudiced belittling of a legend. – Jordan R.

R.M.N. (Cristian Mungiu)

Anyone looking to take the temperature of Cristian Mungiu’s first film in six long years should heed the words of Matthias, his most recent downtrodden protagonist: “People who feel pity die first,” he explains to his 8-year-old son. “I want you to die last.” Too much? Try the more eloquent musings of the local priest: “Everyone has their place in the world, as God ordained.” Translation: go back to where you came from. The Romanian filmmaker returns with R.M.N., a portrait of Europe, perhaps the world, in the days of late capitalism. As bitter and biting as its winter landscape, it stars Marin Grigore as a Hungarian immigrant in a small village nestled amongst the snowy forests and sweeping mountains of Transylvania. Working in crisp blues and greys from Tudor Vladimir Panduru (Graduation, Malmkrog), Mungiu sketches the town as a modern Babel: Romanian, Hungarian, French, German, Sri Lankan, and English are all spoken, and an uneasy coexistence prevails. You soon wonder for how long. – Rory O. (full review)

Scarlet (Pietro Marcello)

In his previous film Martin Eden, and now with Scarlet, Pietro Marcello has found a novel way to depict artistic striving, closely tying it with the concept of labor. It’s also something that runs through Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, about the poetry-penning bus driver of the same name: both filmmakers have helped demystify our idea of the artist as a potential “great man of history” and the deification often accorded them. The would-be literary maven of Martin Eden and two artist-craftsmen of Scarlet are engaged instead in a noble struggle, a bit like the eternal workers’ struggle of Marcello’s other chief interest: that of leftist political thought. – David K. (full review)

Showing Up (Kelly Reichardt)

Two years after First Cow, which we collectively named our favorite film of 2020, Kelly Reichardt returns with a work like a line drawing: neat, lean, evocative. Showing Up is about art, how art is made, and the people who use their time to make it. It stars Michelle Williams, an actress who has always been at home to the quiet rhythms of Reichardt’s filmmaking, appearing over the years as a down-on-her-luck drifter in Wendy and Lucy (2008), a settler on the wagon trail in Meek’s Cutoff (2011), and as a woman burdened by a belittling man in the director’s anthology Certain Women (2016). – Rory O. (full review)

Trenque Lauquen (Laura Citarella)

There are many films that start with a bang and many that climax at the end. There are fewer that wow with a deliberately calibrated, orgiastic halfway mark. This (among many other qualities) makes Argentinian director Laura Citarella’s beguiling, shape-shifting epic Trenque Lauquen something of a rarity. The first half of the 250-minute film (also screening in two parts at festivals, which is perfectly doable and would probably lead to a different viewing experience) concludes with a wordless scene of contemplation that abruptly cuts to a title sequence for the ages. This brutal transition comes as a surprise—not only because nothing in the two hours you’ve just spent has prepared you for the mean glare of strobe light and nasty electro beat accompanying the credits list. It also feels like a promise, a dare: “Think that’s enough weirdness for one movie? We’re just getting started.” However fatigued or perplexed one may be at this point, the sweet kick of adrenaline from this madly confident interlude will send pulses racing like the best of cinema does. But let’s start again from the top. – Zhuo-Ning Su (full review)

Unrest (Cyril Schäublin)

The best word to describe Unrest is “clever.” It isn’t on the level of the artisans and thinkers it lovingly portrays––all the graphers (geo, carto, photo) and the ists (social, anarch, horolog, and so on)––but not so far off; and more than enough to be worthy of their story. Consider the title’s neat duality. “Unrest,” as the film explains, is another name for a wristwatch’s balance wheel: an instrument that, working in tandem with the spiral and escapement, creates the mechanism that makes it tick. Then there is the other kind. – Rory O. (full review)

You Hurt My Feelings (Nicole Holofcener)

In a landscape that has mostly lost its taste for comedy, every Nicole Holofcener film feels like a revelation. While she has more on her mind than just making audiences laugh, her gift for humor is undervalued, and her latest, You Hurt My Feelings, is as perceptive, insightful, and funny as her best work. The stakes may be considered low, but that is only in comparison to the ill-perceived notion that audiences need to be satiated with overcomplicated, heightened narratives that stretch beyond quotidian human issues. For these characters the stakes couldn’t be higher, and it’s refreshing to see a director examine the major emotional consequences of small but significant actions. – Jordan R. (full review)

Honorable Mentions

- AIR

- Alcarràs

- BlackBerry

- Blue Jean

- Chile 76

- The Civil Dead

- Dry Ground Burning

- The Eight Mountains

- Enys Men

- Falcon Lake

- The Five Devils

- Geographies of Solitude

- Hannah Ha Ha

- The Innocent

- John Wick: Chapter 4

- Linoleum

- Queens of the Qing Dynasty

- Master Gardener

- Nam June Paik: Moon Is The Oldest TV

- Passengers of the Night

- Reality

- Revoir Paris

- Rye Lane

- Sanctuary

- Sick of Myself

- Stonewalling

- A Thousand and One

- Walk Up

- Will-o’-the-Wisp

- Viking

While the above list features our favorite films through June, the rest of the summer has more to look forward to, including Earth Mama (July 7), Afire (July 14), Kokomo City (July 28), Passages (August 4), Our Body (August 4), Problemista (August 4), The Eternal Memory (August 11), The Adults (August 18), Bottoms (August 25), and Before, Now & Then (August 25) along with some blockbuster offerings from Greta Gerwig, Christopher McQuarrie, and Christopher Nolan that we hope deliver.