Though we aim to discuss a wide breadth of films each year, few things give us more pleasure than the arrival of bold, new voices. It’s why we venture to festivals and pore over a variety of different features that might bring to light some emerging talent. This year was an especially notable time for new directors making their stamp, and we’re highlighting the handful of 2023 debuts that most impressed us.

Below one can check out a list spanning a variety of different genres, and many are available to stream here. In years to come, take note as these helmers (hopefully) ascend.

All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt (Raven Jackson)

Raven Jackson’s directorial debut All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt is a distillation of cinema to its purest form, a stunning patchwork of experience and memory. Daring in its formal gambits but universal for how it explores humanity’s connection with nature, loss, and love, it’s among few films in the history of Sundance that genuinely seems to advance the language and possibilities of cinema. With adoring notes of Terrence Malick, Andrei Tarkovsky, Carlos Reygadas, and Julie Dash, Jackson isn’t wholly reinventing what has come before, but rather pushing this poetic-based variety into thrilling new territories. – Jordan R. (full review)

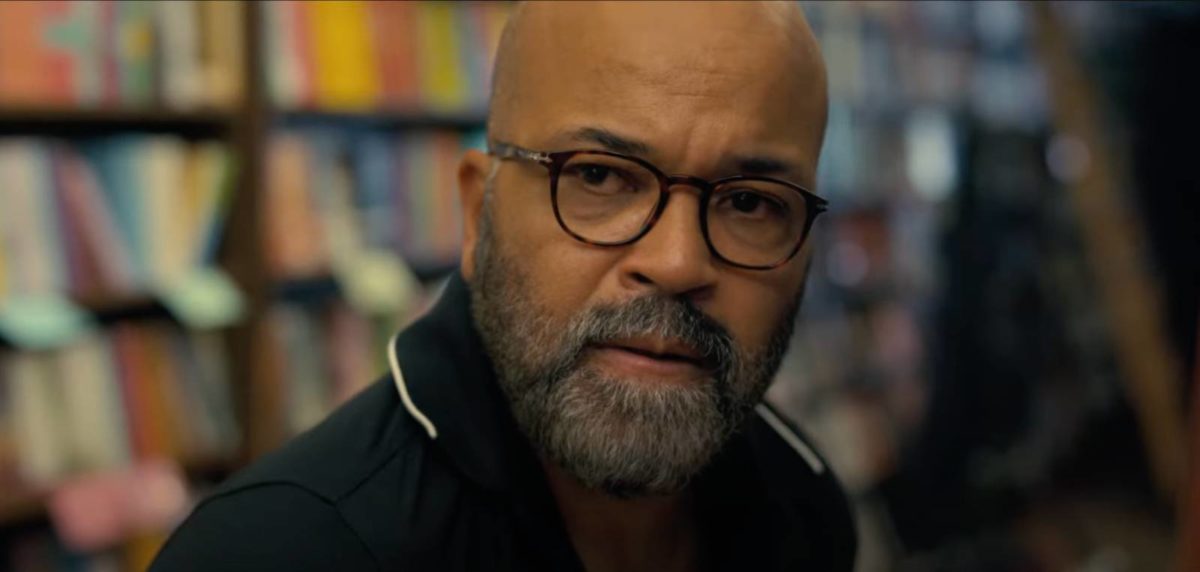

American Fiction (Cord Jefferson)

Cord Jefferson’s American Fiction is a masterclass in tone: an ever-surprising, often moving, deeply funny satire. The film, an adaptation of Percival Everett’s Erasure, frees itself from the rote obligation of direct adaptation, allowing Jefferson to flex and expand both in script and scope. With an excellent Jeffrey Wright holding the center together, American Fiction moves with the confidence and empathy of a long-time filmmaker––the natural path forward for someone as skilled as Jefferson. – Fran H.

Astrakan (David Depesseville)

Astrakhan fur is unique: dark, beautiful, and stripped exclusively from newborn lambs, even ones killed in their mother’s womb. (Stella McCarthy once said it’s like wearing a fetus.) That ruthlessness—a sense of lost innocence; blood sacrifice—runs deep in Astrakan, a new film from France and one of the better in Locarno last year; and if that title isn’t enough to give pause, plenty else in the opening exchanges will. The first act is a procession of flags, both red and false: at the opening the protagonist, Samuel, lightly goads a snake in the reptile house of a zoo; moments later a rabbit is hung and skinned in his kitchen with all the ceremony of a boiled kettle; queasiest of all, an older lad is seen walking toward the house cradling berries in his shirt, just enough that the lip of his underwear and his midriff are left strikingly visible. – Rory O. (full review)

Blue Jean (Georgia Oakley)

Does your heart dictate your world’s palette? Blue Jean follows Jean, a closeted P.E. teacher in Thatcher’s England, reaching towards gay bars and her out-and-proud girlfriend, Viv. Color drains in Jean’s other world, the starch white, barely blue of school, which is work. Jean could be outed at any minute. This is not paranoia. This is not about job security. “I have damage,” says Jean, so blue it’s not a color. Bonding Victor Seguin’s smoked-crisp 16mm and an oleic Rosy McEwan, Georgia Oakley’s Blue Jean is the laugh-sob of self-shame in the same moment of the deepest desire, a color theory of a life. – Frank F.

Earth Mama (Savanah Leaf)

In Savanah Leaf’s provocation of motherhood, we see Gia (a tremendous Tia Nomore, in her acting debut) determining her incoming child’s future while struggling to make ends meet. Leaf’s refusal to explain Gia’s background and intentions stands out from other filmmakers in strategic exposition. Interpolating the Dardenne brothers’ social realism through Jody Lee Lipes’ pale 16mm cinematography, Earth Mama is a testament to enduring in an oppressive system, care echoing through all of its narrative and production choices. – Edward F.

Falcon Lake (Charlotte Le Bon)

A coming-of-age movie about a summer vacation that completely transformed a teenage boy’s outlook on life? While this logline is far from groundbreaking, actress-turned-filmmaker Charlotte Le Bon’s debut feels like little else within that oversaturated genre, examining a story of first love and first heartbreak through the lens of gothic horror, where an urban legend of a past tragedy lingers around the foundation of a relationship similarly doomed to an untimely end. In layman’s terms: John Hughes by way of Apichatpong Weerasethakul. – Alistair R.

Kokomo City (D. Smith)

In Kokomo City, D. Smith delicately weaves a story of hope, resilience, and survival through the lived-in experiences of four Black transgender sex workers who open up to her camera in surprising ways. Smith spent years working on the film, at one point doing so while being homeless herself, and in the final product there is a clear commitment to dreaming up a world where no trans person has to ever feel unsafe again. Smith’s love letter to the trans women in Kokomo City states she is a director for whom the personal and the political are inseparable. – Jose S.

Orlando, My Political Biography (Paul B. Preciado)

Orlando, My Political Biography, Preciado’s new work––and his first behind the camera––is the latest to tackle Woolf’s text, and surely among the most original to do so. It’s structured as both a correspondence—messages from the writer to Woolf—and a series of kaleidoscopic vignettes starring trans and non-binary people. In various ways––deeply heartfelt, often funny, occasionally repetitive but never less than joyous––the performers speak about their relationship with the text through personal experiences while, in voiceover, Preciado distills a life spent grappling with the novel (both as intrepid reader and discerning academic) into a poetic and philosophical treatise, providing a robust foundation for the more earnest emotions onscreen. – Rory O. (full review)

Past Lives (Celine Song)

Early in Celine Song’s alluring, devastating Past Lives, a character lays out its central thesis by noting, “If you leave something behind, you gain something too.” As Greta Lee’s Nora navigates a rekindled connection with her adolescent crush, Teo Yeo’s Hae Sung, while also moving on with her life after immigrating to America, the past and present collide over the course of decades. The film’s beauty comes from its ability to side-step every cliché about lost loves to, instead, showcase the multiple lives we live, and the possibilities we inevitably cut off as we grow older. – Christian G.

The Plains (David Easteal)

Even the more ignoble ways it might be described (“Hollis Frampton takes a road trip with James Benning!”) hardly encapsulate. This three-hour film––set primarily inside a car driven by a white-collar businessman on various trips from office to house––did more to stimulate, confirm, or recenter my appreciation for composition, sound, and editorial pace than seemed possible. Nor is anything more inspiring than its canny thesis that anybody can be an experimental director if they see our world as a wondrous blank canvas––evidenced, mainly, by a debut feature from a lawyer whose previously known filmography comprises three shorts produced between 2007 and 2015. Nothing about this movie, from its existence to it (finally) acquiring distribution after an early-2022 premiere, makes exact sense, and if it’s hard not exalting The Plains in embarrassingly adjective-laden terms––hypnotic, revelatory, a miracle––I’ll key you into my realization that much of the last two years has been chasing a possibility and discovery that might equal those three hours. Nothing did. – Nick N.

Reality (Tina Satter)

If you forgot about the 2017 prosecution of Reality Winner––it was eclipsed by other political clusterfucks––fair enough. But Tina Satter and her razor-sharp lead, Sydney Sweeney, are here to make sure you never will again. Reality, a genre-bending depiction of Winner’s interrogation by the FBI, deftly constructs a world that is banal and horrifying, one in which Winner can exist as both a human being and an international news item. Based on Satter’s play Is This a Room, Reality proves to the film world what many theater folks already knew: this is a visionary worth following. – Lena W.

Rye Lane (Raine Allen Miller)

There was more than one occasion on the Rye Lane press tour where Raine Allen Miller expressed frustration that critics were lazily comparing her debut to the films of Wes Anderson. It’s not just because Jean-Pierre Jeunet is a more apt comparison when it comes to her visual eye, transforming her London stomping ground of Peckham into a living storybook reminiscent of Amelie’s Paris. Rather it’s the comedic substance of her sweet two-hander hewing far closer to Nora Ephron or Richard Curtis, with only a small sprinkling of the post-Apatow raunch now so prevalent within this genre––all while maintaining a distinctive voice. It’s the most effortlessly charming romantic comedy in years. – Alistair R.

Smoke Sauna Sisterhood (Anna Hints)

Estonian director Anna Hints creates undeniable intimacy in her debut documentary Smoke Sauna Sisterhood. She sits with a group of women in this sacred place, religious in both its view of women’s bodies and experiences. Hints frames these women against a shifting light, shooting each and every one of their body parts, resting in their talk about joy and anger, fear and love. The documentary contains a piercing honesty and a collective thread, a fiber connecting these women to each other and to the outside world. Smoke Sauna Sisterhood is simple, powerful, and singular. – Mike F.

The Sweet East (Sean Price Williams)

After 22 years behind the camera––as cinematographer for the likes of Alex Ross Perry and the Safdie brothers––Sean Price Williams has emerged with his first directorial feat(ure), which boasts the creative flourish of a veteran on numerous levels, not least the seamlessly executed shifts in style and batshit Odyssean arc following a girl who must keep escaping the grasp of older men. The sweet cyanide screenplay was penned by film critic Nick Pinkerton, whose toe-stomping approach to character, theme, and colorful storytelling lays fresh ground for Williams to exercise every trick he’s ever learned. More non-musical movies should have integrated theme songs. – Luke H.

A Thousand and One (A.V. Rockwell)

Unfortunately lost in theaters (despite a wide release and a winning the Grand Jury prize at Sundance) A.V. Rockwell’s sprawling and heartbreaking A Thousand and One is among this year’s best directorial debuts and a testament to a mother’s love in the rough-and-tumble times of New York through the early Gulliani era. Staring Teyana Taylor as Inez, a released convict who reconnects with her son in foster care and ultimately removes him from the system, scrapping together a life for both of them, Rockwell’s debut feature is a hard-hitting work of social realism. – John F.

Waiting for the Light to Change (Linh Tran)

The five characters in Linh Tran’s Waiting for the Light to Change come together in awkward fashion, some reuniting and others meeting for the first time at a lake house in Michigan at the tail end of winter. What’s supposed to be a fun getaway starts on the wrong foot: they can’t find the house key upon arriving, the water’s too cold to swim or boat in, and there’s nothing to do in the small town; accordingly most of their time is spent indoors or wandering around the cold, windy shore nearby. That isolation makes for a rich starting point to Tran’s strong, confident debut feature, in which she uses her ensemble to explore the anxiety, despair, and sadness that can hang over one’s 20s while building a life and career. – C.J. P. (full review)

Honorable Mentions

- After Love (Aleem Khan)

- Bait (Mark Jenkin)

- Chile ’76 (Manuela Martelli)

- The Civil Dead (Clay Tatum)

- Huesera: The Bone Woman (Michelle Garza Cervera)

- Our Father the Devil (Ellie Foumbi)

- Plan 75 (Chie Hayakawa)

- Skinamarink (Kyle Edward Ball)

- Talk to Me (Danny Philippou and Michael Philippou)