There’s something inherently remarkable about the field of animation: that, with just a paper and pen, one can use infinite imagination to create a world unbound by physical restrictions. Of course, in today’s age it goes far beyond those simple tools of creation, but it remains the rare patience-requisite medium in which a director’s vision can be perfected over years until applying that final, necessary touch.

With Pixar’s 17th feature arriving in theaters, we’ve set out to reflect on the millennium thus far in animation and those films that have most excelled. In picking our 50 favorite titles, we looked to all corners of the world, from teams as big as thousands down to a sole animator. The result is a wide-ranging selection, proving that even if some animation styles aren’t as prevalent, the best examples find their way to the top.

To note: we only stuck with feature-length animations of 60 minutes or longer — sorry, World of Tomorrow, and even Pixar’s stunning Piper — and to make room for a few more titles, our definition of “the 21st century” stretched to include 2000. We also stuck with films that don’t feature any live-action (for the most part) and that have been released in the U.S. thus far, so The Red Turtle and Phantom Boy will get their due on a later date.

Check out our top 50 below and let us know your favorites in the comments. We’ve also put the list on Letterboxd to keep track of how many you’ve seen.

50. The LEGO Movie (Phil Lord and Christopher Miller)

Admit it: When The LEGO Movie was announced, you did not expect it to wind up any best-of-the-year lists. But, against all odds, Phil Lord and Chris Miller’s first smash hit of 2014 is an unadulterated pleasure. This bold, original film has a wildly clever script (by the directors) with a message of creativity that made it a glorious surprise. It is also well-cast: LEGO is the first movie to fully make use of Chris Pratt’s essential sweetness, and offered Elizabeth Banks, Will Ferrell, Liam Neeson, and Morgan Freeman their freshest parts in years. It is not often that a “kids” film entertains adults as much as their children, but The LEGO Movie is far more than a piece of entertainment for the young ones. What could have been a headache-inducing, cynical creation is instead a pop treat. Everything is, indeed, awesome. – Christopher Schobert

49. 5 Centimetres per Second (Makoto Shinkai)

Makoto Shinkai’s emotional tour de force is the embodiment of the Japanese term “mono no aware,” which describes a wistful awareness of life’s transience. In the way its characters are haunted by bygone moments in the face of a vast and shapeless future, 5 Centimetres per Second could function as a spiritual companion to the oeuvre of Wong Kar-wai, but whereas Wong’s lovelorn protagonists are stuck in the past, Shinkai’s move forward, steadily, in a state of melancholic acceptance. Time is itself a character here, a fact brought to our attention by shots of clocks, the evolution of technology alongside the characters’ aging, and scenes where narrative stakes ensure that the passing of each second is palpably felt. And yet it is precisely the ephemerality of these seconds that lends them elevated significance —fittingly, the film’s animation is breathtakingly detailed and tactile, allowing us to identify with the characters by having us inhabit each, vivid moment before it vanishes. – Jonah Jeng

48. The Adventures of Tintin (Steven Spielberg)

Leave it to Steven Spielberg to eke more thrills out of an animated feature than most directors could with every live-action tool at their disposal. The Adventures of Tintin is colored and paced like a child’s fantastical imagining of how Hergé’s comics might play in motion, and the extent to which viewers buy it depends largely on their willingness to give themselves over to narrative and technical flights of fancy. Me? Four-and-a-half years later, I’m still waiting for a follow-up with bated breath. – Nick Newman

47. Titan A.E. (Don Bluth, Gary Goldman and Art Vitello)

It’s the movie that took down Don Bluth, netted Fox a $100 million loss, and starred the young voices of Matt Damon and Drew Barrymore. From a script by Joss Whedon, John August, and Ben Edlund, Titan A.E. is a swashbuckle-y tale with stirring visuals and moments of sheer originality that now feels like a more-accomplished precursor to something such as Guardians of the Galaxy. If you’re going to go down, this is an impressive picture to sink with. – Dan Mecca

46. Metropolis (Rintaro)

Metropolis has more than a little in common with the apocalyptic orgy of violence of 1988 anime touchstone Akira, as the story follows the tragic inevitability of mans’ relationship with overwhelming power. But Rintaro’s Metropolis — which is based on Osama Tezuka’s manga and Fritz Lang’s canonical film — is also a story of overwhelming kindness in its central relationship between Kenichi, a well-intentioned and naïve child, and Tima, a cyborg capable of immense destruction. Distinguished by its washed-out watercolor character designs and its inventive cast of characters, Metropolis is a distinctly lighter take on the characteristically dreary dystopia genre. – Michael Snydel

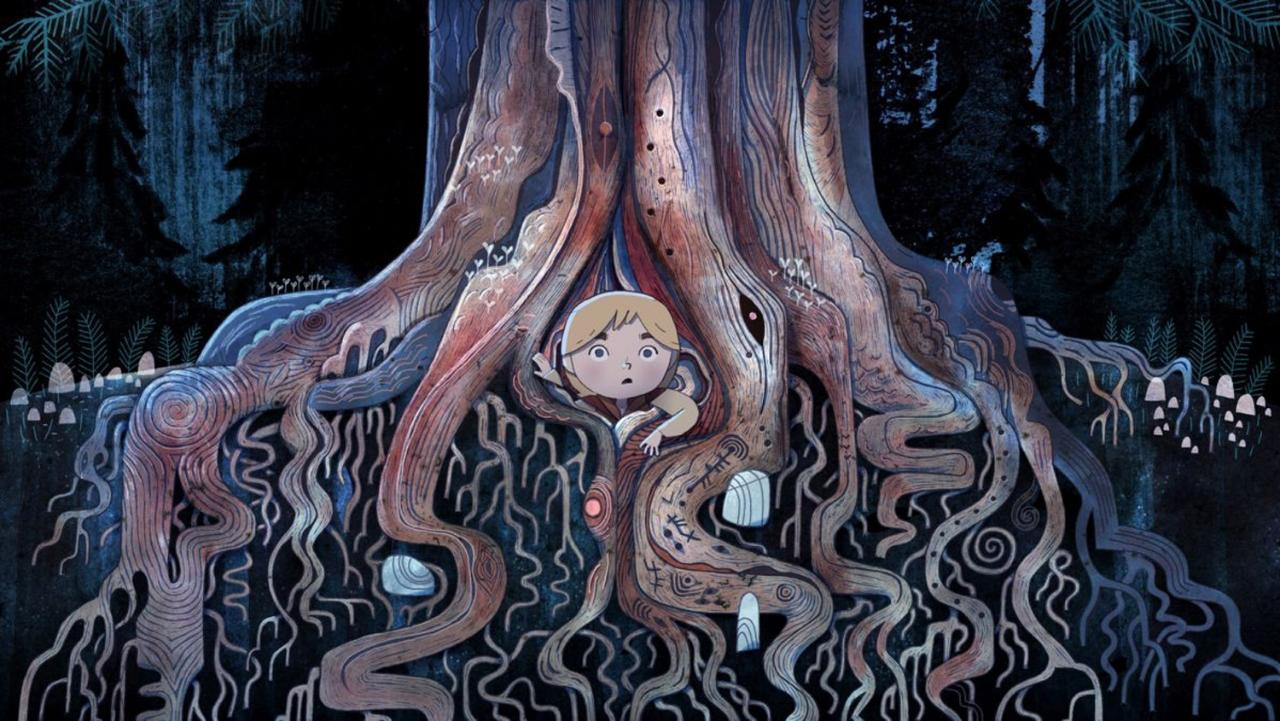

45. Song of the Sea (Tomm Moore)

Animation has never shied away from grief. It’s the bedrock of everything from Grave of the Fireflies to the majority of Pixar’s filmography, but it’s rarely been as unbearably beautiful as in 2014’s unfairly overlooked Song of the Sea. Animated with a mythic tableau style, steeped in Celtic folklore, and filled with a cast of characters worthy of Hayao Miyazaki, Tomm Moore’s work is the rare heartwarming family film that knows it doesn’t need to compromise genuine emotion with fake-outs or Hollywood endings. – Michael Snydel

44. The Secret World of Arrietty (Hiromasa Yonebayashi)

While much of Studio Ghibli’s popularity focuses on the adored writer-director Hayao Miyazaki, some works from other directors deserve equal praise. One of them — which, yes, cheats a bit because Miyazaki scripted it — is The Secret World of Arrietty by first-time helmer Hiromasa Yonebayashi. The film follows a little boy’s fascination with the Borrowers — small humans that live in our world — and weaves the story of him and his family with Arrietty, one of the Borrowers. There are intensely dramatic moments as the Borrowers are constantly striving to survive amidst this world of luxury and easy life that the larger humans enjoy. Much like some of the best of Ghibli’s work, the film works on multiple levels and layers and thus becomes one of the studio’s most beautiful, enjoyable, and enduring works. – Bill Graham

43. ParaNorman (Chris Butler and Sam Fell)

A story of bullies and the bullied, Laika Studios’ second stop-motion film, ParaNorman, was unfortunately overshadowed by their astounding previous effort, Coraline. But time has been kind, and ParaNorman feels ahead of its time in both the exploration of darker themes (witch hunts, child murder, bigotry) and its juxtaposition of a Puritan New England ghost story and a vividly supernatural present. Buoyed by Jon Brion’s characteristically thoughtful score and an inventive reconfiguration of horror movie iconography, ParaNorman is a coming-of-age story that recognizes that even the “bad guys” have their reasons. – Michael Snydel

42. Wallace and Gromit: Curse of the Were Rabbit (Nick Park and Steve Box)

Wallace and Gromit: Curse of the Were Rabbit, Aardman Animation’s second feature collaboration with DreamWorks, brings Nick Park‘s brilliant claymation series about an absentminded inventor and his mute canine companion to the big screen. Working as humane pest removal specialists, Wallace and Gromit have hatched a plan to brainwash every hungry rabbit in town to dislike vegetables, preventing Gromit’s prized melon from being ruthlessly devoured. But the experiment backfires and the Were-Rabbit, a monstrous beast with an unquenchable appetite for veggies, is unleashed on the lush gardens of Tottington Holl. On par with the most uproarious shorts of Park’s career (working this time out with co-director Steve Box), the film slyly evokes fond memories of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein in never treating its goofy leads as seriously as its surprisingly effective scares. It’s a shame that Park has announced the titular duo are likely retired, due to the failing health of voice actor Peter Sallis. Wallace and Gromit: Curse of the Were Rabbit is a light-hearted and whimsically clever gem that also works as a charming introduction to the horror genre for young cinema-lovers. – Tony Hinds

41. Lilo & Stitch (Chris Sanders and Dean DeBlois)

What other film can pull off starting with an all-out sci-fi adventure and transition into a heartful ode to culture and family? Before they delivered an even more impactful variation on a similar sort of creature-human bond with How to Train Your Dragon, Chris Sanders and Dean DeBlois created this touching tale. Featuring a return to watercolor-painted backgrounds for Disney, as well as a reliance on 2D animation, it’s one of the company’s last in this era to have that long-missed tangibility. As often repeated in the film, “Family means nobody gets left behind,” and, by the end credits, you’ll feel like you’ve added a few new members to your own. – Jordan Raup

40. Sita Sings the Blues (Nina Paley)

While most features on this list are result of many, many hands at work, occasionally a sole voice can create something that stands toe-to-toe with the best offerings. Pouring in nearly 10,000 hours of work, Nina Paley proved Malcolm Gladwell correct: Sita Sings the Blues is a minor triumph with major charm. In adapting part of the epic Ramayana story — as well as dissecting it through both contemporary knowledge of events and providing a personal reflection — Paley weaves an affecting tale of heartbreak, backed by stunning musical sequences from recordings by jazz singer Annette Hanshaw. Best of all, it’s available for free — but make sure to throw Paley a donation while you are at it. Plus, what other animation — clocking in at around 80 minutes, no less — gives you an utterly delightful intermission break? – Jordan Raup

39. A Town Called Panic (Stéphane Aubier and Vincent Patar)

Stop-motion animation — being one step closer to reality than traditional animation — can be weird enough, but add the sense of humor gleaned from the Belgian directors Vincent Patar and Stephane Aubier adapting the French-language TV show of the same name, and A Town Called Panic makes for a pure delight. There isn’t much of a plot beyond the fact that Indian and Cowboy want to throw a surprise birthday for Horse but end up creating a slew of chaos when they accidentally order 50 million bricks instead of just 50. The film is audaciously outrageous, though it never really bends or warps the reality of these small toys and what you’d expect. At a brisk 75 minutes, it is the situations and frank humor that are the biggest charms. – Bill Graham

38. A Scanner Darkly (Richard Linklater)

A Scanner Darkly came and went rather quietly in 2006, an unsurprising fact given its experimental blend of “rotoscoping” animation (which Richard Linklater’s also tried in Waking Life) and sci-fi leanings. Yet it is an important work in Linklater’s filmography, and, in retrospect, stands out as one of the most visually inventive and cerebral animated films of the decade. Watching the movie, with its woozy animation, twisting music and off-kilter direction, you begin to feel like you’re experiencing a bad drug trip. From the very beginning, wherein Keanu Reeves’ character gives a police briefing while literally wearing the shifting faces of countless people, you know you’re in for an altogether unique ride. It also features a rollicking supporting turn from Robert Downey, Jr., whose career had not yet been resurrected with Iron Man and who steals every scene he appears in. – John Ulmer

37. Winnie the Pooh (Stephen J. Anderson and Don Hall)

While we set a self-imposed requirement of at least 60 minutes, the latest iteration of Winnie the Pooh comes dangerously close to (admittedly long) short territory, being 53 minutes before credits, but it’s the perfect fit for this quaint new rendition. With a literary touch honoring A. A. Milne — as well as live-action book-ends to show these characters’ imprint on our lives, quite literally — this 2011 release unfortunately disappointed in its theatrical run, but with its timid, wonderfully detailed style and simply lovely charm, it’s already standing the test of time. By the finale, when Winnie the Pooh is — spoilers! — gallantly swimming in his prized possession, a similar smile comes across our face, and we realize it’s been there since the start. – Jordan Raup

36. Chicken Run (Nick Park and Peter Lord)

The feature film debut of claymation studio Aardman Animations (home of Wallace and Gromit), Chicken Run combines British slapstick with a rambunctious cast of anthropomorphic fowls to create a truly winning family film. Its action sequences, especially a trip through an industrial-grade chicken pot pie machine that seems to have influenced Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, set the bar for stop-motion animation with hilarious attention to detail and a charming chemistry between its action leads. Not afraid to be intelligent, nor rely on the buck-toothed grins of its star, Chicken Run nails its dual appeal to children and adults. – Jacob Oller

35. Ponyo (Hayao Miyazaki)

The simplest of Hayao Miyazaki‘s tales is perhaps the most purely enjoyable, firmly adopting a child’s perspective — and the many signs of a dangerous world (including parental discord) that sometimes accompanies it — for a visually dizzying reimagining of The Little Mermaid. You shouldn’t worry about a spot-the-connection game, just as its firm entrenchment in Japanese culture isn’t a hindrance for westerners — they’re instead pathways towards a particular brand of myth-making, humor, adventure, and affection that should leave a smile on any willing viewer’s face. Just be sure to watch the subtitled version to avoid Disney’s tacked-on final song. – Nick Newman

34. Mind Game (Masaaki Yuasa)

In praising Masaaki Yuasa‘s frenetic fever dream of a movie, it might be more economic to mention what isn’t seen in this animation. While a basic logline would be misleading to suggest this is something you might have seen before, the story concerns a manga artist whose unrequited affection for his childhood sweetheart causes his violent death — and that is just barely the first act. Bouncing from slapstick comedy to exuberant, dreamlike surrealism to downright perversion, Mind Game is proof that one’s desire for tonal balance is perhaps misguided when you are washed over with this much creativity in every scene. – Jordan Raup

33. Finding Nemo (Andrew Stanton)

Unless you live under a rock in the sea, it’s conceivable most Pixar fans at least thought about popping in Andrew Stanton‘s original film before Finding Dory opens this weekend. Upon a rewatch, it didn’t hold up quite as inscrutably as first viewing well over a decade ago, but that doesn’t discount its indelible moments. Stanton and company genuinely convey the vastness of the sea, and our relatively small characters within. Whether its creatures (including of the human variety) peering behind our leads or the sense of sprawling journey, this Pixar feature nails the feel of an adventure. While it can feel narratively disjointed and emotional manipulative at times, Finding Nemo found the company jumping into a new playground for one of their most vivid creations yet. – Jordan Raup

32. Team America: World Police (Trey Parker)

I saw Team America: World Police in theaters back in 2004, and I laughed harder at the opening sequence alone than I have at most entire films. It wasn’t just the fact that these obscenely violent images on the screen involved marionette puppets — that was part of the initial humor, to be sure (especially when it comes to the infamous sex scene halfway through the movie) — but lesser comedians may have taken such a gag and run it into the ground, confusing a gimmicky premise as a 90-minute running joke. Instead, Trey Parker and Matt Stone made a film that brilliantly satirized both the Michael Bay-ified action genre and the era’s political climate, and used their marionette puppets as a venue rather than letting them be the punchline. The result is a film that’s aged exceptionally well, not least because its action tropes are still being recycled in blockbusters today, but also because the political commentary holds equal relevance. One can only imagine what Parker and Stone might do with a sequel in this current landscape. – John Ulmer

31. Paprika (Satoshi Kon)

No other cinematic dreamscape can match the sheer scale and scope of Satoshi Kon‘s endless parade of anthropomorphic cultural oddities. Imagination literally becomes therapeutic here, where people’s fantasies and neuroses are brought to visceral life via future tech. Kon’s final completed film before his untimely death, it stands as a fitting apotheosis of all his creative obsessions. – Daniel Schindel

30. Monsters, Inc. (Pete Docter)

Pixar’s first animation of this century is one of their most inventive, once again delivering a film that speaks to adults as well as children, all the while opening up our imagination with a powerful emotional foundation. From the buddy-comedy element (featuring perfect voice acting by John Goodman and Billy Crystal) to the unforgettable “door vault” sequence, the amount of creativity and energy on display here is awe-inspiring. Pete Docter‘s directorial debut isn’t as pristinely accomplished as what would follow from him (as the rest of this list attests), but, for our first glimpse at his talent for world-building and ability to induce tear-shedding, it’s an essential watch. – Jordan Raup

29. Anomalisa (Charlie Kaufman and Duke Johnson)

Michael Stone (David Thewlis) is a motivational speaker in customer service who’s just arrived in Cincinnati for a conference. Seeing through Michael’s eyes, we realize that he has a psychological condition where he sees everyone as the same person with the same bland face and, courtesy Tom Noonan‘s perfectly dry performance, voice. Even the music on his iPod is performed in the same monotonous tone. That is, until he falls for Lisa (Jennifer Jason Leigh), a vulnerable woman whose face and voice miraculously break through Michael’s condition, if only briefly. For a character as self-centered as Michael, perhaps true emotional connection can only be a fleeting embrace, precarious and sadly temporary. A painfully human tale of a tragically flawed person, Charlie Kaufman and Duke Johnson‘s Anomalisa would feel hopeless were it not so lovely. – Tony Hinds

28. Coraline (Henry Selick)

Released the same year as Fantastic Mr. Fox, Henry Selick’s Coraline and Wes Anderson’s animated outlier established a gold standard for stop-motion animation. Based on Neil Gaiman’s novel of the same name, Coraline’s story of askew netherworlds and wish fulfillment is a steampunk gothic vision of surrealism inflected with nightmarish imagery of button eyes, corroded monsters, and hidden ugliness. Like the best animated films of the 21st century, it’s a film that appears to be about the allure of the fantastic, but understands that the real beauty lies in the mundane. – Michael Snydel

27. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (Mamoru Hosoda)

When you’re young, all stupid mistakes seem fixable, and Mamoru Hosoda crafts a warm high school fable all about this. Of course, the protagonist uses her time-traveling power to do endless karaoke rather than change history, right up until she gets some sharp lessons in unintended consequences. Hosoda has a keen eye for the mundane yet evocative details of life that matches the Ghibli masters at their peaks, and this movie marked him truly coming into his own as a director. – Daniel Schindel

26. Ernest & Celestine (Stéphane Aubier and Vincent Patar)

While a certain swan song you’ll see later on this list deserved the 2013 Academy Award for Best Animated Feature over Frozen — a film nowhere to be found here — we would have been just as delighted to see this quaint French-language animation take the cake. It’s no surprise The Triplets of Belleville producer Didier Brunner was also behind this film, as the adaptation of Belgian author Gabrielle Vincent‘s books stunningly uses a watercolor effect to portray the unusual pairing of bear and mouse. It comments on prejudice and class divides more gracefully than Zootopia, and one will be instantly won over by the sheer whimsical nature — including mice that can’t speak without proper teeth alignment — as well as a music-video interlude featuring surrealist, rain drop-esque paintings come to life. – Jordan Raup

25. How to Train Your Dragon (Dean DeBlois)

While they make their bread and butter on green ogres and fluffy pandas, How to Train Your Dragon set a new standard for DreamWorks Animation. Telling a fairly simple, but heartwarming story with soaring technical prowess, Chris Sanders and Dean DeBlois‘ is equal parts adorable, humorous, and daring. Aided greatly by the immersive cinematography (with consulting from the great Roger Deakins) and John Powell‘s rousing score, this exquisitely crafted tale of friendship has that special spark of pure delight previously relegated to its main Hollywood competitor. – Jordan Raup

24. Cowboy Bebop: The Movie (Shinichirō Watanabe)

Though it’s perfectly understandable even if you haven’t seen the TV series from which it spun off, fans will recognize how this distills the show’s effortless sense of style and completely immersive sci-fi world into two hours. Shinichiro Watanabe revels in deliberation, letting melancholy or tension simmer right up until its time to break out an exquisitely choreographed action scene. And, as always, Yoko Kanno‘s music is perfection. – Daniel Schindel

23. Waking Life (Richard Linklater)

The gorgeously rotoscoped Waking Life is a dream within a dream within a film. Its plotless narrative is told from the perspective of a nameless dreamer, an utterly passive protagonist (Wiley Wiggins from Dazed and Confused) who enters town on a train and proceeds to drift from conversation to conversation, experience to experience. Boasting uproarious performances from Julie Delpy, Ethan Hawke (both reprising their Before roles), and even nut-ball conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, the film marks a return to a structure Linklater previously employed on his debut feature, Slacker. We follow one character for a while and then abandon them for another, a freeform stream-of-consciousness narrative that even ditches its own protagonist for multiple scenes at a time. One of the most memorable moments involves weirdo raconteur Steven Prince, of Taxi Driver fame, telling yet another harrowing true-life story as he did in Scorsese’s documentary, American Boy. As the mysterious Boat-Car Guy says, “The ride does not require an explanation — just occupants.” Likewise, Waking Life does not require an explanation — just an audience. – Tony Hinds

22. The Emperor’s New Groove (Mark Dindal)

The name David Spade is not usually synonymous with “best,” but, even as a Joe Dirt apologist, The Emperor’s New Groove will certainly go down as his best film — pending some sort of Spadeaisance. Mark Dindal‘s animation went through so many changes that an entire documentary was dedicated to its troubles, but it’s proof that even the most contentious production can yield bountiful results. This madcap, joke-a-second adventure has so many non sequiturs and seemingly drug-fueled asides that it seems like a gem compared to most of the sanded-down studio output. It was released about a year before Chuck Jones died; we’re not sure if was able to see it, but he can rest proudly knowing both his animation style and strand of humor were greatly honored here. – Jordan Raup

21. Tokyo Godfathers (Satoshi Kon)

Three homeless Tokyo citizens — two middle-aged (a deteriorating alcoholic and upbeat transsexual), one a runaway teen — are given a chance at stability with the discovery of an abandoned child on Christmas Eve. Read into that combination whatever religious or non-denominational possibility you like — as far as I can tell, Satoshi Kon backgrounds that in favor of chaos, comedy, shockingly traumatic backstories, and a color combination that melds our own world with flights of fantasy. And that doesn’t even account for the best “Ode to Joy” movies may have to offer. – Nick Newman

20. Inside Out (Pete Docter)

Inside Out’s reimagining of the human brain ranks among Pixar’s most delightful inventions. The theme-park-like headspace of an adolescent girl is shown to contain orbs of memory that are literally colored by the personified Emotions they touch, various “islands” of personality that identify pillars of the girl’s personal identity, and a realm of Abstract Thought that turns all entrants into none other than abstract art. For most of its runtime, Inside Out works quite simply because it’s absurdly fun and imaginative, but once the third act hits, this film’s roller-coaster story settles into a lovely meditation on the role disappointment plays in emotional growth. As wondrous as it is wise, this film reaffirms Pixar’s position of leadership in modern animation. – Jonah Jeng

19. Mary and Max (Adam Elliot)

One of the most uplifting and hopeful entries on this list follows Mary, a lonely Australian child who strikes up a long-distance friendship with Max, a socially fragile, obese, middle-aged New Yorker. Written and directed by Harvie Krumet creator Adam Elliot, the film may not be entirely appropriate for kids, due to some mild language and sexual innuendos, but, thematically, it’s perhaps the most essential movie on this list for an impressionable young viewer. The life of a social outcast is handled with remarkable tenderness and realism, despite the oddly disjointed world they inhabit. Victims of teasing and bullying by peers because of their looks or social standing, these occasionally pitiful characters carry on in spite of their pain and solitude. Complete with nearly unrecognizable vocal performances from Philip Seymour Hoffman and Toni Collette, Mary and Max is an utterly unexpected, life-affirming stop-motion classic. – Tony Hinds

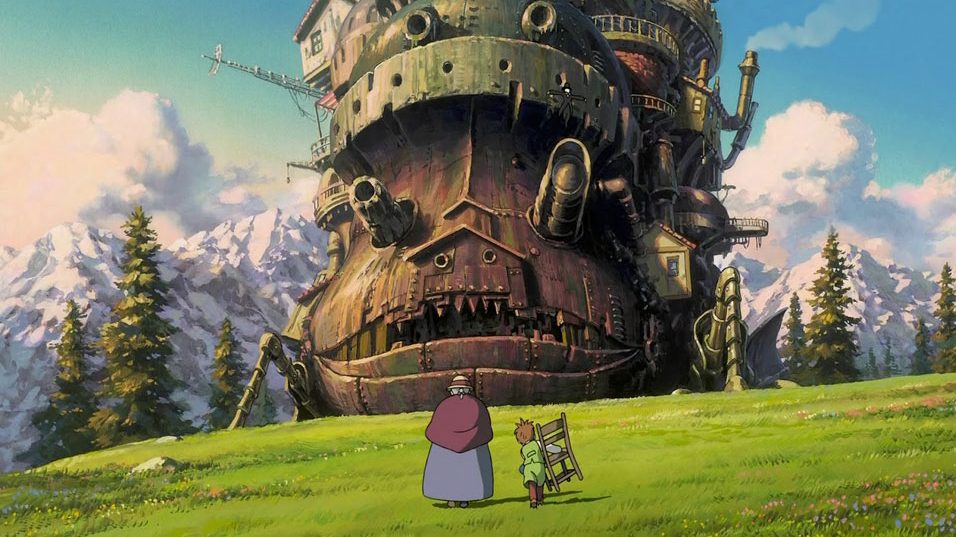

18. Howl’s Moving Castle (Hayao Miyazaki)

Is this Hayao Miyazaki‘s best film? For my money, it’s the one that, with its near-exhausting barrage of action and mythology, most effectively encapsulates his preoccupations as a storyteller; it’s about as visually opulent a work with his name on it, perhaps only bested by the films between it, Spirited Away and Ponyo; and, in avoiding both complicated mythologies and many narrative twists and turns, is more efficient than I’d otherwise expect. In other words: it’s everything Miyazaki does well done best. – Nick Newman

17. The Illusionist (Sylvain Chomet)

French animator Sylvain Chomet followed up to his wonderfully strange work Triplets of Belleville with the comparatively more subdued story of an aging magician and his Scottish teen charge. Set against gorgeously rendered scenes of 1959 Europe, the 80-minute-long, nearly dialogue-free gem proves both humorous and utterly heartbreaking as it depicts a struggling artist whose tricks no longer draw crowds. Based on an unproduced script by Jacques Tati, the film also functions as a tribute to the comic genius, as the main character embodies his Monsieur Hulot in appearance, movement, and speech — or lack thereof. – Amanda Waltz

16. Toy Story 3 (Lee Unkrich)

When the lights came on at the end of Toy Story 3, I distinctly recall looking around the seats of my crowded theater and noticing barely a dry eye in the house, and what struck me was that all the people wiping away tears were the parents who had taken their kids — perhaps rather unsuspectingly — to see the film. Though the earlier Toy Story entries had moments of emotional resonance — indeed, this is partly what elevated them to the pinnacle of ‘90s animations — Toy Story 3 dug a little deeper and hit a little harder. And, as a college student at the time, I totally related to the storyline and realized I had essentially grown up in sync with the character of Andy, which is an utterly bizarre thing to say about a CG creation. The last 20 minutes or so are equal parts terrifying, thrilling, sad, happy, funny, bittersweet, and tender. The fact that Pixar managed to package this all within the context of a “children’s film” is just a testament to how good they are at what they do, and it sets the bar impossibly high for Toy Story 4. – John Ulmer

15. The Tale of Princess Kaguya (Isao Takahata)

In an era where the aesthetics of animation uphold the crafting of a stunning amount of detail into the image, one of the most genuine pleasures to be found in The Tale of Princess Kaguya — the first film by Studio Ghibli auteur Isao Takahata in fourteen years, and likely his last — is not that each frame bursts with multitudes of details, but with barely the minimum. It is often as if the colors of the background are unfinished, every shot like a brief sketch than something meticulously worked over. In an era where anime films seem to blend into each other aesthetically, Takahata’s impressions seems marvelously alive — its modesty in images makes them feel as if they’re being created before our very eyes. – Peter Labuza

14. Shaun the Sheep Movie (Richard Starzak and Mark Burton)

Animation allows for exaggerated forms of action and expression that mean more can be said with complete silence than a traditional live action film can say in a whole monologue. The first animations were silent shorts, and Shaun the Sheep Movie embraces that tradition to create a moving, hilarious tale that plays just as clever and heartwarmingly to both children and adults. The tactile nature of the stop-motion lends the whole affair a warmth that most CGI can’t touch, and the care and time put into the designs of these characters alone deserve careful study from future animators. – Brian Roan

13. Ratatouille (Brad Bird and Jan Pinkava)

Arguably Pixar Animation’s most mature work (other than perhaps Inside Out) Brad Bird and Jan Pinkava‘s Ratatouille is a sumptuous celebration of creative zeal and gastronomical delight against all odds. Playfully toying with the perverse notion of a rat in the kitchen, Remy (Patton Oswalt) is a one-of-a-kind rodent, an autodidact culinary artist who finds himself in the Paris restaurant of legendary Chef Gusteau (Brad Garrett). After befriending Linguini (Lou Romano) a clumsy garbage boy who may be the rightful heir to the Gusteau dynasty, Remy must join forces with this hapless human in order to bring to life his unlikely dream of becoming a great chef. Produced during a time when Pixar’s affiliation with Disney temporarily lay on the verge of expiration, Ratatouille‘s stylishly sophisticated aesthetics remain a singularly unique and razor-sharp entry in the outfit’s lofty catalogue. The film is also a fleeting, but ambitious glimpse of the creative feast that could have been if Pixar managed to detach itself from that towering, mouse-eared monolith. – Tony Hinds

12. Boy & the World (Alê Abreu)

Crayon-like scribblings and simple geometric patterns meticulously complicate themselves like a fractal over the course of this child’s-eye odyssey through the global struggle between humankind and the forces that oppress it. Kaleidoscopic visuals use repetition to explore the communal nature of both work and celebration. This film continually pulls back to show the larger picture of society, its visuals becoming more complex in kind, before it reduces to a more intimate view in a supremely bittersweet rendition of Campbell’s heroic return. – Daniel Schindel

11. The Incredibles (Brad Bird)

The marriage of comic book narrative with animated feature filmmaking is so obviously a good idea that it’s a surprise that it hasn’t been done before. It’s especially surprising given how The Incredibles proves how effectively the form of the latter captures the spirit of the former. From kinetic and physics-defying action scenes that still sustain character and internal realism to exaggerated aesthetic choices that create a truly singular world for these actions beats to take place in, animation serves our heroes better than live action ever can. Pixar has done a lot of impressive things, but creating a super hero film so perfect that most people don’t even place it in the genre with the output of DC or Marvel might be their most subversively amazing feat yet. – Brian Roan

10. Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki)

The crown jewel of Hayao Miyazaki’s filmography — yes, better than My Neighbor Totoro — and the culmination of his pet themes of the struggles between purity and darkness, Spirited Away is almost a Yasujiro Ozu film, if Ozu ever made a film about an inn for ghosts, witches, and mystical spirits. That’s a slight jump, but Miyazaki shows a devout appreciation for the day-to-day processes of an inn — such as in a stunning sequence involving a hot bath — and an equally empathetic eye for how characters talk to each other, supernatural or otherwise. – Michael Snydel

9. Up (Pete Docter)

The married-life montage in Up is a self-contained masterpiece, a distillation of a lifetime’s worth of love and loss into a wordless four minutes. Stop the film there and you’ll have experienced more fulfillment than most movies can offer in their entireties. But continuing to watch brings greater joys still, as this early scene expands into an exuberantly old-fashioned yet novelty-filled adventure story and a tender portrait of the grieving process. Supplemented by impeccable animation (Carl Frederickson’s balloon-levitated house remains one of the wonders of modern CG artistry), Up is Pixar at its finest. It sends you into the clouds in more ways than one. – Jonah Jeng

8. Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud)

The critically acclaimed Persepolis is a young girl’s sincere coming-of-age story set against the violent backdrop of the Iranian revolution. It’s heartbreaking yet warmly funny, based on Marjane Satrapi‘s autobiographical graphic novel, which beautifully portrays the life of a woman grappling with the struggles of cultural identity. Rendered in a charming black-and-white color pallete, we see Marjane navigating the universal pitfalls of teenage life as she finds herself a terrified witness to the horrors of the ensuing revolution. It isn’t long before her home becomes too dangerous and her parents send her away to live a better life in Vienna. All the while, the guilt builds inside Marjane, who was spared a terrible and torturous fate that her family must still endure. Sobering and insightful, Persepolis is heartfelt proof that, as Marjane says, freedom has its price. – Tony Hinds

7. The Triplets of Belleville (Sylvain Chomet)

In an era when the bulk of CG-heavy output can carry an unfortunate dose of bland sameness, Sylvain Chomet crafts a strange, beautiful world with his masterfully clever debut The Triplets of Belleville. Mostly absent of dialogue, its in his opulently grotesque character designs where Chomet opens up the gateway to a much more eccentric story than your standard rescue mission. From one of cinema’s most iconic dogs to the Oscar-nominated song “Belleville Rendez-vous,” The Triplets of Belleville is brimming with memorable elements. While some may refer to it as a work of minimalism, I can’t name many more richly detailed creations in animation. – Jordan Raup

6. Millennium Actress (Satoshi Kon)

Cinematic history and personal memory merge in this tragicomic memoir of a lovelorn actress whose multiple roles stand as cyranoids of the many identities any person will cycle through over the course of their life. At the same time, the movie functions as a both a probe into the role of the female across various parts of Japanese filmmaking and as a loving homage to the industry. – Daniel Schindel

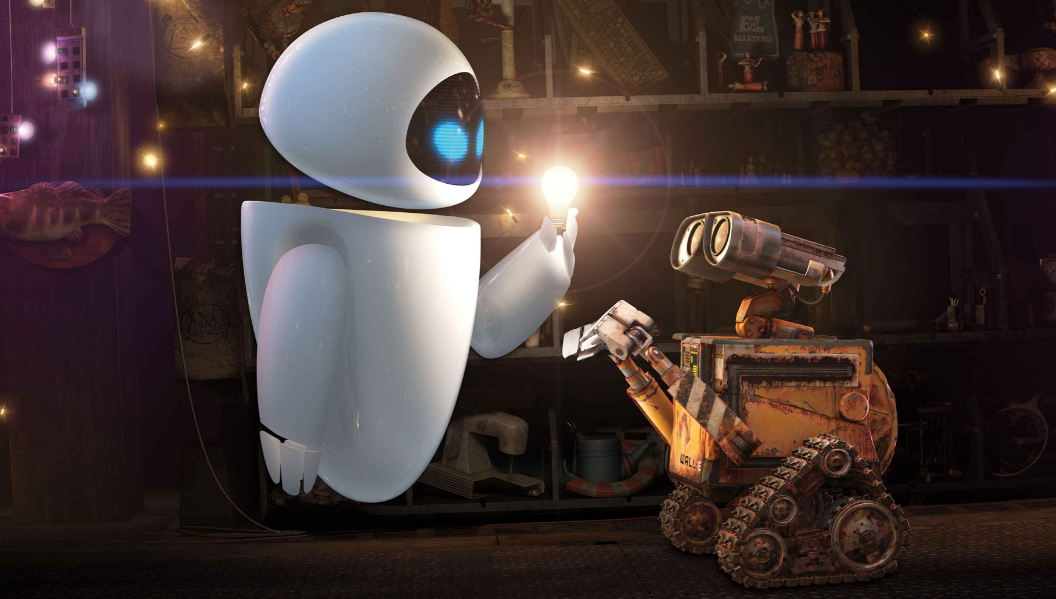

5. Wall-E (Andrew Stanton)

Going into Wall-E, I was informed that there would be very little words spoken through the beginning, but I didn’t know what to expect beyond that. What I wasn’t expecting was to fall in love with two robots because they were given a humanity that was enduring and a love story that stands among the best cinema has to offer. At its core, Wall-E is about finding a person or reason to live. You develop that over time, and hopefully it becomes more than just a single thing, but imagining it from the perspective of a singularly driven robot that breaks its protocol to follow its dreams? Transformative. This is peak Pixar and I’ll always adore the fact that they worked in geekery like Hal-2000, Sigourney Weaver’s voice (something to be repeated if you head to the theater this weekend), and the Apple Mac wake sound amidst a story of consumerism run rampant. It’s one of the best films to showcase both our awe-inspiring destructiveness in an effort to produce things while also creating technology that makes you gawk. Thank you, Andrew Stanton. – Bill Graham

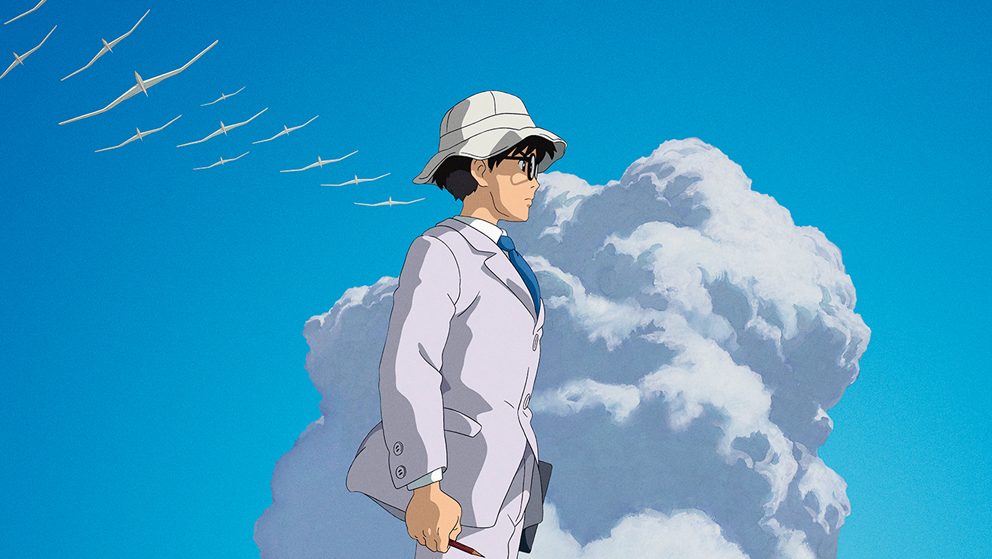

4. The Wind Rises (Hayao Miyazaki)

Hayao Miyazaki‘s final feature is also his most affecting work. With The Wind Rises, the director, aside from a few dream sequences, loses the fantastical elements his career has been built upon, and the result is an emotional connection I’ve rarely felt from animation. In tracking the life passions of Jirō Horikoshi, a man best known for designing the Zero Fighter plane used in bombing Pearl Harbor, it deals with obsession, guilt, and loss more effectively than any live-action film from its respective year. Although it’s only a few years old, I’m confident The Wind Rises will go down as one of cinema’s most graceful swan songs and a complex grappling with a difficult past. – Jordan Raup

3. Waltz with Bashir (Ari Folman)

Realism falls painfully short of reality in cases of trauma, where the meaning of objective, real-world events is shaped dramatically by the violence of subjective experience. In his novel The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien made a case for the telling of “story truth” in such instances, i.e. the implementation of artful distortions that ultimately convey the emotional reality of a past event more accurately than a direct retelling would. The quest for “story truth” underpins the groundbreaking aesthetic of Waltz With Bashir, a documentary composed almost entirely of animation. Here, the association between documentary and verisimilitude seems, at first glance, to have been unforgivably violated, but as dream, memory, and present-tense life converge around director Ari Folman’s attempts at salvaging truth from trauma, the film transcends many of its vérité counterparts in the reality it reaches. – Jonah Jeng

2. Fantastic Mr. Fox (Wes Anderson)

A perfect transition between artist and medium; a work existing between very perceptible reality and perfectly realized imagination; a constant generator of nostalgia and melancholy that doesn’t wallow, but moves forward towards something new without ever losing its feeling; and the oh-so-rare instance wherein Hollywood actors put their voice to film without stepping in the way of illusion. To put it in reductive terms: a cussing magical thing. – Nick Newman

1. It’s Such a Beautiful Day (Don Hertzfeldt)

Animated films get called “adult-friendly” as a means of both assuring adults the movie isn’t pitched too young and to let them know that some of the jokes will be over their children’s heads. If that is “adult-friendly,” then what should someone call It’s Such A Beautiful Day? Here is an avant-garde, mix-media animation that revolves around a man who is dying from some kind of degenerative brain condition. It follows him as he realizes the mundanity of the life he will leave, remembers the facts of his tragic existence, and comes to terms with what death holds. This isn’t adult-friendly — it is decidedly adult-oriented — but still not the type of things that most adults would want to see. It’s a profound, beautiful statement on mortality, and it is not friendly. Maybe we should call it “adult-antagonizing.” I am a proud champion of this genre, as well as its finest entry. – Brian Roan

Honorable mentions: A number of animations also nearly made the cut. We included Tomm Moore‘s latest film, but his previous The Secret of Kells is also worth seeking out, as well as the latest from Laika, The BoxTrolls. On the anime side, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence, Wolf Children, and Tekkonkinkreet are all recommended as are Studio Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There and From Up on Poppy Hill. On the Hollywood side, we were impressed by Rango, Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, and Tangled, but couldn’t find room for them here. Lastly, Hiroyuki Okiura‘s A Letter to Momo, the stop-motion oddity Toys in the Attic, and the Oscar-nominated A Cat in Paris and Chico & Rita will fill your animation fix.

What are your favorite animated films of the 21st century thus far?

See Also: The 50 Best Sci-Fi Films of the 21st Century Thus Far