We don’t want to overwhelm you, but while you’re catching up with our top 50 films of 2023, more cinematic greatness awaits in 2024. Ahead of our 100 most-anticipated films (all of which have yet to premiere), we’re highlighting 30 titles we’ve enjoyed on the festival circuit this last year that either have confirmed 2024 release dates or await a debut date from its distributor. There’s also a handful of films seeking distribution that we hope will arrive in the next 12 months, as can be seen here.

As an additional note, a number of 2023 films that had one-week qualifying runs will also get expanded releases in 2023, including Tótem (Jan. 26), Perfect Days (Feb. 7), The Taste of Things (Feb. 9), About Dry Grasses (Feb. 23), Shayda (March 1), La Chimera (March 29), and Robot Dreams.

The Settlers (Felipe Gálvez; Jan. 12)

The barbaric, bloody sins of the past come to define what entities govern certain land today, carried out by conquistadors and colonizers who hide behind righteous religious falsities to denigrate an indigenous population. With his directorial debut, a hauntingly conceived Chilean western The Settlers (Los Colonos), Felipe Gálvez localizes an origin story of this horror vis-a-vis the brutal genocide of the now-extinct Selk’nam people, who were native to the Patagonian region of southern Argentina and Chile. While spare early passages are narratively opaque and formally ornate to a distancing fault, the riveting second half––including a chilling reckoning with others occupying the desolate land and a well-executed structural gamble––brings profound expansion to this chilling story of atrocity.

Inshallah a Boy (Amjad Al Rasheed; Jan. 12)

In Inshallah a Boy, a new film from Jordan, a young mother faces some grueling events. It’s set around the bustling capitol, Amman, a place where temperatures are rarely low. One morning, Nawal (Mouna Hawa) goes to wake her husband but finds him lifeless. She soon learns she is set to inherit their house and his truck, but also four overdue payments for the vehicle. The money is owed to the man’s brother, Rifqi (Haitham Omari), who, benefiting from the country’s Sharia inheritance system, can also claim a slice of Nawal’s home. (Soon the man will believe he should inherit his brother’s daughter, too.) To make matters worse, it transpires that her husband hasn’t been working in weeks and Nawal’s income won’t come close to cutting it. Our hero has two options: sell the truck and pay the debt or convince them all that she’s pregnant with a boy. – Rory O. (full review)

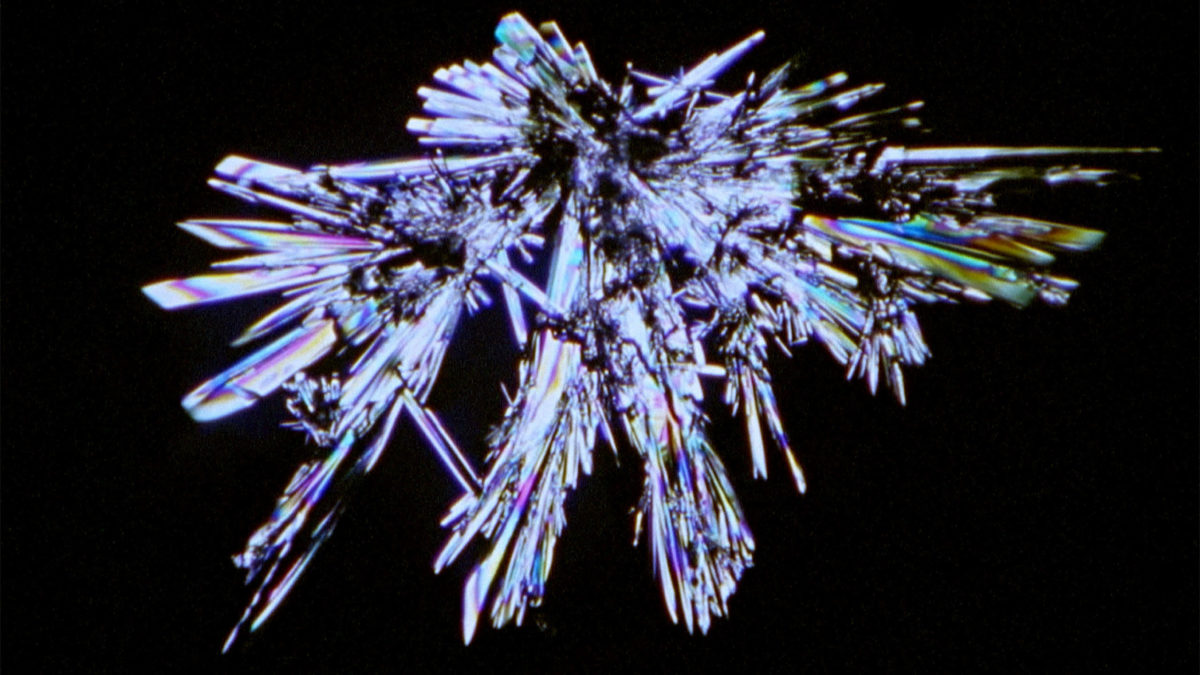

Last Things (Deborah Stratman; Jan. 12)

One of the best works to premiere at Sundance in 2023, Deborah Stratman’s Last Things explores the planet and our history through the point of view of rocks, and it’ll start a 35mm run at Anthology Film Archives next week. Fran Hoepfner said in her top 10 feature, “Despite its experimental nature, I believe that Last Things is––as best a thing can be––’for everyone.’ It is scary and mystical, funny and wholesome. It is both educational and profoundly entertaining.”

Apolonia, Apolonia (Lea Glob; Jan. 12)

Following, in intimate detail, the making of an art star in her early days, Lea Glob’s Apolonia, Apolonia is a powerful meditation on art and evolution. At one early point in the film, reflecting on a new work, Apolonia Sokol speaks directly to the camera, telling us that with “identity and work, there is no difference.” While some films about artists start capturing their subject much later in life, Glob’s picture is a work of serendipity, keeping praise largely in the moment. There are no talking heads or curators to provide context, just the filmmaker and Glob narrating most of the film with the tone of a bedtime story, as if she’s telling her daughter about this mythical time and figure in her life. – John F. (full review)

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (Phạm Thiên Ân; Jan. 19)

One of the most shocking debut features I saw this past year––in the sense that it was more accomplished than most other films of 2023––was that of Phạm Thiên Ân, whose Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell is an evocative, beautiful tale that will please fans of Bi Gan and Tsai Ming-liang. Winner of the Camera d’Or at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, as well as a TIFF and NYFF selection, the film––which follows an uncle searching for his long-lost brother while caring for his five-year-old nephew after his mother dies in an accident––opens in theaters this month. – Jordan R.

Pictures of Ghosts (Kleber Mendonça Filho; Jan. 26)

If the death of cinema is imminent, at least Kleber Mendonça Filho can play it out with some vintage Tropicália. It’s becoming a nice leitmotif of the Brazilian director’s career, whose ultraviolent Bacurau curtain-raised with Gal Costa’s “Não Identificado,” and latest effort Pictures of Ghosts, which premiered as a Special Screening at Cannes, eases in with Tom Zé’s deceptively jaunty “Happy End.” This is a first-person, arguably selfish movie––in that associated genre, the docu-essay––where Mendonça Filho seems to be waving a teary-eyed goodbye to valuable associations and possessions, perhaps only those of individual sentimental resonance. Yet it’s “selfish” in a productive manner, almost as a function of self-care, like a sunny afternoon lounging on the settee revisiting one’s favorite LPs. – David K. (full review)

Disco Boy (Giacomo Abbruzzese; Feb. 2)

To Disco Boy’s credit, while its core themes and imagery are second-hand, it does attempt to build, expand on, perhaps modernize Beau Travail, not unlike Helena Wittmann’s recent Human Flowers of Flesh, which premiered last year at Locarno (and actually featured Lavant playing an incarnation of his Galoup character). It’s also perhaps the first leading role of his glittering career to date where Franz Rogowski is miscast, feeling inappropriate or perhaps too worldly for the naive military grunt at the center; either way, the film’s debuting director Giacomo Abbruzzese attempts drawing out a performance that hits predictable notes of machismo, despair, and anguish. – David K. (full review)

How to Have Sex (Molly Manning Walker; Feb. 2)

Touching down in Heraklion, on the Greek island of Crete, marks the beginning of summer holidays for Tara (Mia McKenna-Bruce), Skye (Lara Peake), and Em (Enva Lewis), a trio of best friends who have just taken their A-levels and for whom school is the last thing on their mind. The first thing is… well, the title gives it away. British teens on holiday at a Greek resort means booze, booze, and more booze, but Molly Manning Walker’s debut film has the power to take these prosaic cultural archetypes (teenhood, virginity, youth drinking culture) and use them as tools to tell a poignant story about the ambivalences of growing up, female friendships, and consent. – Savina P. (full review)

The Promised Land (Nikolaj Arcel; Feb. 2)

After his 2012 film A Royal Affair received an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, Danish writer-director Nikolaj Arcel did what probably seemed logical at the time: go to Hollywood. But like many directors before him who walked that same path, the results were less than ideal––his being 2017’s disastrous Stephen King adaptation The Dark Tower. Six years later, Arcel returns to his home country and reunites with A Royal Affair star Mads Mikkelsen to make The Promised Land, a brutal, entertaining period piece and another showcase for Mikkelsen’s stone-faced magnetism. – C.J. P. (full review)

The Monk and the Gun (Pawo Choyning Dorji; Feb. 9)

Returning after his Oscar-nominated directorial debut Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom, Pawo Choyning Dorji’s IFSN Advocate Award-shortlisted The Monk and the Gun premiered at Telluride and TIFF to much acclaim and will now be released in February. Selected by Bhutan as their Oscar entry, the heartwarming film is about an American in search of a long-lost, vintage gun in Bhutan as they are in the midst of launching a democracy.

Here (Bas Devos; Feb. 9)

For anyone keeping tabs on Bas Devos’ career, it’s notable that the drama of his latest film Here is set in motion by something as benign as a pot of soup. A charming portrait with a flânuerial spirit, the film follows a Brussels-based Romanian construction worker who, having decided to move home, cooks what’s left in his fridge, packages it up, then gifts it to family, friends and––much later––a Belgian-Chinese woman doing a PhD in moss. She is played by Liyo Gang and he is played by Stefan Gota. It’s 81 minutes long, has relatively little dialogue, and tugs the heartstrings in all the best ways. It might be the most benevolent film of this year. – Rory O. (full review)

Out of Darkness (Andrew Cumming; Feb. 9)

Andrew Cumming’s gripping paleolithic-set survival horror is much more than it seems. What starts as a typical last-man-standing monster movie quickly upends expectations by rebuffing familiar beats. The score, courtesy Adam Janota Bzowski, is incredible. It crawls into your bones and sends shivers of prehistoric fear down your spine. Over a tight 87 minutes, the story incrementally shifts into new territory that’s not often portrayed on film––territory that forces us to reckon with the reality of our species’ pitch-black evolutionary past. Re: spoilers, stay in the dark if you can. – Luke H.

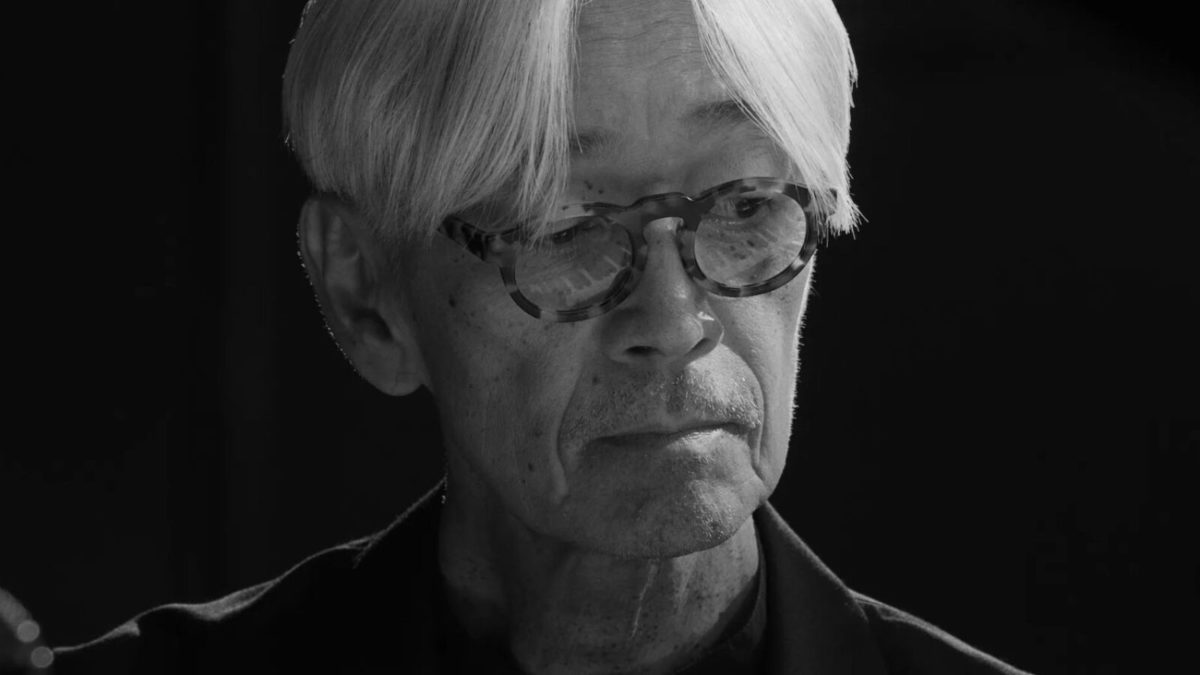

Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus (Neo Sora; March 15)

In a heartbreaking work that feels like a private personal home movie that the world is being graced with, Ryuichi Sakamoto’s son, filmmaker Neo Sora, captured one of his father’s final performances. Shot in beautifully austere black-and-white, Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus focuses solely on the music, capturing a man contending with his physical limitations in what amounts to one of the final offerings of his astounding talent. It’s a treasure. – Jordan R.

Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World (Radu Jude; March 22)

Long before the formal somersaulting of his 2021 Berlinale winner Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, the Romanian director’s films have hopscotched across genres and tones, weaving together the vernaculars of essay films, documentaries, and archives into projects that unfurl like mosaics. Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World follows in their footsteps. A collage perched between road movie and black comedy, Jude’s latest is another effervescent study of life in the 21st century, a work that’s engineered to both sponge something of our screens-infested zeitgeist and interrogate its textures. Few filmmakers are so reliably able to conjure snapshots of modern capitalism and its neuroses; fewer still can douse those documents with so much playfulness and wonder as Jude. – Leonardo G. (full review)

The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed (Joanna Arnow; April 26)

In The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed, Ann, a lugubrious New Yorker, sleepwalks through her daily life––colorless job, perennially disappointed parents––while maintaining a long-term sub/dom relationship with an older man. She visits her Jewish family, goes to yoga, and attempts some Internet dating. Invariably she winds up in her boyfriend’s lifeless brownstone. Executive-produced by Sean Baker, this is the feature debut of writer-director Joanna Arnow, a Brooklyn-based actor and filmmaker who made a name for herself as a wry observer of millennial sex lives and stasis with a couple of award-winning shorts: Bad at Dancing (2015) and Laying Out (2019). In Dancing, Arnow sat naked on the floor, casually asking for advice from a friend having sex right in front of her. The sense that everyone around you is getting their shit together (and maybe getting laid) is present again here; yet eight years hence, it arrives with the added humility of lived experience. – Rory O. (full review)

The Beast (Bertrand Bonello; Spring TBA)

Where to begin with Bertrand Bonello’s wonderful The Beast? It’s been so gratifying to see the initial reaction to the French filmmaker’s tenth feature, after several decades of increasingly remarkable work––the majority of it dark, beautiful, and sleazy. In fact, for what a discomforting and despairing experience much of The Beast is, when I’ve thought back its moments of real, uncomplicated cinematic pleasure, its verve and sense of joyousness, are what mark my memories. It’s romantic, without a capital-R. – David K. (full review)

Evil Does Not Exist (Ryusuke Hamaguchi)

Amongst a typically raucous lineup at this year’s Venice Film Festival comes Evil Does Not Exist, a work in which tensions rise over little more than the placement of a septic tank. It’s the latest from director Ryusuke Hamaguchi and his first since 2021’s miraculous double-punch of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy and Drive My Car. Evil concerns a clash of urban and rural sensibilities: a story about a small but hardy group of people who wish to stop the development of a glamping site. Devotees of Kelly Reichardt’s sylvan melancholies will feel perfectly at home. – Rory O. (full review)

Gasoline Rainbow (Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross)

“The only difference between children and grown-ups is that the grown-ups are unsupervised.” This line, uttered in the second half of Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross’s seventh feature Gasoline Rainbow, is not particularly framed as words of wisdom. The award-winning filmmakers have explored American life through places, people, and their interconnectedness since the late 2000s in a way that’s far from linear. A multitude of voices, characters (or simply people) populate the screen, their practice exploratory before it aims at any definitive answers. The why and the why-not are irrelevant questions, yet every new offering feels as profound as life itself. Gasoline Rainbow, a premiere in this year’s Venice Orizzonti sidebar, benefits from their trademark hybrid filmmaking, placing nonprofessional teenage actors on a thrilling 513-mile journey from Wiley, Oregon, to the Pacific Ocean. – Savina P. (full review)

Green Border (Agnieszka Holland)

Before the New York Film Festival premiere of her latest opus, Green Border, legendary director Agnieszka Holland wished everyone a good screening: “I would tell you to enjoy the film, but that would not be appropriate.” It was an apt warning for the harrowing, exquisite film that unfolded. Green Border focuses on the treatment of migrants trying to cross from Belarus to Poland so they can find asylum in the European Union. As a result, Holland is now on the shit list of nearly every high-ranking Polish politician, from the president to the Minister of Science and Higher Education. What a shame they’re so blinded by their station that they can’t even appreciate magnificent works of art. Green Border is a riveting, finely crafted, deeply human accounting of the atrocities we make permissible in the name of nationalism. – Lena W. (full review)

His Three Daughters (Azazel Jacobs)

Absence is at the center of His Three Daughters, Azazel Jacobs’ latest film. It’s set almost entirely in a small New York City apartment as three sisters reunite to care for their ailing father in his final days, and Jacobs never lets us see inside his room. The camera stays largely in common areas where the three leads argue, cry, reconcile, and come to terms with living in a world where the one thing tying them together no longer exists. Barring some divisive final-act choices, it’s a powerful work with a smart screenplay and three terrific performances that capture the messy nature of families going through a grieving process. – C.J. P. (full review)

Hit Man (Richard Linklater)

What Hit Man lacks in technical craft, it compensates for in allure, the most organically sexy movie you’ll see this year. Almost too sexy at times (this is not a problem). As in: there’s no way you watch this with someone you’re into and get through more than 20 minutes without pausing or abandoning it for another night (or another; it might take a few tries). That’s one of the strengths in hiring two of the hottest people on the planet. – Luke H. (full review)

The Human Surge 3 (Eduardo Williams)

The Human Surge 3, Williams’ second feature and follow-up to his 2016 The Human Surge (the first installment of a trilogy with no second chapter), is another stupefying project designed to push the medium toward new, uncharted paths. Like the first Surge, this too unfurls in its barest terms as a hangout movie, cartwheeling across three different countries (Sri Lanka, Peru, and Taiwan) to dog a few low-income twenty-somethings as they fritter away time with friends in-between odd jobs. But where the saga’s first episode played like three shorts stitched together, traveling across distinct settings in standalone segments, The Human Surge 3 trades that for something far more elliptical and confounding. The youngsters at its center––Meera and Sharika, Livia and Abel, and Ri Ri and “BK”––aren’t confined to their respective countries but keep showing up in each other’s locales, and the film itself seems to exist in a multiverse that collapses time and space; one minute we’re roaming the rain-soaked slums of Iquitos, the next we’re strolling past Sri Lanka’s igloo-shaped, anti-tsunami houses. – Leo G. (full review)

In Our Day (Hong Sangsoo)

Like other Hong Sang-soo films, In Our Day passes, on the surface, for simple fare. The prolific South Korean director layers weighty themes amidst naturalistic filmmaking, almost documentary-style in his willingness to let the camera sit without needing any extra flourishes. Cutting between two scenes––both playing out over a single afternoon––Hong focuses his energy on the dialogue between his characters, on the rapid intergenerational misconceptions. In doing so he muses on the pessimism of art, the somewhat meaningless nature of life, and how we interpret the actions and words of our fictional heroes. – Michael F. (full review)

Janet Planet (Annie Baker)

About halfway through playwright Annie Baker’s self-assured and pitch-perfect directorial debut Janet Planet, 11-year-old Lacy (Zoe Ziegler) rolls over in bed and turns to her mother Janet (Julianne Nicholson) with an innocent prompt. “You know what’s funny?” she asks. “Every moment of my life is hell.” At such a gentle moment, in such a casual way, she delivers a melodramatic gut-punch. You can’t help choking out a laugh. – Jake K-S. (full review)

Last Summer (Catherine Breillat)

Anne (Léa Drucker) is an esteemed lawyer: as uncompromising as she is in her line of work, she is free to enjoy her private life. In her ’40s she has it all, the job and the family she never thought would come. So begins Catherine Breillat’s newest film, Last Summer, which may be a remake of May el-Toukhy’s 2019 adulterous drama Queen of Hearts, but yields to the French filmmaker’s every wish. Even though we never get any backstory to Anne’s character, it’s hinted that her youth was not a pleasant one, as an early abortion took away the possibility to have children of her own. But now, in the summer of her life, she is a mother of two adopted girls and stepmother to an unruly teenager named Théo (Samuel Kircher), from her husband Pierre’s (Olivier Rabourdin) previous marriage. Amidst the idyllic rituals of daily life in the countryside, Anne seems composed and satiated. She is not one to look for trouble. – Savina P. (full review)

Music (Angela Schanelec)

Thirty or so minutes into Angela Schanelec’s Music, a character makes a startling discovery. We’re inside a prison on the outskirts of an unidentified Greek town, where Jon (Aliocha Schneider) is to spend a manslaughter sentence. And we’re watching him bathed in the cell’s cold light when he suddenly opens his mouth and starts to sing. It’s a moment that shatters the film, one of the loudest in a tale otherwise marked by wistful silences. Jon’s stuck a grocery list of classical composers to the wall, and he intones an aria from Vivaldi’s Il Giustino, “Vedrò con mio diletto.” It’s the first time we hear him sing and it amounts to an otherworldly revelation, both for the young man crooning and those of us who listen: a human being waking up to a superpower. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Petrol (Alena Lodkina)

Upending familiar territory for an emerging director––i.e. making a film about an emerging director––Alena Lodkin’s Petrol is an enchanting inquiry into performance, creativity, and the struggles of collaboration. With a firm grasp on evocative film grammar, there’s not a single frame or cut that feels like an afterthought, leading to a captivating atmosphere as fantastical flourishes pop into the world of film student Eva (Nathalie Morris). For making a fitting double feature with James Vaughan’s similarly lo-fi, charming Friends and Strangers, there’s certainly something promising brewing in the Aussie indie film scene. (Also, bonus points to Lodkin for nailing the film-student trope of not recognizing Spielberg’s greatness until well past graduation.) – Jordan R.

Problemista (Julio Torres)

The term “unique voice” gets thrown around a lot. But how else do you describe Julio Torres? Over several years as a writer for Saturday Night Live and actor on HBO’s Los Espookys he’s quietly cultivated his own fresh, distinguished comedic sensibility, highlighting the surreality and humanity in the perfunctory. That’s most evident in the variety of digital shorts written during his time at 30 Rock, where he captured, for example, the nightmares and paranoia of a graphic designer tortured by Avatar’s papyrus font, or the inner life of an oddly shaped glass sink in an otherwise bland linoleum bathroom. You picture him looking at the world with his head slightly bent. – Jake K-S. (full review)

The Shadowless Tower (Zhang Lu)

Watching over Beijing’s Xicheng district is an enormous white pagoda, a relic of the Kublai Khan rule, so majestic and otherworldly in looks and stature it might as well have been dropped on Earth from a far-flung planet. Legend has it the monument casts no shadow––not in its immediate vicinity, at least––though its silhouette is said to stretch as far as Tibet. No other corner of the megalopolis features as prominently as this one in Zhang Lu’s The Shadowless Tower, a film to which the 13th-century wonder lends its title as well as a metaphor for the kind of permanence its drifters fumble after. And no one among them is as drawn to it as Gu Wentong (Xin Baiqing). – Leonardo G. (full review)

Sing Sing (Greg Kwedar)

“We are here to become human again.” This is the mantra of the Rehabilitation Through the Arts program, founded in Sing Sing Correctional Facility, a prison just north of New York City, and the subject of Greg Kwedar’s emotionally restorative new feature. While led by a stellar Colman Domingo with an equally great supporting turn from Paul Raci, the majority of Sing Sing‘s cast knows the program all too well, either as alumni or currently going through it. That authenticity in casting carries through every frame and every line, as if Kwedar has walked these halls and been in these rooms, an observer to the intimate conversations he’s scripted alongside Clint Bentley. – Jordan R. (full review)

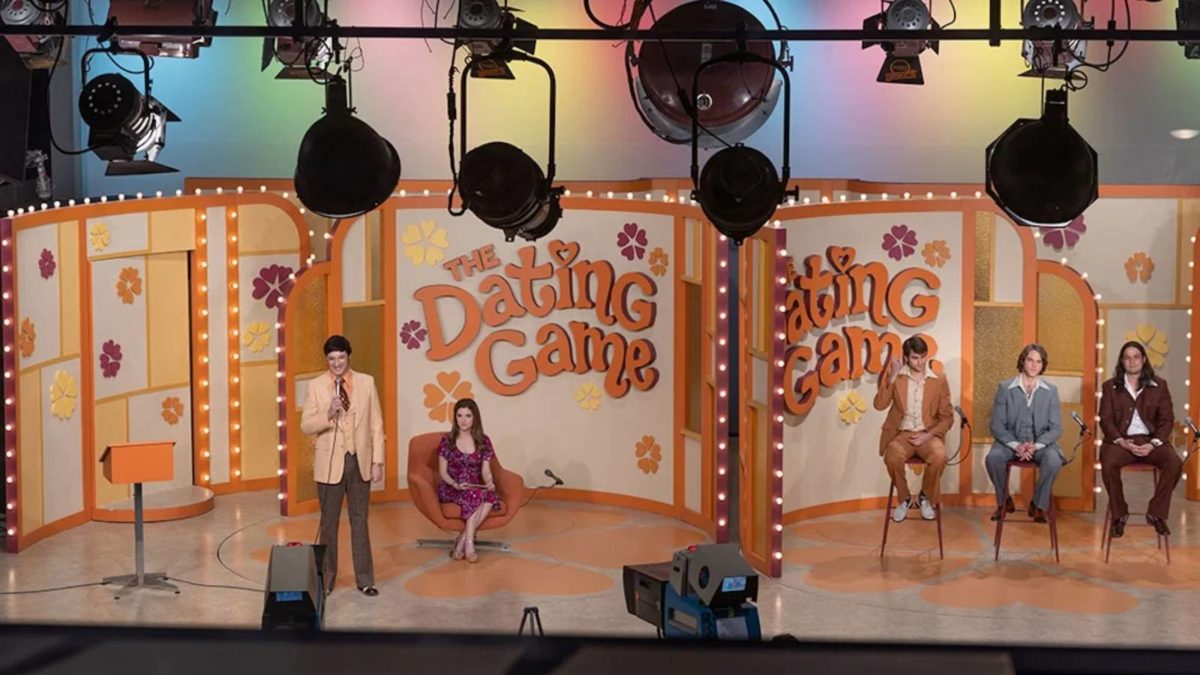

Woman of the Hour (Anna Kendrick)

The logline of a serial killer and rapist taking part in a television dating game show sounds like a high-concept pitch so fabricated it couldn’t possibly be founded in any veracity. Yet, in 1979, Rodney Alcala––whose victims are believed to be as many as 130––was a bachelor on The Dating Game. For her directorial debut, Anna Kendrick expands the 30 minutes of airtime into an inquiry of misogyny and the everyday silencing of women, exploring both Alcala’s shocking murders and the story of a fledging actress hoping for a big break. With a careful threading of humor and horror, it’s an ambitious, slightly strained gamble that Kendrick mostly manages with a formally precise vision and script that doesn’t rely on platitudes. – Jordan R. (full review)

More 2024 Releases to Have on Your Radar

- The Breaking Ice (Jan. 19)

- Sometimes I Think About Dying (Jan. 26)

- Mambar Pierrette (Jan. 26)

- Dario Argento Panico (Feb. 2)

- She Is Conann (Feb. 2)

- Skin Deep (Feb. 2)

- Ennio (Feb. 9)

- Drift (Feb. 9)

- Io Capitano (Feb. 23)

- On the Adamant (March 15)

- Riddle of Fire (March 22)

- Club Zero (March 22)

- The People’s Joker (April 5)

- Kill

- Man in Black

- Merchant Ivory

- A Prine

- Sleep

- Slow

- The Social Realism