Martha Stephens’ Pilgrim Song takes place, as many a SXSW 2012 film did, in the woods. James (Timothy Motton) is a music teacher recently let go due to budget cuts. The school’s principal offers him a summer teaching position which he rejects instead taking to the hills of Sheltowee Trace trail in Appalachian Kentucky. He’s married, although his wife Joan (Karrie Crouse) who is somewhat slow, helps him pack and keeps in radio (well, iPhone) contact, but does not join him on this journey. Much is left unspoken early in the relationship – Joan still has a job in a whisky distillery – perhaps they both require a break from each other as much as James requires this break from the “real world” instead of teaching summer school.

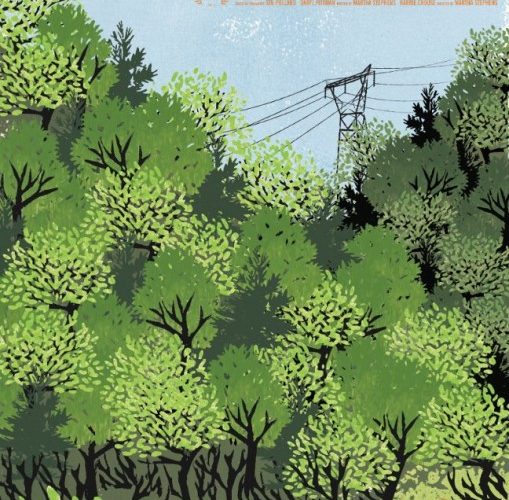

James was once a somewhat famous musician, he joins a jam one night and is seduced by a beautiful and mysterious women. Pilgrim Song, as its name implies is the stuff of a backwater bluegrass blues. The pacing is slow and at times a tad tedious to a fault (consider what would be the film’s second act, if the film has a five act structure – beautiful but endless shots of hiking create a rhythm while lacking the exposition of the first act which we can consider “life in civilization”). With this, Pilgrim Song is Antonioni by way of early David Gordon Green.

James was once a somewhat famous musician, he joins a jam one night and is seduced by a beautiful and mysterious women. Pilgrim Song, as its name implies is the stuff of a backwater bluegrass blues. The pacing is slow and at times a tad tedious to a fault (consider what would be the film’s second act, if the film has a five act structure – beautiful but endless shots of hiking create a rhythm while lacking the exposition of the first act which we can consider “life in civilization”). With this, Pilgrim Song is Antonioni by way of early David Gordon Green.

Along the way James encounters several colorful characters suggesting an ethnographic take on this journey, and by way of his music is an unintentional anthropologist, finding himself collecting stories for inspiration. On this spiritual quest James meets a pot-smoking retired park ranger (Earl Lynn Nelson) keeping watch over a hill and a father and son (Bryan Marshall and Harrison Cole) who become his guide, at least for his return journey.

Sparse in its use of space, Pilgrim Song is as simple and humble a film as its on-screen journey with strong performances by Morton and Crouse (who co-wrote the screenplay with director Stephens). The film archives an honesty and sincerity in its simplicity and emotions. Consider the early departure scene, which contains much silence, a little hesitation and ultimately freedom, it is beautifully acted. While the film should exists within its own context, where I fault it (rather unfairly) is that certain moments become tedious, especially within the context of films programmed this year at SXSW, which also feature characters between 20-40 entering the woods. Lyrical and poetic, when it works, it works. When it doesn’t, we are stuck until the next beautifully drawn moment; the rhythm of this song is just slightly off.