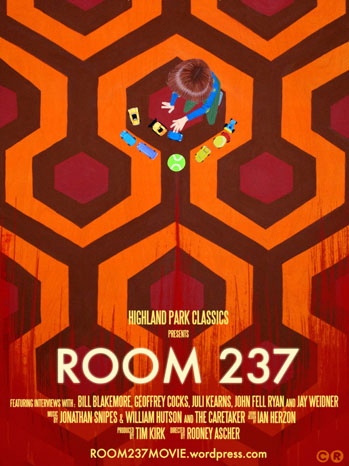

For many fans of cinema, Stanley Kubrick is revered as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, notorious for his intellectual obsessions and attention to detail. In Rodney Ascher‘s documentary Room 237, the filmmaker assembles a group of obsessed Kubrick loyalists to carefully examine, frame by frame, some of the hidden messages behind his controversial 1980 film The Shining. Oddly enough all the interviews are audio only. Instead of focusing on the people offering up analysis, the viewer can focus on the cinematic evidence they are presented with. Using footage from The Shining and other Kubrick films, along with some moments from his daughters making-of documentary and scenes from other random yet popular movies, Ascher visually deconstructs anything that could be of relevance.

The film is broken down into nine segments, each chapter focusing on a different specific element of The Shining that may reveal hidden clues and hint at at a bigger thematic oeuvre. These range from background art decor of Native Americans and symbols referencing Nazi Germany to camera movement and long dissolves creating subliminal illusions with subtle image juxtaposition. It’s the type of thing you would only notice after obsessively re-watching a film scene by scene, moment by moment, for any peculiarities that might jump out. Some examples go even farther, from mapping out the geography of the hotel to carefully dissecting the bike pattern that young Danny follows. For the die hard fans it’s all very fascinating and extremely revelatory to show potential methods Kubrick was using to subtly manipulate the audience.

There is a sizable amount of validity to the arguments presented despite the fact that some of the rationale behind certain theories seems like a stretch. One speaker in particular raises a conspiracy theorist style claim that Kubrick assisted in forging the moon landings using the front projection technique he employed in 2001. Another questionable claim is that in the opening credit roll Kubrick superimposed an image of himself into the clouds, which even in slow motion was impossible to detect. Still, the possibilities of all these hidden gems hiding in plain sight gives motivation to revisit more of Kubrick films for similar in-depth analysis.

The one unfortunate problem with Room 237 is that it’s possibility for a commercial release is murky at best, and seeing it beyond the festival circuit might be impossible. The reason being is that majority of clips are being used under fair use, so in a commercial setting the Kubrick estate along with Warner Brothers will most likely attempt to block public screenings. At times the film feels like it would be best suited for the Internet and even the style of filmmaking feels apropos to similar commentary found on YouTube. Hopefully for the true fans of Kubrick who continue to obsess over his films, Room 237 will come to light and illuminate the idiosyncratic obsessions of one of the greatest auteurs.