The Austin based Zellner brothers are known for their particular brand of off-beat dead-pan humor and eccentric worldview. With their new film Kid-Thing the duo continue this tradition with a quiet fable about a restless young girl who has an endless appetite, setting out to do bad things. Shot in a rural part of Texas, they employ a simplistic style, with scenes often comprised of carefully composed static shots. It lends itself to a particular brand of subdued cinema where nothing much happens and the smaller nuances are supposed to keep you interested. Depending on how much you enjoy this subtle variation in genre will effect how much you read into the parable, but Kid-Thing still does little to nothing that makes all the waiting worthwhile.

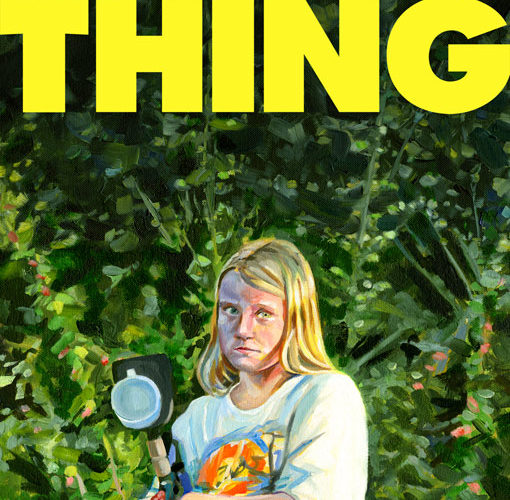

The main bulk of the film resides on the shoulders of a 10 year old girl Annie (Sydney Aguirre) who has a void in her life where there should be an authoritative parent. Instead the rambunctious youth fills her days with rebellious activity living each moment without a care. Yet there is a sad loneliness that lingers with Annie as she goes about her routine of inflicting chaos, she is isolated by the world around her and lives constantly in her own introverted mind. This is exemplified perfectly by a scene in which she attempts to play at the local playground only to be rejected by the kids who view Annie as an outsider. It would seem that Annie has no one in her life to watch over her, especially since her hillbilly farmer dad (David Zellner) spends most of his time with his equally dull mud racing friend (Nathan Zellner).

That is until one day she stumbles upon a hole in the ground where she hears the voice of an older woman (Susan Tyrell) pleading for help. The identity of this mysterious person trapped below the surface adds forward momentum to the dull drum of Annie’s life. Is it a real person trapped down there, is it Satan incarnate or is the voice just a figment of a Annie’s imagination? As the mystery of the hole on the ground unravels at a snail’s pace, the straws of symbolism continue to unfurl but by the end none of it feels important. These existential questions are the only branches of substance the Zellner brothers hope to embody the film with, but it’s far from enough to keep things interesting.

Perhaps Kid-Thing would have been more effective if the story arch of the protagonist come full circle or if something substantial had happened to truly change the landscape. Instead most of the film meanders just as the central character does, with pretty landscapes juxtaposed by rotten carcasses artificially designed to shock you. In many ways this pointless tone feels like a tamer version of Harmony Korine’s Gummo while comparisons to Terrence Malick‘s Days of Heaven are wildly misleading and more ego-inflating than genuine. If Kid-Thing represents a new breed of brooding American cinema, then I hope more inventive examples are in store for the future.