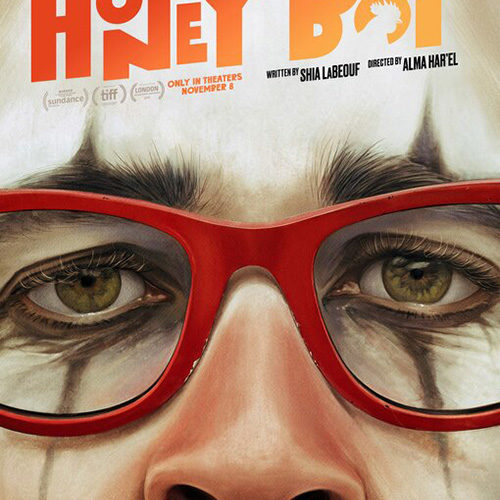

Following sci-fi sound effects over the opening credits on a black screen, Honey Boy begins with a hard cut on the face of Lucas Hedges as he’s pulled back on a harness on the 2005 set of a blockbuster. A clear nod to the Transformers franchise, we then rapidly run through multiple on-set experiences that blend into an alcohol-induced car accident. This opening, however, is not an indication of where we’re headed. Written by Shia LaBeouf, Honey Boy could have easily been a satire of his much-publicized last decade, with his headline-making performance act and legal troubles. To the film’s benefit, LaBeouf and director Alma Har’el rather go much more in-depth (and farther back), taking a deep-rooted look into the actor’s traumatic childhood. Whether intentionally intended or not, this earnest endeavor does wonders to enact sympathy and overturn any negative public perception of his outbursts, even if it can feel more like self-therapy than a fully-formed film.

Otis is the Shia LaBeouf surrogate, played in 2005 by Hedges and in 1995 by a stand-out Noah Jupe. When we’re introduced to the younger Otis he’s also flung back in a harness, mirroring how we meet the older Otis, but this time shooting a pie-in-the-face gag. It’s an immediately clever visual touch to show how the level of stardom for LaBeouf (er, Otis) may have expanded, but the game is still the same. Not only writing the script, LaBeouf takes things to an overtly meta level by playing Otis’ father James, a balding, womanizing Vietnam War veteran who takes out his many personal demons on his son through verbal and physical abuse. From insults about his “Jew riblet penis” to actually slapping him, James believes he’s building Otis up with strength. As he lashes out and prods his son for needless reasons, LaBeouf so consumes the nuances of the role that it feels like he’s been waiting his whole adult life for the right time to go through the cathartic experience of making the film.

Jupe is fantastic as the 12-year-old Otis, shouldering with a too-young level of maturity the increasingly maniacal insults and demands of his father, whose present for him is a pack of cigarettes, which he must smoke in the bathroom as to not have the public perception of being a “shit father.” His mother is only heard in an equal parts heartbreaking and humorous scene, where he must relay his parents’ fight over the phone as they both shout at him. She has a job just in case Otis “fails,” his father tells him in a jab. Considering the child actor is the one making the money in the family, he’s in fact his father’s boss and their push-pull dynamic is a compelling one to behold. The meta aspect of LaBeouf (the actor) tearing apart his own child while he is no doubt racing through his own past in preparation and execution for the role is the film’s greatest success, and Honey Boy would likely be far less engaging if this layer of a personal recking with the past was stripped away.

The only time spent with the older Hedges is in therapy, with visions of his traumatic upbringing haunting him daily, often serving as fitting (if overly obvious) transitions between the two time periods. An otherwise under-used Hedges most excels during intense one-on-one therapy sessions, even mimicking mannerisms we’ve seen from LaBeouf. The older Otis self-diagnoses himself as an “egomaniac with an inferiority complex,” with these lines having a further edge of self-confession coming from LaBeouf himself. The casting of Hedges also has subversively perceptive touch as we’ve seen the actor take a different career path since his break-out, focusing more on the dramatic material LaBeouf now seems to be most interested.

Rather than a self-serving retelling of the past, Har’el imbues this journey with a messy, humanistic beauty, just as she did in her last film, the documentary LoveTrue. It’s rare for a film to feel so unshakably co-authored by its writer, but it is to LaBeouf’s credit that, after being impressed by her first film Bombay Beach, he brought on Har’el to give a graceful vision to this story. Shot by The Neon Demon cinematographer Natasha Braier, she feels at home in the warm California landscape, bringing a feeling of almost magical realism to certain sequences, particularly when it comes Otis’ relationship with a local prostitute (FKA Twigs) that lives across from their motel. Their connection blurs the line between a motherly figure and his first sexual encounter, but this arc feels woefully underdeveloped in comparison to the well-articulated chaos that is the central father-son thread.

As someone who often found genuine artistry in LaBeouf’s recent antics, it’s often riveting to see him take a more inward, meta focus here. A role such as this requires a painful confrontation with the past and the actor-writer is clearly getting a significant cleansing out of blurring the thin line between reality and fiction. The next time we see a young star unravel in the public eye, Honey Boy argues we should dig a bit deeper before the world revels in their troubles.

Honey Boy premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and opens on November 8.