One of the most succinct, yet heavily weighted lines of dialogue in cinema history is a three-syllable call to death: “Time to die,” as Rutger Hauer’s Roy Batty commands Deckard in Blade Runner. Hawaiian filmmaker Christopher Makoto Yogi’s I Was a Simple Man makes its own attempt at this profundity, attempting to sum up the big goodbye in one epigrammatic phrase. “Dying isn’t simple is it?” is spoken––murmured gently, more like––no less than three times across the film, and by the end, Yogi’s work seems to have offered a resolution to that question, although viewers may beg to differ.

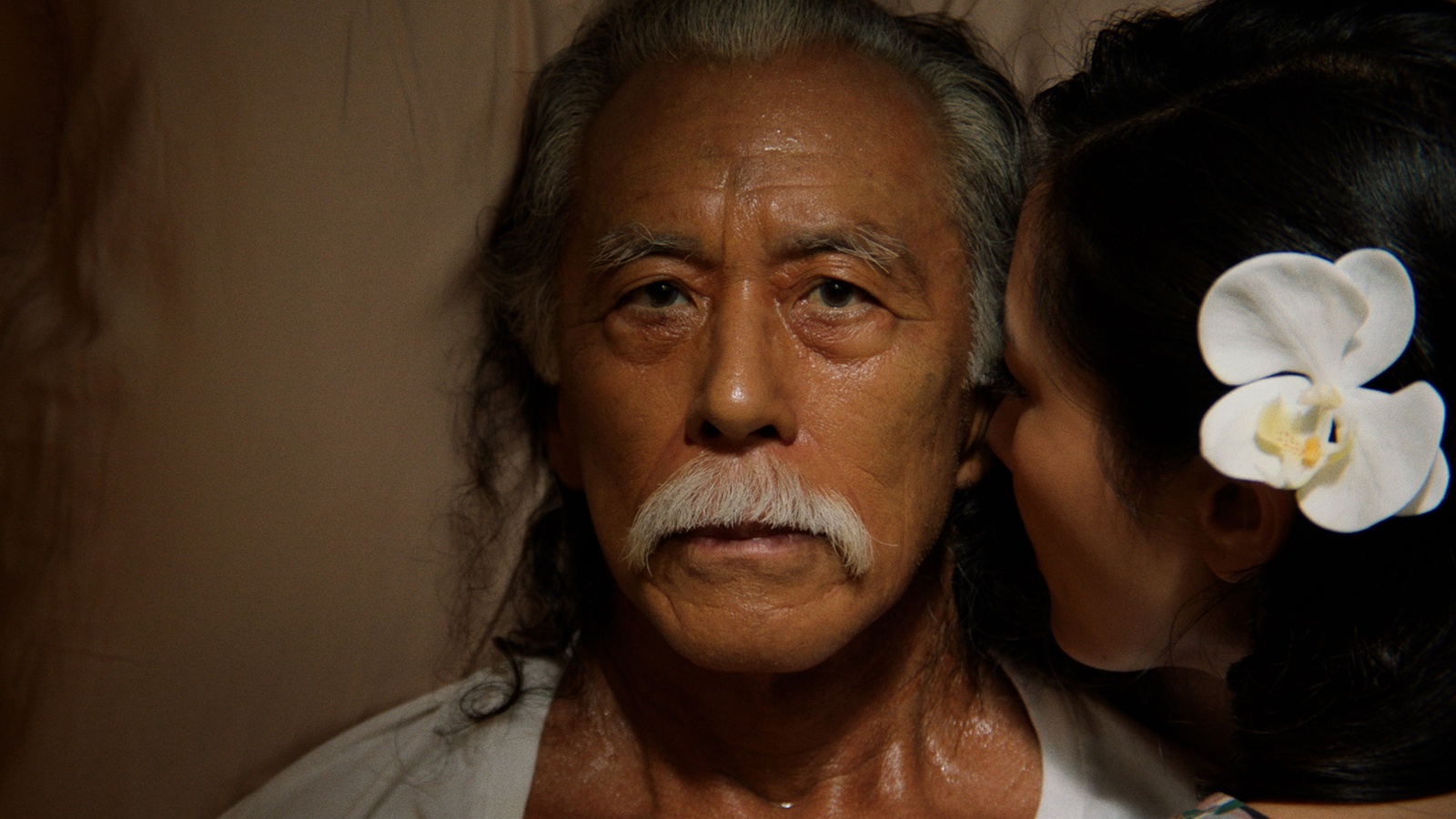

Ah, death. You can’t stop what’s coming, and equally, you can’t stop art film directors conjuring up all their poetic means to give this subject its due. Yogi has switched tack for his second feature, his first to premiere in the U.S. indie big leagues at Sundance. His debut August at Akiko’s examined a young Hawaiian-born free jazz saxophonist’s lazy summer, as he returned to his family’s place of origin; shot in brimming, sun-baked daylight, it was a film with anything but mortality on its mind. I Was a Simple Man takes us to the very opposite end of the spectrum, chaperoning us through the bedridden soul-searching of Masao, a cancer-stricken resident of Oahu (on the island’s north shore) looking for some peace at the end of his troubled life.

Yogi himself has been vocal about his admiration for slow cinema greats such as Tsai Ming-liang, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Naomi Kawase, and partisans of this film have felt his work here––laden as it is with observational long takes and ghostly, foggy atmosphere––earns comparisons with them. For me, I Was a Simple Man evoked these touchstones in the most nominal of senses, guiding us through a coherent story more purposefully, where any non-linear confusions are resolved neatly at the close; at times it’s like a newspaper obituary or a funeral eulogy written in free verse. The way figures from Masao’s past, most noticeably Constance Wu in a role as his deceased wife Grace, congregate around his bedside, and interact with him beyond their lifespans, reminded me more of Roy Scheider’s hallucinatory death in All That Jazz.

This is evidently a personal, deeply felt work for its creator, one that tries to impart the real essence of Hawaii beyond the touristic manner it’s often depicted. Hawaii only officially joined the United States in 1959, and although its status as an American incorporated territory lasted across the whole 20th century, Yogi sees the admission to the union in starkly symbolic terms. Depicted in a lengthy flashback sequence, Masao’s wife Grace dies on August 21, 1959, the very date the Admission Act was signed, asserting a break both in Masao’s heart, and in Hawaii’s identity, that can’t be sewn. This is complicated by what their Asian identities––Japanese and Chinese, respectively––meant in the initial post-war period: Grace’s family was scandalized by her daughter courting a citizen of their wartime enemy. And Masao himself felt unable to fulfil his role as a father after bereavement, leaving his three children to live permanently with a relative.

Two of his grown-up brood, Kati (Chanel Akiko Hirai) and Mark (Nelson Lee) must now attend to their father in his final days. They potter well-meaningly around him, but Masao is so impassive to their love and attention as to appear suffering from mild dementia as well as his terminal condition. He wades through the spirit world, gazing at younger versions of himself and Grace roaming the same physical space as him, but flashback-driven explanations are found as easily as clicking on hyperlinks.

I Was a Simple Man premiered at Sundance Film Festival.