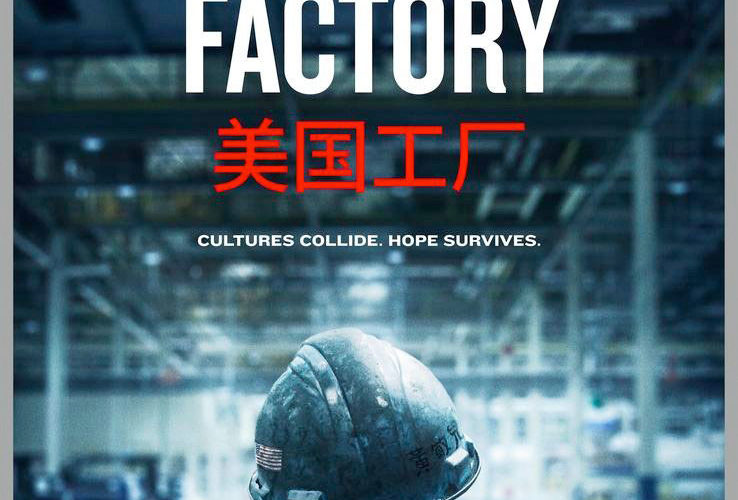

When the Rust Belt was hit hard in the financial crisis of 2008, the blue-collar workers of Dayton, Ohio found a savior in a Chinese billionaire. Six years after the lifeblood that was a General Motors plant was shut down, the car-glass manufacturers Fuyao opened up their first American factory in the town, meaning thousands of new job opportunities. The promise of a steady income lifts the spirits of the workers, but an East vs. West clash of working methods quickly emerges, causing labor division, personal strife, and some unexpected camaraderie amongst the workforce. Directors Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert–who were Oscar-nominated for another look into the recession, The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant–capture this conflict in it all its complications, humor, and heartbreak in their thoroughly engrossing documentary American Factory.

To ease the transition from Chinese workflows to that of America, the company brings over hundred of workers to oversee the segue which doesn’t quite go as plan, to put it plainly. Initially beginning with humorous exchanges which could be construed as deleted scenes from a spin-off of The Office, a supervisor holds a training session for these Chinese transplants to better understand how to interact with Americans, highlighting their casualness in dress and how you can “say anything” around them, even joking about their President. In assessing their work ethic, Chinese workers even go on to say Americans are “slow” and “they have fat fingers.” This joking manner soon manifests into a stark difference in operating approaches that have grave effects on the workers, resulting in thousands of instances of employee turnover. “You know you are capable when you can train Americans to work on their own,” one Chinese worker says later in the film, flaunting their feelings of superiority.

Yet, CEO Cao Dewang’s aim in opening this plant is to “change America’s view of the Chinese” and how the two countries could work together. What soon surfaces is his insistence on not conforming to the ways our country. Introduced as a bull-headed, all-knowing leader, he prophesizes the weather won’t change when an expensive structural addition is needed to protect their product. His determination lies in efficiency and reaching a profit above all else, leading to lower wages, unsafe work environments, and a hostility towards the idea of unionizing.

These ideas get illuminated in a business trip that some of the American supervisors take to the main plant in China. In an image that describes the entire theme of American Factory in a nutshell, one of the American workers wears a Jaws t-shirt when going to a board meeting with the Chinese supervisors, all of which are wearing finely-tailored suits. While at the plant, the see the communist influence in the workforce as they often work 12 hours a day and only get 1 or 2 days off a month. As Dewang puts its, the point of life is the work you get out of it and this idea is so deeply ingrained in every part of their routine. From “meetings” that are more like structured military chants to a lavish year-end New Year’s party that has propagandistic performances about how to be more efficient at work, it’s an eye-opening experience for blue-collar workers. Before they go on stage to do YMCA–a nice real-life counterpart with Jia Zhangke’s Ash Is Purest White–one of the American workers has an emotional breakdown. In a scene that shows more compassion than anything Dewang expresses, he’s awakened in realizing the shared connection all humans have.

While much of the documentary is observational in approach, the directors also incorporate one-on-one interviews to get a more expanded, direct perspective on the tribulations of those dealing with the issues at the plant. One man never had a workplace injury in the many years at the GM plant, but got one almost immediately after working at Fuyao. Another reveals the pay cut from $29 an hour at the GM plant down to $12 an hour at Fuyao. Another is initially more inspiring, having been able to move from her sister’s basement to get her own apartment, but when she sides with union organizers, the future gets bleaker. Another strikes up a relationship “like a brother” with one of the Chinese transplants, having him over for Thanksgiving, shooting guns, and riding his Harley, but when that American worker can’t quite keep up with the efficiency that’s expected of him, he’s let go. In perhaps the most substantial arc, one former higher-up at the plant who was furious at talks of unionizing has a change of heart after he sees into the belly of the beast.

But is it truly a beast? The way the directors are able to provide a portrait of empathy on all sides is astounding. We feel for the American workers who are thrust into a difficult, unexpected environment just as much as the Chinese workers, who are forced to be away from their families for years at a time. In a touching display of loneliness, for one Chinese employee, his greatest moment of each day is the cigarette he has after work. American Factory shows how immensely our definition of the American Dream can be altered as we face an increasingly global economy. If manufacturing jobs are going away and we want them to return, what conditions are we prepared to settle with?

With the final scenes recalling Louis Lumière’s landmark film Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory, we’re reminded how vital it is to have filmmakers taking an inside look at the faces and foundations that have built this country. Throughout American Factory as we see the CEO threaten unionization, defend poor working conditions, and smile with glee at the technological unemployment to come, one will constantly wonder how precisely Bognar and Reichert got approval to record and release this footage. This documentary feels like the beginning of a very different America and that we have such an intimate portrait of the change to come is a remarkable achievement.

American Factory premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and opens on August 21.

Follow our festival coverage here.