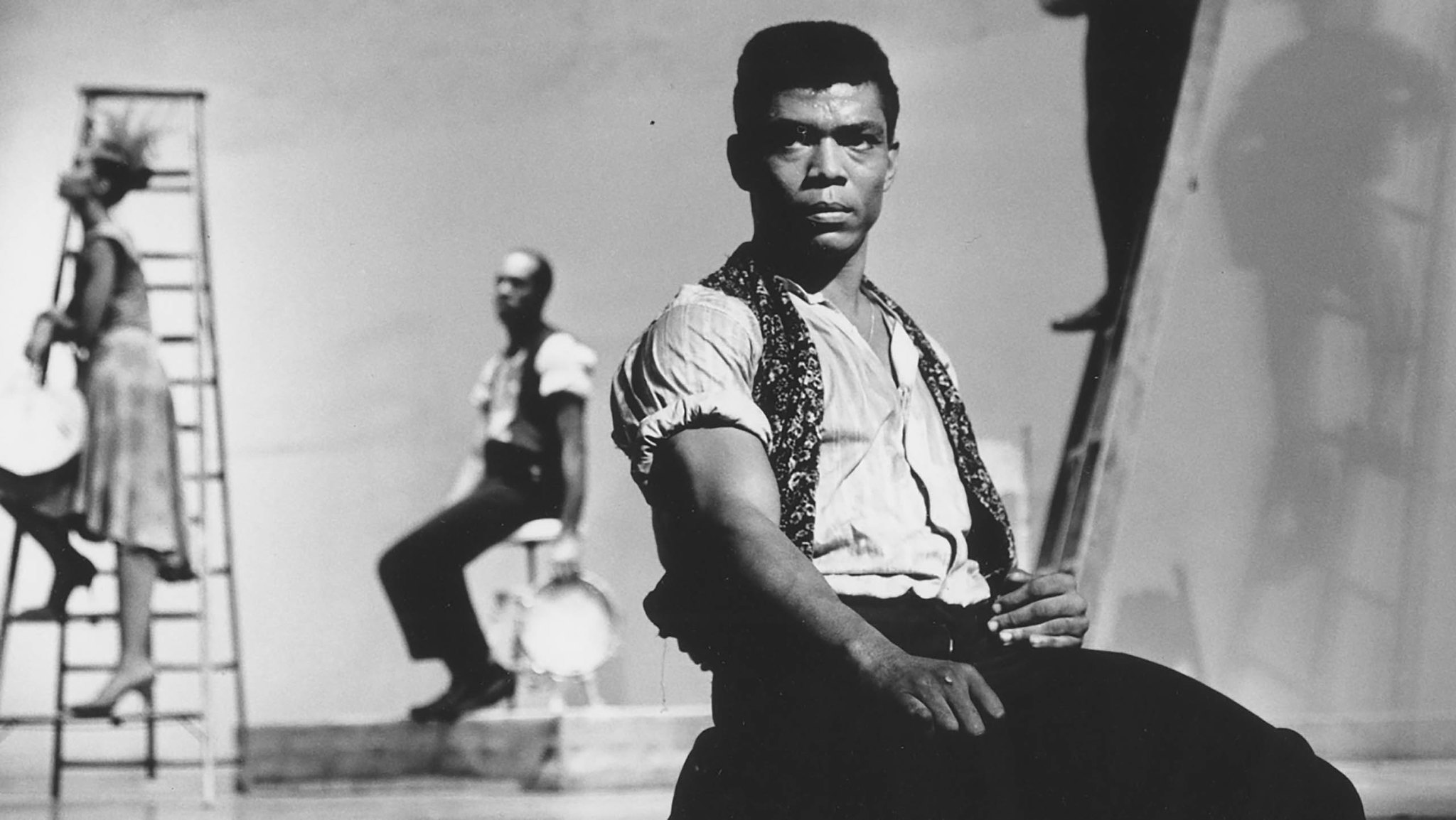

Has any choreographer mattered more to American dance than Alvin Ailey? The documentary Ailey, directed by Jamila Wignot, makes a good case that there has not. Comprised of amazing archival footage, peer interviews, and choreographer Rennie Harris prepping a modern-day performance in honor of the artist, Wignot paints a full picture of a complicated man. Born in the middle of Texas during The Great Depression, old recordings of Ailey recount his picking cotton with his mother (his father was non-existent in his life), then later on seeing Katherine Dunham (and her male backup dancers) perform live. The shock of watching somebody that looked like him produce such wonderful art emboldened him to pursue the work himself.

The structure of the film is fairly standard, utilizing all of its tools to walk through the timeline of the artist’s life; from his childhood, through his eventual arrival in New York City where he would form the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT), developing masterworks such as Blues Suite and Revelations, to his untimely death from HIV/AIDS in 1989. Ailey mainstay Judith Jamison is one of the highlights here, offering up valuable insight into both how the choreographer worked and how he kept most at an arm’s length, even while making his dancers feel loved. Jamison stepped in as co-director of AAADT when Ailey suffered a mental breakdown in 1980. Bill T. Jones, a masterful choreographer in his own right, also speaks to Ailey’s enigmatic nature. The man kept his homosexuality and personal relationships extremely close to the vest.

Harris’ present-day rehearsals serve as a living example of how timeless Ailey’s work is, while some impressive editing by Annukka Lilja connects it all together quite seamlessly. Wignot is smart to keep the dancing front and center throughout. It’s impossible not to be affected by the slow, deliberate emotion of each movement. Ailey made his mark blending spirituals and blues to reflect the African-American experience, providing both representation and collaboration for a thoroughly prejudiced portion of the country. “The fact that Black people get through,” Ailey says, describing his inspiration for Blues Suite. Just as Katherine Dunham and her dancers showed Ailey what was possible, Ailey did the same for so many more.

Ultimately, it’s the archived, audio recordings of Ailey that give the documentary its soul. He describes “looking for a place to be” as a young boy attempting to survive so much hate in the south. “Everybody I had ever dreamed of was here in New York City,” he recalls at another point. There’s a melancholy that drips over Ailey, finally punctuated with hope. As Jamison recalls: “Alvin breathed in [when he died], and never breathed out. That was it. We’re his breath out.” The master’s work survived him, and Ailey shows the art of dance will also survive this pandemic.

Ailey premiered at Sundance Film Festival.