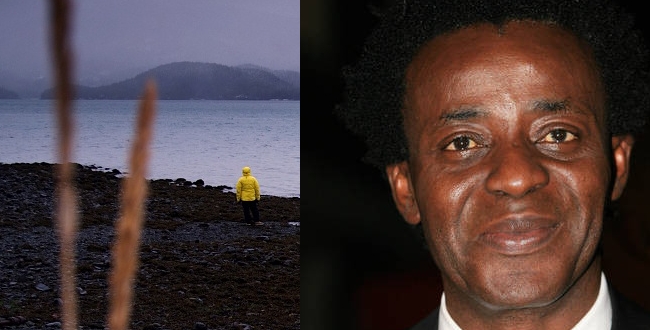

Certainly not a Sundance starlet like Elizabeth Olsen or a storied Sundance vet like Miranda July, British filmmaker John Akomfrah has been making critically-lauded films for two decades – mostly under the public radar. Finally, after years of producing documentaries for companies like the BBC, Akomfrah found himself in a position to make the film he’s wanted to make since the beginning of his career, The Nine Muses: an emotional, abstract look at the intense period of migration to England after World War II up until the 1960s. This rush of diversity spread just as much racial prejudice, forcing those migrants to assimilate to a way of life in England they would never fully fell comfortable being a part of.

The Film Stage spoke with Akomfrah about getting the money, time and material to make this dream project come to life, and how he feels now that it’s open for the whole world to see, showing at two of the biggest film festivals in the world over the last year: Venice and Sundance. As one would expect, the feeling’s both rewarding and anxious. At the tail end of the interview, Akomfrah revealed he couldn’t watch the film in a theater setting, with a full room of eyes. Few know what it’s like watching their dreams become a reality.

TFS: How long have you wanted to make this movie?

John Akomfrah: In some ways I’ve been making it for the last 20 years. Because, you know, visiting the archives, different special archives in England for different projects. It was something that we had been doing anyway, except that, you know, usually what happens is that you’ve got a film to do about a riot or housing so I’m going to those archives specifically for something to illustrate. And I think that’s the difference with this one. For the first time I said ‘you know what, this deserves to be in its own right what it is.’ It’s about trying to build a memorial/monument/altar piece. And I used the religious overtones deliberately. And to that three-generational experiment that took place. And as you do anything you think ‘this is kind of difficult, who’s going to read this?’ But, you know what, you’ve got to do it…there’s no way around it. So, on its own I suppose, specifically, a year and a half. It was originally a single screen – 14-minute single screen- for a gallery. And half way through that I thought, ‘there’s no way we’re going to get everything that I want to get into this.’ So from then on its was like ‘okay, well we’ll do the single-screen piece and when we’re finished we’ll do something longer and when it’s finished we’ll see what it stands as.’ I felt compelled to do it and my sense was what it was for after.

This is your first film at Sundance, after being sought after for some time. Why now?

I don’t know, you know. There’ve been different projects over the years and whether they’ve not come here because Toronto wanted it or it just wasn’t right because I was working on something else. There’s always been a reason over the last 15 years that I couldn’t get here. And there were different projects that the Sundance Institute wanted to support that they couldn’t so there’ve been all kind of possible matchings between me and this festival that have just never happened. I thought we should because it seems to me that the New Frontier slot is what our film… basically I think New Frontier serves to highlight projects with a slightly more ambivalent identity. The question of what they are is itself up for grabs. Are they films? Art pieces? Hymns? What are they? And it seems to be that that’s precisely what this slot is about. So having gone to the equivalent of that in Venice [Film Festival], a slot called New Horizons, which is the first place [The Nine Muses] was shown. When they said they wanted it I said ‘great! If you want the pain you can have it!’ (laughter)

You have a lot of interesting literary references in the film. One of the most interesting is [James] Joyce, who is this Irish writer who grew up in Dublin but then spent most of his life not in Ireland, which fits the idea of identity in your film. How big was that for you?

Big. Very big. Joyce, because of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which ends with him leaving…I mean the thing about the migration to England in particular between the 40s to the mid-60s was that it wasn’t simply people from the Carribean and Africa. They are also half a million that went from Ireland. And I thought that the best way to deal with that migration pattern was via Joyce. Or via the two Irish writers who are much concerned in their writing with this question of how you become something. [Samuel] Beckett and Joyce have talked about this more than just about anybody, so it just seemed right. So, I mean, the other reason why Joyce is so useful is because he serves as a sort of model, in a way, of what we’re trying do here. And in no way am I saying I’m James Joyce by any means. It’s the attempt to find a modern resonance of a classical myth. Because, of course, Ulysses itself is the story of [Homer’s] The Odyssey done…but, of course, everybody in there is a favorite of some kind.

Whether it’s Joyce or Thomas of Milton. They’re all figures that meant a lot to me. But specifically those two (Joyce and Beckett) because, look, nobody talks about this but in the 40s and 50s and 60s you would regularly see signs on houses, would say ‘No Irish, No Blacks.’ And there was a sense of structural humiliation. The people of Irish descent, who were also migrants, felt like [black migrants] felt. And we shared a lot together. We lived in houses together because nobody was renting to either communities and we discovered our own thing together. So the affinity of Irish literature and Irish literal ideals is not simply artistic. It’s deeply felt. Those cultural affinities

This is clearly a very personal project, not unlike those of Godrey Reggio [director of Koyaanisqatsi], who’s trying to get a new project off the ground as we speak. It’s so hard to get money for projects like this these days with companies like the UK Film Council falling apart everyday. You want to make this passion project, how much is too much in terms of obstacles?

Well, they happen occasionally. Reggio’s stuff, Koyaanisqatsi and Powaqqatsi, there was a moment where someone said ‘we’ve got to give this guy some money’ and then [Akomfrah slices the air, signifying a stoppage in funds]. And they appear occasionally, and when they do you should seize them really quickly, because I think what helped in the case of this film was that we had soft money from the [British] Art Coucil and the BBC. The BBC said ‘look, you can have a look at our archives, see what you can make of it, we’ll talk about money afterwards. The Art Council said, ‘we’re funding you as an artist, what do you want?’ So in instances where there are no major equity stakes, no one’s saying ‘oh, is this going to make money?’ things like that are possible. I don’t know whether they will be more possible after. [laughter]

But the thing is when I was talking about Shoah in the beginning [of the Sundance public screening], there’s a moment when [Director Claude] Lanzmann says to this Holocaust survivor ‘you must speak, you must say this.’ And I really felt this ethical imperity to just do this. Now whether we get a chance to do this again or not, I don’t know. Probably not, but the fact is its done and we’ve served the purposes for which it was set to serve, which is to be there as a kind of reference point. I don’t know if I’m going to keep doing films like that, because I’m not sure If I made it. I feel like it kind of made me in a way. Do you know what I mean?

You’re watching material and the material is saying ‘I can say this, I can’t say that. And if you’re going to be faithful to me, you should do that.’ And, in some ways, that’s’ what you get with Godfrey Reggio’s stuff – the sense that everything’s forcing itself from him…I think part of what we share and I think there are a number of other filmmakers who have that. There’s a whole set of filmmakers who think that there’s something there between stories and events. There’s something in the crack between those two. That are worth exploring. When they are explored they make incredible demands of the viewer, and the overwhelming impact is emotional rather than intellectual or visceral rather than cognitive. And everyone who sees them can’t tell you what exactly they’re about but they know they’ve experienced something which is sort of valuable for them. That’s really all I wanted to do, and if it places me in that great company of fantastic filmmakers…look, I don’t come here very often because I don’t get much money very often [laughter]. I suspect that’s something I have in common with [Reggio]. We don’t work that often because we don’t get money to make movies that often.

Did you shoot this film differently because of budgetary constraints? And where did you shoot the film?

I supposed there are three components in the film: there’s the overwhelmingly archival material which is obviously the stuff that came from different institutions. Then there’s two bits of stuff that I shot. One strand, which is the stuff in England, looks slightly grainy of a guy lying in a pipe and all of that. Those were shot 10 years ago for another project and it just felt that because we were doing an art piece my own stuff needed to be in there in some ways. The bulk of the other stuff came from Alaska, and when we first went there it was to make a film for the BBC. Sort of a straight documentary film about the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill in ’89. Well the anniversary was up two years ago so I went there to do that. And I fell in love with the place. So the bulk of this stuff came from Cordova, Anchorage…

So it really is like a compilation or-

Absolutely, it’s very much a compendium of scenes gathered with not necessarily this film in mind. What I wanted to do initially was a piece on T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland.

Really?

Yea. That’s what I shot the material for. And then we were commissioned by the BBC to do this, at some point I thought, as I worked on the two things at the same time, I thought ‘Hang on, it’s the same project really.’

Why didn’t any of Eliot’s poetry make it in [to The Nine Muses]?

Eliot’s poetry didn’t make it in because it seemed too hermetically closed. It’s a very elusive piece which refers to a whole set of other stuff. As we went on I felt that it was something that focused much more on becoming and being and interiority was more important. Whereas Eliot’s is kind of more about the end of a century figure, trying to make sense that they’ve learned. In the end my piece is about somebody who comes to place and really doesn’t know very much…so the lack of process in The Wasteland got in the way. And I removed it to replace it with, initially Beckett because Beckett’s – what you get in Beckett is this idea of someone who’s endlessly checking their own psyche. Those sorts of question seemed more of important for this piece than Eliot.

Well, I loved how you actually skipped Joyce’s Ulysses…

Well, you know, the thing with Ulysses is, if you remember it, those of us who are fortunate to have gone through it, it’s so successfully local. It’s about Dublin in 1905. And the Blooms almost made it. You know, its ceaseless return to Ireland and Irish-ness got in the way. Where as Beckett’s slightly more abstract Everyman in search of himself. It’s a very difficult thing to decide because some of it is what it feels like…It’s a little bit like trying to write a piece of music or something. You got something because you think it’ll work, but actually the note’s wrong. Just not quite right. So, again, having put him in I reluctantly took him out.

Was there ever a moment you thought you might lose grip of what you were making because of how general, how universal, it all was?

All the time, and to be honest I’m not even necessarily sure, to be honest, that I ever controlled it. I think the thing about it is that it’s about something really complicated. It’s about how three or four generations of people of color arrived at a place and tried to make themselves belong to that place. And part of it meant discarding stuff they came with and discovering new ones. Part of it was trying to create the kind of collage of themselves from multiple parts. And there were several moments where I thought ‘well, we should try and drive this more. You know, center it more.’ And at other points I thought ‘you know, slightly more elusive.’ It’s in a way, weirdly, an approximation of the experience. It’s a very fractured, very confusing space. And quite a lot of people spent time in that space and never really felt that they arrived and never really felt they became British. And I think that’s quite a lot of people actually. People from my parents’ generation. They never really, completely became British. They were stuck somewhere between the two worlds, as it were. So it felt more honest, for the project to reflect that, then what you normally get with stories: ‘Oh, you know well, Demi Moore is okay, it’s okay. They were alright.’ [laughter]

That sense of being tied up, that felt dishonest because, in a way, to do that would be, in a way, to say that I know what that narrative is about and I didn’t. I’m looking to myself and saying ‘what does this really mean? Did they ever really become British?’ Well, no I know they didn’t because I knew a lot of them and they sill, to this day, curse the day they left. I mean, you can’t take that completely seriously, because they couldn’t of hated it that much because they stayed. But there is ambiguity and ambivalence at the heart of the migrant experience and I wanted the project to reflect that in a way. For that generation. For mine, it’s a very different story.

– The Nines Muses, by far the best film this critic saw at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival, is currently in talks with distributers about releasing options. And while it will not likely see a theatrical release in the states, it deserves to be sought out and watched and talked about.

What do you think of what Akomfrah has to say about his work of art? Does it intrigue you?