Four decades ago—before he worked with Hayao Miyazaki, before the young artists’ collective he co-founded changed their name from “Daicon Films” to “Studio Gainax,” before Neon Genesis Evangelion shook the medium of anime to its foundations, and before Shin Godzilla affirmed his worldwide recognition as a major figure of contemporary Japanese cinema—a brilliant and unapologetically geeky college student helmed one of the most striking fan films in history. Return of Ultraman, Hideaki Anno’s 1983 directorial debut, is on its surface nothing more or less than a painstakingly exact tribute to the early-70s tokusatsu superhero TV series of the same name: a half-hour “lost episode” indulging the show’s standard dramatic plotline of a Japanese paramilitary group battling monstrous kaiju invaders, with one of their members concealing and frequently angsting over his secret identity as a part-man, part-alien super-savior. (Ultraman’s creator, Eiji Tsubaraya, was a special-effects icon who produced wartime propaganda for the Imperial Japanese Army and later converted to Catholicism.) Despite its amateur production and shoestring resources, the film stealthily advertised the birth of a preternaturally gifted filmmaker. Its lovingly crafted sets, props, and costumes rivaled those of its pulpy source material, and its complex shots, propulsive editing, and powerful expressionist compositions in many cases exceeded it. Anno’s deeper visual vocabulary adds a philosophical spin to the proceedings: pristine military hardware and grimy biological monstrosities are depicted in parallel as dueling titans, and feverish attention paid to the procedural specifics and human drama of its armed defense forces (including an icy, imposing, paternalistic commander) reframe Ultraman’s quasi-religious identity crisis as a metaphor for social institutions themselves, humanity’s mechanical and biological aspects in-tandem producing an unstable entity that could save or doom them. In a postmodern twist, the film’s climax sees the hero transform not into his familiar masked visage, but rather Anno himself in Ultraman cosplay wrestling a rubbery tentacled monster. To fans of Anno’s subsequent work I ask: is any of this sounding familiar?

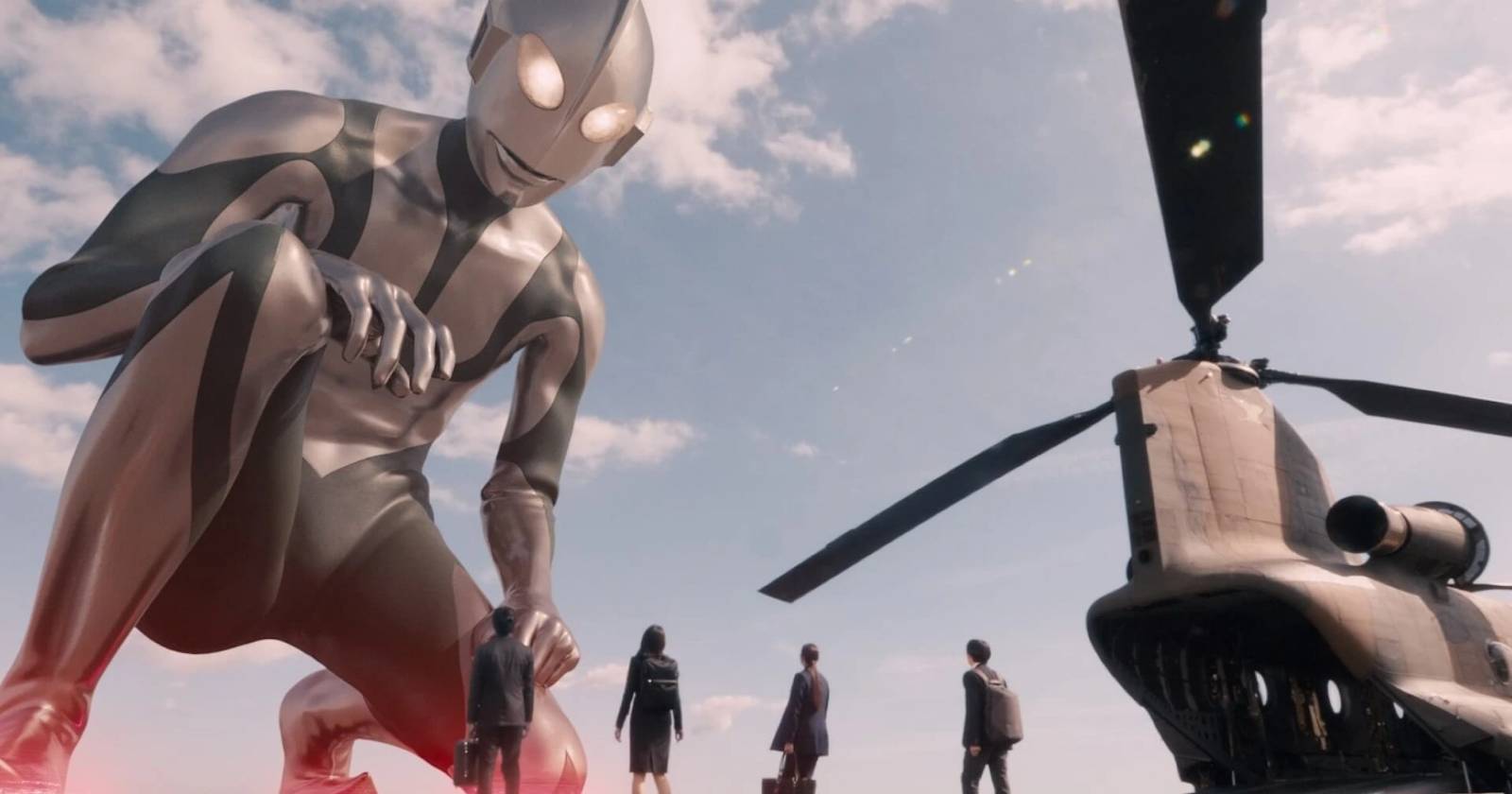

At the other end of a storied career, Shin Ultraman arrives draped in Anno’s name: as producer, screenwriter, co-editor, co-cinematographer, and even reprising his role as actor inside the rubber super-suit (this time with mask on). In the director’s chair, however, is Shinji Higuchi, Anno’s longtime friend and collaborator, whose best-known solo work is the live-action adaptation of megahit manga Attack on Titan. The film, a spiritual followup to 2016’s Shin Godzilla and the second in a planned trilogy of “Shin” tokusatsu franchise reboot films—the Anno-helmed Shin Kamen Rider is coming later this year—attempts, as with Godzilla, to be at once a gritty modern reboot, retro celebration of, and academic metatext on its source material. Anno’s confoundingly dense script, drawing from the classic TV series as well as his own revisionist spin on the material, feels like an entire trilogy of superhero films crammed into less than two hours. It’s a fuming, many-faceted contraption that blazes at breakneck pace through plotlines, gags, setpieces, capital-L Lore, and heavy philosophical musings that re-resituate its hero’s dual earthling / extraterrestrial identity as metaphor for the tension of individual and structural social actors, as well as Japanese national identity and the gnostic theological concerns familiar from Anno’s prior work. Yes, it’s a lot. Some whiplash is involved.

The film’s hyper-empirical style and procedural focus (cuts are many, expository subtitles abound, and get ready for more than a few boardroom debate scenes) feel like immediate successors to Shin Godzilla, and indeed the opening minutes dive right into a familiar conflict between invading alien titans and the Japanese government agencies tasked with repelling them. Shin Godzilla’s postmodern take on kaiju used its own orgy of empiricism—bureaucratic titles, intelligence reports, security footage, social-media posts—to establish a simple, film-length duel between mankind (specifically the nation of Japan) as a complex, messy collective entity and Godzilla as a singular force of nature.

Shin Ultraman quickly diverges from that focus, following the individualist logic of superhero narratives into something strangely resembling an office comedy. Villains come and go (it’s not too big a spoiler to say the film has at least four distinct baddies) but the main focus is the conflicting personalities of Ultraman (alter ego Shinji Kaminaga, portrayed by Takumi Saitoh) and his small team of kaiju-busting coworkers, especially go-getter career woman Hiroko Asami (Masami Nagasawa). Not only must Ultraman negotiate his secret identity with his coworkers, but also wrestle with duty in the face of conflicting incentives. Despite his abilities he is simultaneously empowered and constrained by his position within a legalistic power structure, utilizing the resources of the state to locate and contain his increasingly sophisticated opponents while burdened by the limits of procedure and the rulings of institutionally self-interested diplomats and figureheads who would welcome or even negotiate with these crafty foreign superpowers rather than expel them. (Hmm…) To protect and serve, in the end, he must act individually against the structure (the Japanese government) to subsume his identity and very life to the greater structure (Japan).

Give or take the intense philosophizing laid on throughout, it’s not a totally unfamiliar dilemma for “serious” superhero narratives on this side of the Pacific, and its thesis of maverick military self-sacrifice as dialectical synthesis of individual and collective wills recalls to this critic that Tony Scott’s Top Gun is a film more intellectually savvy in its gung-ho militaristic nationalism than it often gets credit for. (Anno, whose first anime series was directly named after and parodies that film, is a noted fan.)

When Shin Ultraman is not being “serious,” of course, it is deliriously silly. The film often goes for comic relief, and in its overstuffed mass of ingredients and breakneck pacing it tends to push characterization to the side, reducing its heroes when they aren’t exposition or philosophy mouthpieces to a series of goofy quirks—Kaminaga’s big on Star Trek collectibles; Asami slaps her own ass, and eventually those of others, as a form of motivation—a drastic departure from the intense inward focus of Anno’s mid-period work. What Shinji Higuchi most obviously and successfully brings to the table is a vision of CGI not as a vehicle for photorealistic illusion, but for the high-fidelity evocation of men in rubber suits. Alien monsters have a delightfully tactile, toyetic quality to their tentacles and carapaces and oblong glowy bits, and in Ultraman’s flashy stunts you can practically see the suspension wires. It’s a refreshing departure from the impersonal, immaterial grit of Hollywood’s standard approach to CG spectacle, and one that recalls in the best way the exaggerated textures and tactile cartoon physics of Ang Lee’s eternally underappreciated Hulk (another film in which a star director personally donned the mocap suit to bring its hero’s super-movements to life). In these images Higuchi gets to let his own talents sing, and it serves him better than in the human-scale scenes that often feel like merely competent imitations of Anno: strange and angular Anno-esque compositions abound, but few possess the density or expressive purpose evident in Anno’s own work.

Alan Moore once opined, decades after the fact, that perhaps in writing Watchmen, the original postmodern metatext on the mythology of the superhero (well, a few months after The Dark Knight Returns) he had overextended himself trying to impose Great Meaning onto an adolescent pulp genre that couldn’t bear the weight. Half an hour or so into Shin Ultraman, a throwaway gag of Kaminaga / Ultraman reading some Claude Levi-Strauss on the job drives home how this film, even more than the rest of Anno’s corpus, buckles under the stress of its own bifurcated identity. This is a film that will attempt to tickle its audience with an Attack of the 50 Foot Woman parody in one scene, bombard them with science fantasy jargon the next, and sit down for a deadly serious intellectual discourse immediately after that—all in the interest of servicing its venerated entertainment property. American critics, no doubt struck by its novelty, are already hailing the film as an artful departure from the doldrums of our own country’s superhero output, but in its home country the blitz of nu-Anno franchise merchandising is well underway and set to continue for the foreseeable future.

It’s hard to believe, from either his position or politics, that Anno was at one time anything resembling a radical within the Japanese film industry, specifically one who preached the emptiness of pop-culture escapism and the necessity of leaving childish fantasies in childhood. I can’t imagine too many children will manage to follow Shin Ultraman’s decades-old pop culture throwbacks, relentless volume of plot or reams of dialogue trying to vindicate the property as a vehicle for philosophical inquiry, though they will surely appreciate the kaiju fights. What I can’t help but miss in all this is the poetic free spirit and deep human interest that once defined most things associated with Hideaki Anno—his concerns, it seems, have shifted from individual to structural, and perhaps people just aren’t so compelling to him anymore. Higuchi’s evidently having a great deal of fun, however, and surely has more of those rubbery monsters up his sleeve. He’s doing fine.

Shin Ultraman screened in a limited theatrical engagement and will be available on home video later this year.