Writing about the films of Robert Bresson usually begins by informing reader that his films must be discussed through a trance of hushed tones and quiet veneration. There is no room for rushed judgement or quick-witted observations; Bresson makes Serious Art, as opposed to Hollywood directors who do not. There are the key phrases to use — what B. Kite calls part of The Critical Dictionary of Received Ideas (“ascetic, austere, severe, demanding, slow, transcendent, Jansenist, minimalist”) — though how these relate to what’s on screen is often left unexplored. Most importantly, one must fully concede themselves to the films, giving into the Power of the Holy Spirit instead of analyzing or critically exploring them, and especially not simply enjoying them.

So in revisiting Pickpocket, now out through Criterion Blu-ray, I found it more interesting as a genre picture than reverently accepting it in the category of Transcendental Style In Film. There is much to consider when examining Bresson’s form, but I find it has less in common with the contemporary art house that has adapted his influential techniques (often just “model”acting) and more similarities with the Pre-Code films at Warner Brothers. This is not just because Pickpocket is, in some ways, a gangster film, but because the way Bresson tells his stories visually — through glances, visual details, and, most essentially, editing — is less an ascetic tendency than one of economy, the same kind we recognize in Mervyn LeRoy or Allan Dwan.

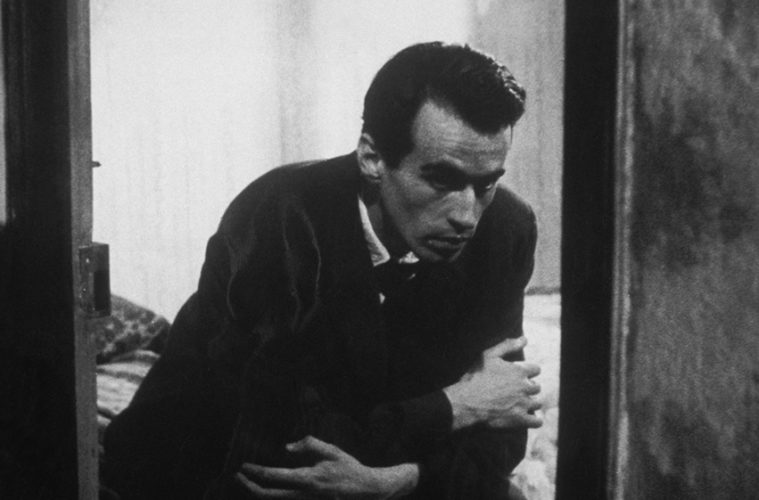

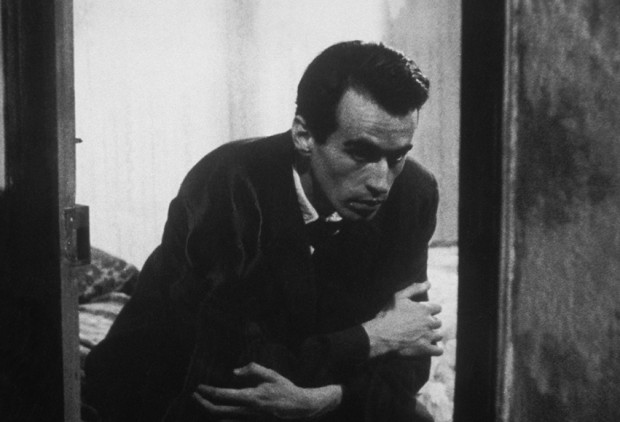

The opening scene of Pickpocket illustrates Bresson’s economic style, as Michel — a wannabe Dostoevskian supermensch making his way through every coat in Paris — stalks an old woman at a racetrack. Bresson simply cuts between two shots: Michel joining the spectators in looking at the racetrack (the horses are never seen — sound design does the trick) and Michel’s hand slowly reaching into the purse. Bresson communicates the action through what David Bordwell calls constructive editing (illustrated in a later scene here): the two spatial areas are connected through lead Martin LaSalle brief glances down, thus matching his hands to his body and the entire action of pickpocketing. Two shots cutting back and forth are all Bresson needs, and dutifully illustrate something many slow-cinema artists have abandoned.

It’s this kind of marvelous precision that is often lost in discussions of Bresson. Pickpocket is a film made from material gestures, not that far from what is experienced during a Buster Keaton stunt — using artificial means and making action feel physical, and if you can do so with minimum effort, the better. Keaton may have relied widescreen and unbroken takes for his stunts, there is a line in James Agee’s iconic piece that jumps out in terms of thinking about Bresson: “In a way his pictures are like a transcendent juggling act in which it seems that the whole universe is in exquisite flying motion and the one point of repose is the juggler’s effortless, uninterested face.” For as much as Bresson turns LaSalle into a stone-faced model, the rest of his universe is chaos: busy streets crammed with people (Michel dashes onto a last-minute trolley at one point), amusement rides spinning in the background, and the police captain who can’t take that smirk off his face. In the same way Keaton wants to control the universe, so does Michel (and quite literally, when it comes to his philosophy).

There is, too, a narrative impulse to Pickpocket that certainly seems more economic than contemporary art-house cinema’s three-hour-plus running times — the journey is over in 75 minutes flat. For all of Bresson’s cinematic philosophy (and Bresson was one of the greatest proprietors of ruminating about cinema), Pickpocket never shies from purely “cinematic” pleasures in conveying its narrative. The film’s montages — reminiscent of those in LeRoy’s I Am A Fugitive From a Chain Gang or Raoul Walsh’s The Roaring Twenties — effectively pass time through a series of dissolves, such as the training montage of Michel repeating the same series of hand gestures more quickly and effectively with each passing shot. Some of Bresson’s sequences even use one of the simplest narrative tricks in the book — the withholding and revealing of information. There’s a moment where Michel abandons his friends to chase down a watch that’s still dangling from a person’s wrist; Bresson then cuts to Michel arriving home, his clothes tattered and a cut on his face. In voiceover, he notes that he fell, though the circumstances of his fall are unknown. Jacques arrives to question him about where he went off to, and the two duel their way through their dialogue, Michel avoiding the truth at any cost. It is only after Jacques gives up and leaves when Michel finally reveals that yes, he did get that watch after all, which Bresson completes with a cue of the orchestral score to join the narrative surprise. This is the kind of narrative event we come to expect in Hitchcock, but one that has been erased from our thoughts on Bresson.

What, then, is the difference between being ascetic and being economic? Is it simply that one condones “notes of serious inquiry” while the other one represents “Hollywood”? When watching Pickpocket, it is easy to ascribe many things onto the film — the possible Freudian and homosexual tendencies, the heavy Catholic guilt, and Bresson’s critiques of French society (more prominent in The Devil, Probably and L’Argent). Lost in these readings is a simple description of what happens in the film. There’s the moment where Michel lies to the police captain, who catches that lie by simply tracing the dust off his book jacket. There’s a shot where Bresson’s camera glides down with an undercover cop’s hand at the racetrack, ending with a perfectly timed click sound as money drops and other viewers begin to move. And, of course, the great ballet of three pickpocketers working their way through a train station. Why not place it alongside the finale of An American in Paris or the tea-house shootout in Hard Boiled? They all come from the same craft of moving characters around from A to B in rhythmic action, connecting every physical detail and making sure they have a necessary consequence in the following edit (Johnnie To restaged it, after all, for the finale of Sparrow).

Bresson is many things — if he was one thing, he probably wouldn’t be considered a great filmmaker — and it’s easy to trace his films as unflinching portraits of solitude. A healthy, worthwhile debate over the final moments of Pickpocket — as Michel and Jeanne’s eyes meet, the recognition of personhood that has become a recurring moment repeated in almost every Dardenne brothers film — will probably require a more elevated approach to understanding the director’s goals. Too often, however, the focus on Bresson concerns what he is not doing instead of what he is doing: creating action, seeing how things actually move in the world and focusing intently and exclusively on those gestures. Kent Jones quotes Chandler in his own piece on Bresson: “My theory was that the readers just thought they cared about nothing but the action. The things they remembered, that haunted them, [were] not, for example, that a man got killed but that in the moment of his death he was trying to pick a paper clip up off the polished surface of a desk and it kept slipping away from him.”Because of its genre, Pickpocket is certainly the closest Bresson comes to the hard-boiled writer, but it’s through his cinematic technique — the way things are physically felt by the camera in his films — that we can then begin to contemplate what may lie beyond it.

Pickpocket is now available on Criterion Blu-ray.