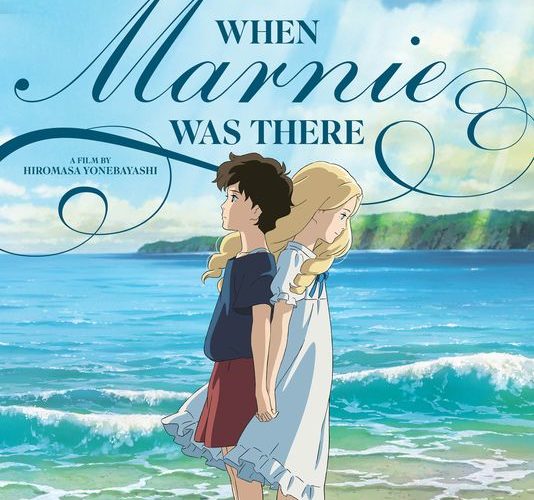

If Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s When Marnie Was There does turn out to be the last Studio Ghibli theatrical film, then the animation powerhouse will be going out on a strong, expectedly poignant grace note. Sure, the recent Hayao Miyazaki wonder, The Wind Rises, or Isao Takahata’s lovely, poetic Tale of the Princess Kaguya might have proved more significant swan songs, but this dreamy, gentle extrapolation of author Joan G. Robinson’s decidedly English ghost story reinforces some of the smaller, subtler delights Ghibli specialized in over its long, glorious career. The story itself alternates between shimmering slightness and downright ephemeral haziness, but the gorgeous, melancholic animation and quiet, compassionate direction of Yonebayashi (2010’s somewhat underrated Arrietty) carry this portrait of a young girl fearful of growing up, and the mysterious playmate she befriends at a moldering mansion in the marsh.

Although the presiding feeling of that creepy old house and the bucolic countryside it inhabits is entrenched in European gothic sensibility, the movie itself retains the overall whimsy and naturalistic magic of its Ghibli precursors, particularly the understated Whispers of the Heart. Both movies use the animated form to externally embody the sensitive and apprehensive headspace of uncertain and jittery pre-teen antagonists, setting aside the exaggerated and often surreal fantasias that usually make up the studio’s bread and butter. There’s a freedom of expression that doesn’t exist in many Western forms of the medium, and it’s an almost refreshing shock that the opening sequence features the protagonist experiencing a bout of ‘asthma’ that the adult characters discuss and treat as if it were a panic attack.

Right from the beginning, Anna (voiced in this English dub by Hailee Steinfeld) feels distant and cut-off from her classmates and the people who surround her. When the attack happens, she’s sent off to the countryside to live with a hospitable aunt and uncle she’s barely met before. The dialogue of the adults here give suggestions that there’s more going on with Anna than they quite know what to do with (a change of pace and scenery are hoped to help her mood) while Anna’s own thoughts are less subtle about her emotional state, which seemingly borders on depression. Once Anna arrives in the windswept fishing village of Kushiro and discovers Marnie (Kiernan Shipka) and the Marsh House, the movie finally comes into its own.

The animators take great care evoking a world that sits halfway between idyllic mundane realities and mysterious romantic notions. Anna, who spends more time sketching in notepads than talking to peers, sees her world with the sensitive but sometimes fretful gaze of an artist, and just as Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises adjusted its imagery to reflect its airplane designer’s worldview, so does Marnie configure its spaces to imitate Anna’s imaginative stores. Most Ghibli films are undeniable on the terms of their visuals and artistry and Marnie is no exception; in fact, here the visuals sometimes counter for substance, the way Yonebashi lets us drink them in accounts for the patient, mysterious mood conjured once the character of Marnie enters the story.

Blonde-tressed and living a strange, disconnected life with a peculiar and remote family, Marnie attracts the friendship of Anna, who hasn’t previously held much interest in personal relationships of any kind. Marnie lives in a world that seemingly exists out of time, and to get to her old mansion, one must cross the land when the tides are low. When the girls are together, they instantly connect and orbit around each other indulging in accounts of one another’s lives. Their experience and knowledge are limited, but together they find kinship and solace, so much so that the friendship begins to shape and change Anna’s own personality. In a different, darker movie that wanted to exploit the supernatural angles that pop up, we might learn that Marnie is a menacing and corruptive influence, but this film stays within the boundaries of its characters, and relishes in the little details that tend to accumulate around a brightly-burning young friendship.

When the film focuses in on Marnie and Anna and the worlds they inhabit, it practically soars and gathers us up in its warm but haunting embrace. As the mystery itself finally needs unveiling, and Anna works to uncover the truth about her friend, the movie becomes somewhat pedestrian and borders on unchecked sentimentality. For so much of its running time, Marnie weaves in and out of a youthful perspective of an adult world’s fears and dangers. Towards the end–despite an effective coda resolving Marnie’s presence–Yonebayashi winds down his gears, and as the film should be putting the finishing touches on its poetry it chooses to coast on some of the easy emotional beats.

It’s easy to see the flaws in When Marnie Was There, but its strengths again speak to the power that Studio Ghibli has brought to family entertainment over the years. Here is a film that depends on the sensitive better natures of our character to earn its dramatic depth, and it appeals to kids young and old who would rather be enchanted by heartfelt characters than grand spectacle. In this way the audience can relate to Anna, whose disenchantment is enlivened–of only for a little while–by an adventurous spirit calling to us from the distance.

When Marnie Was There is now playing in limited release.