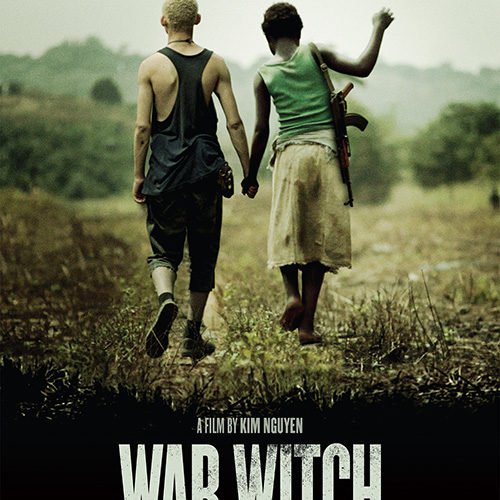

It was a news headline focused on child soldiers in Africa embroiled in war and transformed into deity-like figures that inspired writer/director Kim Nguyen to create his Oscar nominated film Rebelle [War Witch]. Learning about prepubescent twins Johnny and Luther Htoo led to more research on the phenomenon and the idea to craft a tale speaking towards the resilience necessary for so many unwitting victims of civil unrest to survive. Atrocities are committed to them, by them, and eventually because of them once manipulation and naivety turn innocence into a distant memory. For his heroine Komona (Rachel Mwanza), twelve years on this earth could never have prepared her for the hell she’d soon be lost inside. Superstition and faith are twisted until murder is made justifiable and war an inevitable, perpetual way of life.

Her journey is a harrowing one captured as though memories told to her child—events that led her to giving birth within our highly-destructive world. She’s introduced to us enjoying life with her family as a young girl finding her way until the Rebels row ashore. Armed with AK-47s and bad attitudes, these soldiers are merely kids following orders from their leader Great Tiger (Mizinga Mwinga) to kill, enlist, and scavenge. To them the younger their prisoner the better—youth an attribute easily malleable to their purposes. Given a choice to shoot her parents or watch as a rebel commander (Alain Lino Mic Eli Bastien) painfully murders them with a machete before turning the blade on her, Komona does the unthinkable. War takes her and this initiation proves understandably impossible to shake.

Beaten and starved during training, she and the other kids from her village assimilate by pantomime first and live ammunition second. There is a certain dark magic involved with “wizards” and “seers” appearing to be a huge part of the fight by guiding the Rebels forward and protecting them from harm. Great Tiger possesses a mystical black rock called the Coltan he will kill to protect, a young boy named Magician (Serge Kanyinda) keeps an African amulet called a grigri close to his chest, and any object passed down or given to another is done so with very specific ritualization. The Gods are close to the fight as overseers give credence to the bloodshed and all examples of the unexplainable possessing positive results become labeled witchcraft securing victory.

Shot in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, we’re transported into the feral carnage of this civil war as children with guns wage battle against government soldiers across the terrain. Narrated by Komona’s voiceover, these glimpses are short bursts of recollection either of pain, fear, or the few joyous moments she somehow finds herself sharing. From the brutality of her superiors molding her into a killing machine to the hallucinogenic properties of “magic milk” from the trees, each moment is depicted through a very personal filter. The tears pouring down her face as she slays her parents are real; the screams uttered in response to the thwack of a stick as punishment piercing; and the powdered skin, white eyed ghosts cropping up to warn her chilling to the bone.

These visions become her salvation as one’s order of “Run!” forces her to dart back through the words while her brethren fall prey to the enemy. Whether manifestations of guilt mixed with the drug-like milk or true witchcraft flowing through her blood, this one incident vaults her from enslaved warrior to Great Tiger’s personal possession. Just one more myth bred out of fear for the unknown, her status is anything but permanent as her general has killed his previous three. The appointment is but a superstitious necessity to make her into a lucky charm, something all are too young to understand besides Magician. Only he sees the truth of what has ruled his life for too long. Only his love for Komona can force him to strive for something more.

Like all great tragedies, however, escape is never as easy as it seems. For these young lovers happiness is but a fleeting glimpse into what might have been if they were born anyone else besides their Sub-Saharan homes. They live amongst Magician’s kin under the roof of his uncle the butcher (Ralph Prosper) as an old test of finding a white rooster to earn a lady’s hand in marriage brings a much needed streak of frivolity and humor to cut through the depression ruling this three-year period of Komona’s life. The war finds them to cut their joy short and reintroduce the horrors raging around them of which they can never be saved. This lifestyle has altered them on a primal level and neither may ever be free again.

War Witch depicts the hope humanity holds onto to rise from the ashes of the scorched earth from which we come. Life throws challenges that will force our hand and try to destroy us if we comply. What some easily exploit as gift may in fact be the haunting of our conscience beckoning us to right wrongs and not succumb to the tragedy surrounding our every move. The actors Nguyen found to play these brainwashed soldiers are menacing and terrible in their juxtaposition of age and action while the warmth, fortitude, and courage of his leads lift them above cliché. Mwanza deserves each auspicious award she’s received, shifting from helpless to fearsome to calm as her character’s experiences overwhelm. It’s a star-making turn inside a dangerous world—one we’d rather not believe exists—laid bare.

War Witch is now in limited release.