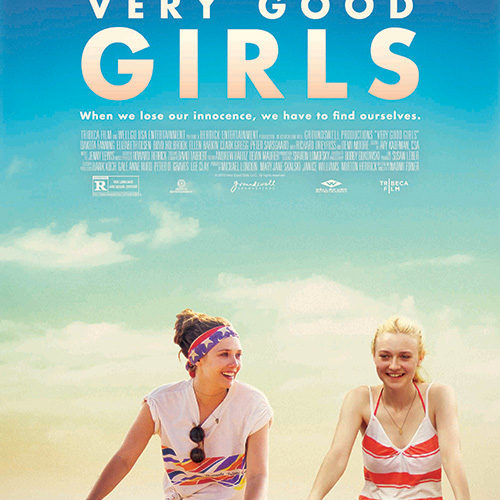

Writer/director Naomi Foner wants to tell us about the messiness of life through two eighteen-year old girls during their final summer before college. You’d assume they’d be the ideal candidates to do so too once they simultaneously make a pact to lose their virginity and meet the guy of both their dreams, but Very Good Girls refuses to let the ramifications of that stand on their own. Instead Foner adds parental infidelity, untimely death, sexual harassment, and a ton of lustful jealousy to muddy the waters and make the last few weeks these BFFs have an emotional nightmare of epically teenaged proportions. As a result the inevitable confrontation between Lilly (Dakota Fanning) and Gerry (Elizabeth Olsen) comes too late and their attempt at reconciliation too soon to give their pain adequate room to feel poignant or real.

When you read the synopsis and discover there will be a love triangle between the girls and burgeoning photographer David (Boyd Holbrook) that will “test their friendship for the first time,” you prepare for the emotional fallout of what this situation entails. Foner even provides some tense moments thanks to Fanning’s authentic internal struggle and Olsen’s bubbly optimism as the former sleeps with him and the unaware latter innocently queries whether she should call him for a date. The truth begs to be told: maybe Lilly’s conscience will get the better of her in the face of tragedy or perhaps David will let something slip unsure of how much Gerry knows. Only when that happens can we finally see its destruction, how they’ll attempt to reconcile, and recall similar situations from our own formidable years in the process.

Foner appears to want to play with our expectations, though, by continuously throwing wrenches into the mix to either postpone Lilly’s confession or increase her guilt. She infuses periphery examples of trust issues between loved ones courtesy of Lilly’s Dad (Clark Gregg) being caught in an affair and thrown out of the house by Mom (Ellen Barkin) and the unorthodox love from Gerry’s more hippie, free flowing parents and possible swingers Danny (Richard Dreyfus) and Kate (Demi Moore). This adult turmoil adds to the heightened emotional strife the girls face on top of their yearning to “become women” before college, giving them excuses to rebel with the bad boy or seek comfort from a caring shoulder respectively. As a result, David becomes exactly what they each need separately rather than a three-dimensional human being himself.

I guess that’s okay since no one really gets fleshed out beyond what’s needed to service the plot. Even Lilly and Gerry are introduced with little detail other than the fact that one is leaving for college and the other staying. It ends up being the myriad hardships pouring down during their contrived summer of lesson building situations that finally gives them a chance to have personalities. And when they do—especially when Lilly reveals the selfishness love brings out of her—proves to the best part. That doesn’t mean they can skate by without consequences, though, and the way Foner ends the film seems like she’s okay with them doing exactly that. Maybe I simply don’t understand the impenetrably powerful dynamic of teenage girl friendship, but I needed more hostility all around.

In all honesty, I had no love for Lilly at all (credit Fanning with her accurate portrayal of angst and insatiable lust). She’s the manipulator throughout the entire film: ignoring the pain her father’s infidelity brings her mother in lieu of what it does to her and her sisters, telling Gerry she has amazing parents and to stop being embarrassed by them, and stringing David along until his presence in her life becomes more trouble than joy. I hated her because I couldn’t help wonder if I’d act the same way in her situation. With college looming as a huge personal challenge, all these other adult and infinitely more important situations present themselves. Her escape is a boy, a boy who pulls her away from her confidant. And like a confused teen should, she loses her way.

In contrast, we pity Gerry for getting the short straw and being completely in the dark as to how the one person she leans on is rigging the game. Olsen’s infectious smile, ability to give Lilly the benefit of the doubt no matter what dark cloud looms overhead, and almost unblemished genuineness can’t help but endear her to all watching. Foner fleshed her stars out wonderfully in this way—our compassion for one increasing our anger at the other. We pick sides, desire vindication for Gerry, and possibly even revel in Lilly’s self-induced comeuppance at the hands of David and her smarmy boss (Peter Sarsgaard). We allow ourselves to become complicit in Lilly’s suffering, ignoring her remorse and forgetting how it also hurts Gerry. It took too long to come to a head, but the initial payoff works.

Sadly, beyond that specific interaction—the one the movie revolves around—there’s too many other things happening. It all wants to infer upon the girls’ feelings towards each other, but their resulting attitudes change too quickly and expose how blatantly transparent those wrinkles were to “teaching” them life’s pain. Everyone is used to place Lilly and Gerry on their collision course, yet the impact isn’t powerful enough to warrant suspension of disbelief. We should forget the contrivances because we’re wrapped up in how the girls act during the aftermath, but we aren’t given that privilege. We receive maybe ten minutes before Foner thrusts them together once more to see what happens. After the weighty drama surplus we’re left with two teens much less affected than I believed necessary, making me wonder what the point of it all was.

Very Good Girls hits limited theaters today.