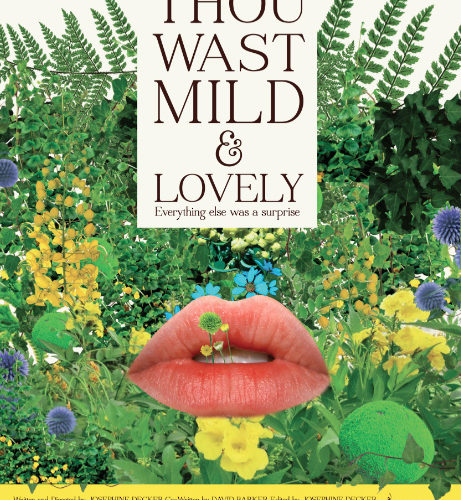

She is not kidding when she says: “To those who feel that their cruelty is too cruel, their sadness too sad, I dedicate this film: an embrace.” Writer/director Josephine Decker means every single word because she herself has laid bare her own cruelty and sadness with Thou Wast Mild and Lovely. Her characters are flawed, dangerous, and inviting—animals working the farm yet animals just the same. They each desire, take, and enjoy, suffering the psychological consequences after the fact, unregretful for what they’ve done. They speak about the strangeness of each other, intellectualize they own positions of superiority, and then willfully allow themselves to be eaten just the same. There is most certainly pleasure in their pain. They ask for it and it devours.

It’s no surprise to hear how difficult it was for Decker to mold what she’d written and filmed into the vision she hoped. Deeply violent and erotically wicked, she has forced her characters against a wall and watched to see how they’d react. Similar to her debut Butter on the Latch, she and cinematographer Ashley Connor shot scenes with a lumbering focus floating and spinning as actors come in and out of frame. Decker and co-writer David Barker also found a delicate balance in the darkness with second-long glimpses at bloody faces, titillating forms, and the overpowering sounds of panting and screams. Their story is as much a tonal poem worming its way under your skin as it is quiet Akin (Joe Swanberg) lost in a sexual tease of escape.

On the surface it’s simply a summer job for extra money on a farm owned by Jeremiah (Robert Longstreet) and his daughter Sarah (Sophie Traub). Akin is just the latest in a long line of helpers traveling to their land because he cannot remain home. He has a wife and a child mired in a tragedy we don’t yet know despite it weighing on him and his actions meant to leave that life behind for a little while at least. That’s why he removes his wedding ring, why he lingers on Sarah seen through open doors and windows in her underwear or less, and why he struggles to remain private and unattached whenever Jeremiah’s leering smile turns his way with a prying question or passive aggressive insult meant to earn a rise.

Akin plays the stranger angle too well, though, and ultimately gets caught inside a disturbing sexual triangle that spills over into a tense air of uncertainty. He cannot help himself from falling over the line separating his isolation from his urges, wanting Sarah close as long as who he is stays a mystery. It may work for a few days and weeks, but eventually these farmers’ eccentricities reveal more than the curiosity of people cut off from the larger world we know. Their smiles grow more mischievous and their poking and prodding more surgical until Jeremiah finds his opening to throw in the wrench he knows can only lead to excitement whether the resulting collision is mutual or not. Because as soon as Akin’s wife Drew (Kristin Slaysman) arrives, all bets are off.

Decker is a master at subverting what she shows us by doing so twice and with vastly different meanings. What is in Jeremiah’s barn, for instance? Is it an injured beast or a man held in captivity? Do her metaphors of cows and horses dealing with the precision of carnal pleasures reach out into the visual world as well with man and animal reverberating form in the darkness? Fantasies of pain make way towards ecstasy, ecstasy of pleasure resulting in detached embarrassment. Both Akin and Sarah find themselves in the throes of lustful thoughts, wanting each other as well as the woman positioned to keep them apart. And when the three come together in a gorgeously shot sequence of deflection, blindness, and unrestrained hunger you know it can only end in suffering.

I don’t know what nightmarish realities Decker has experienced or thought up to reveal her inner ugliness here, but the details are inconsequential when you’re willing to look within at your own pitch black grotesquery hidden so well. The things she puts onscreen make you fear what’s to come and yet you find yourself craving it as much as the characters do. The level of appetite differs depending on your personal grade of depravity, but the blood spills without your flinching. Everyone’s fantasizing how far they might be able to go—Akin wanting to forget his pain, Sarah yearning to quench her thirst, and Jeremiah looking to take everything by force. And all the while the film’s title wears its tense as a warning because not even you the viewer can be called mild or lovely by its end.

Thou Wast Mild & Lovely is now playing at the IFP Media Center in New York City.