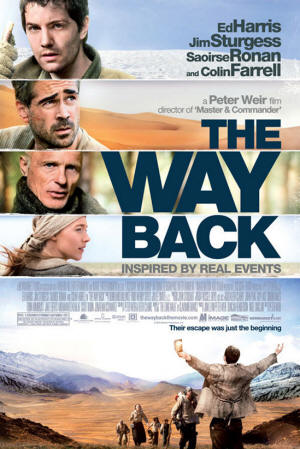

Above all else, Peter Weir‘s new film, The Way Back, is a challenge. Telling the ‘based on a true story’ tale of a group of WWII POW’s escape from a Siberian gulag, Weir isn’t so much interested in the drama of the journey as he is in the journey itself. Where other prison break films imply large scores and grand speeches, this has neither. And though there be plenty of wide shots exploring the vast landscape the group traverses (they travelled 4,000 miles to India for refuge), much of the film is shot right in its actors’ faces, exploring every scar and pore available.

Only the least amount of time is spent in the gulag itself, introducing those who will comprise the journeymen and not much else. This includes Jim Sturgess as the strong-hearted Janusz, Ed Harris as the tough-nut American who goes by only Mr. Smith and Colin Farrell as the ruthless Russian criminal Valka. Soon they escape thanks to a faulty generator and what appears to be lackluster security. All of it happens so quick and without much verve. The music only begins to rise once they’re on the run.

Farrell steals scenes as the upfront villain of the bunch while Sturgess, who’s meant to be the anchor of the picture, has yet to grow into any kind of leading man, despite the promise of his performance in Fifty Dead Man Walking. Oddly, most of his acting in this film is reactionary, though his backstory is the only one we see. Fittingly then, Ed Harris’ character, who we know perhaps the least about, is so internal and, in turn, so intriguing to watch that he becomes the easiest to sympathize with. At moments it does feel as though Mr. Harris is man working among boys. The topography of his worn face is enough to keep even the most attention-craved viewer interested.

The script, written by Keith R. Clarke and Weir, never quite comes to life, vastly overshadowed by cinematographer Russell Boyd‘s keen eye. Weir and Boyd work with lenses and focus in traditional ways that will feel new and exciting for many. Consider a shot in which the camera serves as Janusz’s eyes, looking through his hands, which make a circle, in order to focus on something far in the distance. The depth of field is shallow and the rack focus is a special effect all on its own.

Unfortunately, nothing else in the film ever becomes as confident or comfortable as the visuals on display. The screenplay feeds monologues to each survivor, explaining their personal tales of past sins to anyone willing to listen. There’s no organic build-up to these moments, they just start talking. These scenes are followed by minutes of little-to-no talking, recalling Roeg’s Walkabout or Herzog’s Aguirre: The Wrath of God. This contrast confuses what exactly Weir’s intentions are. He seems determined to make an Old Hollywood WW II morality tale and a two-and-a-half hour art house epic at the same time.

The film livens up a bit with the introduction of vagabond Irena, played by Saoirse Ronan, who elicits a warmth in these rather cardboard characters that alludes to more dynamism all around. But, alas, she soon becomes just desperate as the rest, allowing the film to fall back into its own confused rut of declarative confessions and silent, ponderous close-ups.

By the time the dwindling group crosses over the Himalayas into India, the film itself seems tired of the story.

Do you plan on seeing The Way Back? What do you think of Peter Weir?