The life of an artist is often pigeonholed into some lofty, depression-laden existence built upon selfish ambitions and creative genius leaving no room for anything else. One could argue the great works possess such high emotive worth and resonant beauty because their creators poured every ounce of their heart and soul into them with nothing to spare on a life with which to love or be loved. Well-known masters were penniless and poor—starving artists who could have used the financial wealth bestowed upon their estates in death to truly live long and fruitfully. Or perhaps any amount of comfort would have only rendered the once abundance of talent and drive sterile, that hunger transferred to the canvas satiated by outside forces instead of the aesthetic grace of the work itself.

Such thoughts lead to the varying concepts of what art means and what falls beneath its umbrella. Some would say life itself is a gift from God—each facet a stunningly unique work of art by some higher being to which we aspire. Most would admit their greatest creation despite achievement is that of a child to carry on their legacy and ideals into the future. Herein lies the conflict for modern-day creative types caught in a balancing act between professional and personal within a career relying upon the coexistence of the two. Labels like sell-out and whore are thrown about when any artist agrees to work on a commission with intent and result beholden to a benefactor, but everyone must draw a line somewhere when the product’s worth no longer serves you alone.

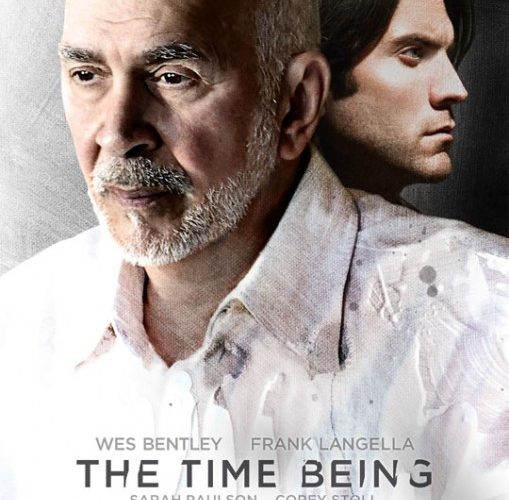

This is exactly where Daniel (Wes Bentley) finds himself at the start of first-time feature film director Nenad Cicin-Sain’s The Time Being. Struggling to keep his head afloat while doing the work his soul demands of him, it’s easy to see the amount of time spent on a gallery show without a guarantee for success can never outweigh the separation building between he and his wife Olivia (Ahna O’Reilly) and son Marco (Aiden Lovekamp) in the process. Falling deeper and deeper into the art becomes nothing more than a lie to himself and his family that the end game is for their whole. That hunger for the unknown—to create from nothingness—clouds his judgment as society’s vestigial concept of male breadwinning warps his mind into forgetting the true meaning of his vocation.

Refusing to escape his head long enough to understand Olivia’s need for the partnership she agreed to when they were married, Daniel simply digs himself deeper from embarrassment, insecurity, and knowing full well his selfishness is what’s fracturing his relationship to a point of no return. Desperate for salvation, he jumps at the chance to meet the reclusive benefactor who buys one of his “still deaths” of staged, rotting food. Warner (Frank Langella) is a stern, matter-of-fact man of wealth who sits in his cavernous mansion alone dictating his wants to those all too willing to serve. Under the assumption he will be painting something for the man, Daniel soon becomes troubled and defeated to accept a job as a hired hand merely filming random events at his new employer’s behest.

From here comes the obvious juxtaposition of both men as one’s unabashed acceptance of his solitude leads to its projection onto the other. Warner seems as though he’s testing Daniel’s mettle to discover whether he has what it takes to be a true artist—to release himself of all other anchors in order to plunge head first into the depths of imagination and God-given talent. Warner makes the painter do his bidding at specific times he knows would be better spent at home with his wife and son or at the job that subsidizes his artistic endeavors. He also never shows remorse when such instruction deteriorates all remaining hope of Daniel turning his life around. But whether Warner does so on purpose or not, it’s Daniel who ultimately chooses his fate.

Both actors exude a severity throughout the film as brooding souls caring for nothing other than themselves, fully conscious of what such a decision means for those around them. And as revelations uncover exactly what Warner has been seeking, we discover just how similar they are. Their performances are analytically cold like the carefully constructed frames in which they exist before family—love lost or soon to be—inspires the emotion in their bodies that it does through vigorous paint strokes on the canvas. It’s an acceptable choice on behalf of Cicin-Sain because the goal of the film is to break through the rigidity into a more fluid state where compromise and humanity can replace the ego so often placed on a medium of such solitary creation. It just sadly may be too much.

The Time Being‘s calculated fabrication does look gorgeous onscreen, but at the same time hinders its audience from truly engaging with the story. There’s a lot to enjoy on a purely visceral level from opening snapshots of Daniel and Sarah putting on their public faces to the meticulous process shots of the art itself to the abstract plumes of colored oil swimming in rinse water but I can’t help wondering if the eventual emotional release was earned. Sarah Paulson and especially Langella—in a powerfully cathartic exhale—shine once hearts prevail over minds, but its abruptness can catch you off-guard. Cicin-Sain and cowriter Richard N. Gladstein thankfully provide few concrete answers as to where their characters go afterwards, but I’m not sure they offer enough for us to care about guessing.

The Time Being is now on VOD and hits limited release Friday, July 26th.