In crafting a series of gripping, mature dramas, the releases from Australia’s Blue-Tongue Films have certainly left a stamp on independent cinema in recent years, with those involved — from Ben Mendelsohn to Joel Edgerton — seeing their careers buoyed. Their latest production, The Rover, comes from David Michôd, and retains certain stylistic sensibilities of his debut, the Shakespearean crime drama Animal Kingdom, while crafting something vastly different.

The Rover immediately succeeds in planting one in the downtrodden world it’s created: ten years after an economic collapse and, needless to say, Australia. By keeping the scale small and the minute details abundant, Michôd effectively sells a barren wasteland full of spare, secluded inhabitants. Leaving the rest of the world’s fate to our own imagination, it’s a far more powerful in approach than anything a fabricated news broadcast or prologue could attempt to convey.

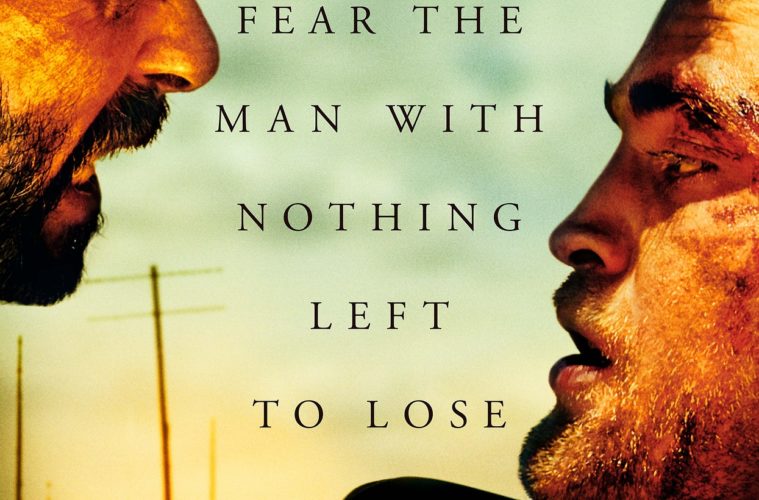

The specific story here — and it’s very specific — lies with Guy Pearce as an exceptionally weathered, drifting loner named Eric. He seems to know his way around the area when we drop in on him, companion-free, grabbing a drink at a local bar. Michôd then cross-cuts to a gang running from a mishap, where we learn the group’s leader, Henry (Scoot McNairy), has left his brother, Rey (Robert Pattinson), to die. These two threads briskly connect when the gang is forced to steal Eric’s only possession, a beat-up car, and he begins tracking them down with the rejected member’s assistance. While an early, well-choreographed chase sequence and a few shoot-outs might have one thinking of Mad Max, Michôd’s latest is far removed from action staples, the writer-director instead much more interested in looking at the complementary (but often-volatile) relationship between Eric and Rey, perhaps the first of its kind Eric has had since the collapse.

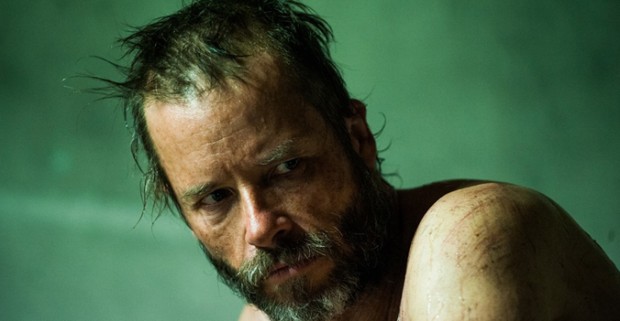

Pearce imbues his character with a penetrating deadness, keeping us on guard as to what exactly he’ll do next; this uneasiness is complementary to Michôd’s controlled construction of a dangerous environment where violence could strike at any time. Paired with Pattinson — who gives a committed, twitchy, and altogether daring performance as a “halfwit” — this compelling balance is our purview for much of the runtime. One has endured the hardships of the collapse his entire adult life, while the other is caught in the middle, and this dichotomy is perfectly captured in an idiosyncratic, ultimately haunting rendition of Keri Hilson‘s “Pretty Girl Rock.”

Michôd’s conjuring of mood in a potential near-future is impressive, as is the aforementioned relationship at The Rover‘s center, but the general arc of their journey doesn’t deliver as much impact as one might expect. While a few reveals as to what led these two individuals down this path go a long way, their actual journey and the conversations therein sway too minimalistic to be of crucial significance. While building towards an ending that’s sure to be divisive — and one that I admired — we’re briefly introduced to a variety of supporting characters and their struggle to survive in this world. From a peculiar brothel to spare military presence to a new iteration of a gas station, all these details make for a more interesting narrative than the fairly cryptic, albeit standard one at this picture’s center.

Adding to the engrossing performances, the terrifically unconventional score by Antony Partos (recalling Jonny Greenwood’s work on There Will Be Blood) and Natasha Braier‘s yellow-tinged cinematography both do wonders to sell this world. A bleak, spare look at justice in a desolate landscape, The Rover will most certainly not be what one expects following Animal Kingdom, but Michôd has created a frighteningly realistic apocalyptic western that’s entirely his own.

The Rover opens on June 13th.