For a genre film, The Rite takes the subject matter of faith as seriously as it can while retaining mainstream appeal. If it were to dive either way we might be in propaganda film territory. This is one of many textures effectively employed by Mikael Håfström, who previously directed 1408, a Steven King adaptation which bucked the trend that all Stephen King adaptations not directed by Stanley Kubrick and Frank Darabount (with the exception of The Mist) suck. What sets The Rite apart is the film’s textures; this simply isn’t light and shadows that add up to cheap jump scenes. The film takes a somewhat more unexpected high ground and ponders the same question I have about exorcism: are those in need of an exorcism mentally ill? Is the approach helpful or harmful?

Enter young priest Michael Kovak (Colin O’Donoghue), a mortician’s son who appears destined for the family business from the film’s skillful opening sequence of Kovak at work. It’s reminiscent of the recent Japanese film Departures. Fearing a lack of faith, Kovak is drawn to a Catholic university, at odds with his faith. He attempts to resign before God sends him a signal in the form of a chain reaction he sets off. He is recommended by his mentor, Father Matthew (Toby Jones), for an experimental program at the Vatican to re-teach the clergy the little-used rite of exorcism.

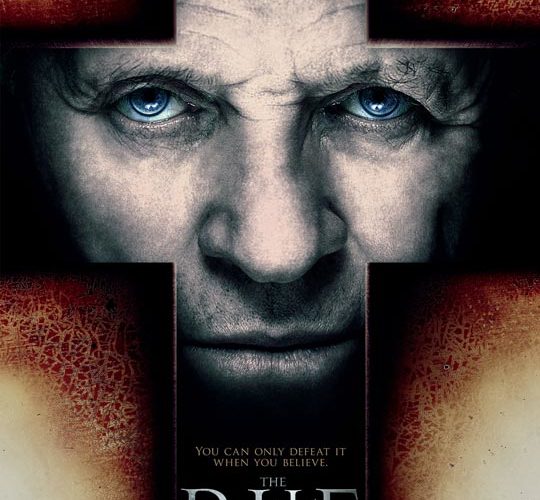

Paired with rouge priest Father Lucus Trevant (Anthony Hopkins) he learns the ropes with a focus on youth – perhaps demons consume those untreated before they reach age 30 – that might be one interpretation of Black Swan. On the beat is a journalist, Angeline, played by Alice Braga – rare that the Vatican would allow a journalist inside given the secrecy and shame in the Church in recent years. The film subtly acknowledges a clergy crisis: the average age of nuns and priests is on the rise, the church needs young talent such as Michael.

Exorcism has been a popular theme in recent years with two versions of the same prequel to the Exorcist (Exorcist: The Beginning by Renny Harlin and Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist by Paul Schrader), The Exorcism of Emily Rose and The Last Exorcism to name a few – each with their own take. The Last Exorcism from last year asks the same questions Kovak asks: is there a period in which religion trumps common sense? Are these psychological issues that could easily be treated with proper therapy or is exorcism a form of therapy. It certainly couldn’t be any worse than Dr. Phil – as both an exorcism and a Dr. Phil intervention involve yelling at the subject to solve their problems. Trevant counters, “it’s the demon that’s in pain.”

Lacking the aspirations (and perhaps the perversity) of filmmakers who dare to skewer religious iconography such as Alejandro Jodorowsky and Pier Paolo Pasolini, and the propaganda elements of Christian-produced action films (often starring Kirk Cameron) – it takes the middle ground. It assumes evil is a real thing and its treatment of Satan, informed by top-notch production design and direction, is effective. If only it had the gall to have a real and potentially offensive conversation on faith it would break free from the conventions of genre and achieve a level that William Friedkin’s The Exorcist did.