It may be called The Quiet Ones, but the latest supernatural offering from revamped Hammer Studios is anything but. John Pogues would-be chiller may not raise the hackles with effective scares, but listening to it is an aggressive assault on the senses. The soundtrack sounds like the musical stylings of Stomp! as led by Quasimodo and the Phantom of the Opera. If you’re planning to see a movie in a theater near to The Quiet Ones, be prepared for some potential poltergiest interference from the film next door.

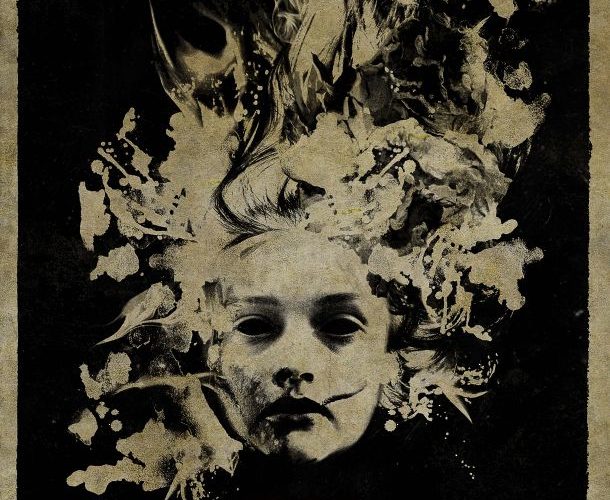

That kind of gothic pomp and circumstance isn’t happening at just the decibel level of The Quiet Ones; from the gaudy 70’s kitsch and costuming to the computer-generated manifestations, this is a movie that weilds its style like a blunt instrument (a Hammer, maybe?). This factor will only be unpleasant for some, with fans of the British studio’s older output remembering that for Hammer, style was every bit as important as substance. That excess crawled all the way down to the usually over-heated performances, and The Quiet Ones gives us a few cackling turns of its own, most notably Olivia Cooke as a possibly possessed waif and Jared Harris gunning for the Peter Cushing award of excellence as the ambitious but sinister professor who’s experimenting on her. The problem with Pogues’ film is that it never thrills or spooks us; when there are so many paranormal thrillers out there, it takes some real rattle-and-clank to get the attention of anyone with a beating pulse. This one floats right through the eyes, past the brain, and out the other side with little more than a whiff on the old neurons.

The considerably creepy premise holds plenty of eerie value, some of which is later squandered for creepshow theatrics. When Harris’ Prof. Joseph Coupland loses his university funding, he does what any stable and resourceful science type would do, he heads out to a derelict manor in the countryside with a few student researchers and a highly unstable test subject. What he’s looking for is the scientific truth behind cases of possession and paranormal activity. Coupland believes that men and women like young Jane Harper (Olivia Cooke) have the ability to manifest their own energy telepathically and this resulting force is responsible for classic ghost-and-devil related phenomena. If one could channel that negative energy into a physical object and destroy it, then the patient would be mentally cured, and in a sense, exorcised by science. Coupland also has the religiously-inclined Brian McNeil (Sam Claflin) along for the ride as the cinematographer of his little experiment, and many of those scenes have the unconvincing verve of the over-played found-footage genre. There are many appealing elements to the story, but they end up sidelined by the excessive genre trappings that clutter the second half. I found myself thinking back to the real-world experiments that influenced the film and wondering if they wouldn’t have been creepier than the manifested digital bogeyman that comes pouring out of Harper like a snarl of evil Twizzlers.

The mumbo-jumbo that accompanies The Quiet Ones is an attempt to add a disquieting period-piece authenticity, but it feels like homage rather than pertinent historical context. Like the superior The Conjuring, the film gets much mileage out of the tunes and fashions of the era, and it even cashes in on that 70’s aura of complicity with the occult. When Harris’ Coupland raves passionately about the extent of the experiments, we can almost visualize the chapter set aside for him in the Time Life book series dedicated to haunted houses. Harris, all craggy bluster and intimidating sophistication, would not have been out of place in the early days of Hammer and his presence here bolsters the creeping atmosphere for longer than expected. His odd, intense chemistry with Cooke is also a highlight, and if there’s anything particularly convincing in the film it would be the battle of wills that Coupland and Harper engage in when the latter feels her persona threatened by the former. Claflin, good in the last Hunger Games film, is decidedly subdued here and doesn’t offer the same kind of high-energy necessary to ground the quirkier aspects of the tale.

Every person has that certain movie setting and genre trope that you’re powerless to resist. For me, it’s haunted houses; creaking staircases, bleeding wall spots, and whispered voices on the empty alcove are a few of my favorite things. When done right, these particular elements give me a powerful sense of cinematic comfort. They are, for lack of a better descriptor, my version of a back-porch rocker and a tall glass of lemonade. As a result, I enjoyed The Quiet Ones to a certain degree. If you share my predilection for well-worn haunting antics, you might too. It’s well made and serviceably atmospheric, and there’s a handful of good moments. Ultimately, it’s all just a little too comfortable. Even before things started sliding towards the demonic, I found myself growing restless with the film and its obligatory, easily telegraphed twists. The jump scares are so heavy-handed they feel laughable, and they mutilate any slow-building moodiness Pogues has established up to that point.

Like Mike Flanagan’s recent Oculus, another horror thriller that pulls one rug too many out from under the audience, The Quiet Ones ultimately feels irrelevant. There’s a line it crosses, from collaborating with our imaginations to freak us out to jerking around our expectations and frustrating us with false moves. You can enjoy Harris’ performance, the strobe-lights, the obligatory menacing doll, and the Linda Blair shenanigans that Crooke gets up to, but none of it is in service of a well-built narrative and there’s no amount of posturing that can hide that. This new film’s closest cousin is probably the Richard Matheson penned The Legend of Hell House, which itself updated some of the tricks and treats of Robert Wise’s adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. Hammer alumn John Hough (Twins of Evil) gave Hell House the corrupted spiritual rot and tingling psychological fear that Quiet Ones misses. No matter how wince-inducing the violin strings get or how much CGI spews out of Cooke’s face, nothing here matches the low-key scene in that film where a possessed Gayle Hunnicutt snarls a hypothetical orgy of seduction at a gob-smacked Roddy McDowell. It’s not about how many resources you have, it’s making the best use of the ones you’ve got. Moving forward, that’s a lesson new Hammer could take to heart.

The Quiet Ones is now playing in wide release.