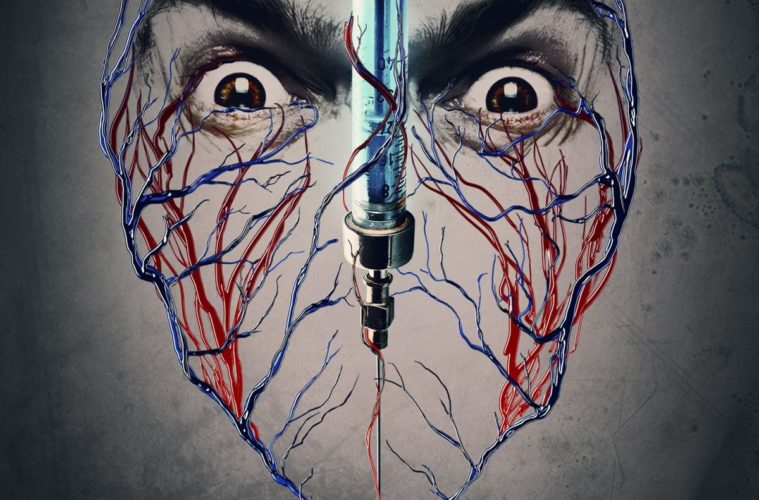

Between Midnight Special, Netflix’s Stranger Things, and now Joe Begos’ The Mind’s Eye — a virtual remake of David Cronenberg’s 1981 film Scanners — the ’80s genre landscape has gotten substantial representation on 2016’s screens. But whereas the first two cleave closer to the Spielbergian trademark of generating wonder through restraint, Begos dives headfirst into nastiness and excess, sharing some of Stranger Things’ Carpenter DNA while fitting the title of the Jeff Nichols’ picture better than its actual owner. Indeed, The Mind’s Eye is midnight movie material, a film whose nightmarish bloodletting surpasses disgusting to skirt on the edge of the sublime. As cinema, the film’s influence likely won’t last given the disproportionate amount of time and energy it spends on revisiting old body horror tropes instead of crafting compelling characters and an original story. Still, emerging from the aesthetic doldrums summer cinema typically brings, the sheer insanity of The Mind’s Eye is a welcome anomaly.

The plot of the film resembles Scanners’ from the get-go: a nondescript wanderer named Zack Connors (Graham Skipper) gets pursued by authorities for unknown reasons and, after his hand is forced, nearly kills someone with a fearsome display of telekinetic power. After being arrested, Zack ends up in the custody of Dr. Michael Slovak (John Speredakos), a mad scientist who experiments on telekinetic individuals and forces their cooperation via a serum designed to temper their abilities. When Zack escapes Slovak’s compound with Rachel (Lauren Ashley Carter), a fellow telekinetic and a love from his past, Slovak deploys his men to retrieve them, resulting in various déjà vu-inducing moments such as a splattery shot of a head exploding and an epic staring contest between telekinetic combatants.

The risk of homage is that the tribute-paying film might never escape the shadow of its influences. Appealing to nostalgia can only get a film so far—if the present movie isn’t distinctive enough, it will remain only a conduit to past classics rather than becoming a worthwhile destination in and of itself. The Mind’s Eye doesn’t quite avoid the temptation to imitate rather than innovate, and in this regard, the film disappoints. Instead of mobilizing genre tropes in service of an original story with distinctive characters, the film seems to have reversed the order of operations: it has chosen to inhabit a genre (or, more accurately, another film) and half-heartedly invented characters and a plot to meet that goal. It channels Scanners, but doesn’t fully transcend it.

The film’s saving grace is its outrageous barbarity, which, though in itself not breaking any new ground given its obvious indebtedness to the midnight movie brand of carnage, nonetheless feels refreshing when applied to the Scanners narrative framework. For despite Cronenberg’s notoriety as the king of viscera, Scanners was actually in large part an exercise in restraint. A couple scenes aside, the most gruesome deaths in that film occurred offscreen, with visible gore seldom exceeding bloody gunshot wounds. Although Cronenberg introduced characters with great destructive power, he kept much of that destruction from view, suggesting horror more often than depicting it.

If Scanners built anticipation through holding back, The Mind’s Eye is the release: an orgiastic answer to 35 years of wondering just what the Scanners could have done if the gloves really came off. They come off big time in The Mind’s Eye, and with them come heads, torsos, and appendages of various sorts. As the Slovak persuasion meet more telekinetic resistance than they expected, people are shot, stabbed, dismembered, and disemboweled in pretty much every way you can imagine and a few you probably didn’t think of; most of the film’s action scenes turn rooms into life-sized Jackson Pollack paintings fashioned from the blood of victims’ innards. By taking the violence in Scanners to uncharted heights of gory delirium, Begos’ film manages to do through brutality what it didn’t do through storytelling: it creates an identity for itself apart from its inspiration.

Having demonstrated this strain of novelty, The Mind’s Eye actually grows more distinctive with each new reference it makes. Each moment of homage reestablishes and strengthens the film’s kinship to the Cronenberg picture, but each subsequent blast of savagery wrests artistic control away from the specter of the Canadian auteur to fulfill Begos’ particular reimagining of the Cronenbergian Scanner-verse. In other words, it is precisely the interplay between old and new that crystallizes the status of The Mind’s Eye as a revisionist take on a canonical work of horror cinema. Though the film misses the opportunity to flesh out its alternative vision through character depth and narrative idiosyncrasy, its innovation through violence is a sight worth seeing.

The Mind’s Eye is now available on VOD and in limited release.