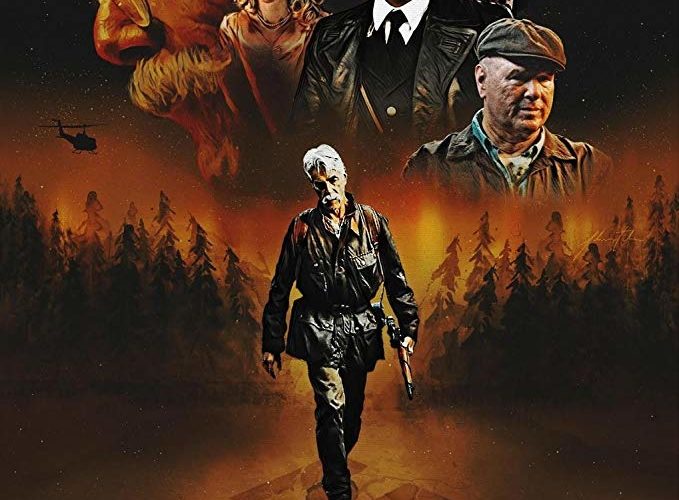

If there’s one thing The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot does right– aside from kill Hitler, of course–it is putting the fate of humankind in the hands of Sam Elliott. This turns out to not be the only thing first-time writer-director Robert D. Kryzkowski succeeds with in this bizarre, charming, and sad tale, but it is certainly the epicenter of its triumphs, and the polar opposite of its shortcomings.

In each and every frame, Elliott captivates us as Calvin Barr with subtlety and ease, physicalizing the sensations of regret and age and sheer goddamn exhaustion without ever letting you see him try. He just is; he exists and carries the weight of a man who, in years past had modest aspirations of love, but who—as the years rolled past like the train that perhaps carried him behind enemy lines during The Second World War—discovered that father time and the ever-plotting government had other plans for.

We meet Elliott’s Barr as a veteran in a small town, inhabiting bars and feeding his dog, seemingly leading a simple life. Yet under the surface, past the sheen of an old man lost in his thoughts, is a war veteran continuously brought back to years in the service (and played here in the past by Aidan Turner). Though PTSD-driven flashbacks are well-covered ground in cinema, there is a matter-of-factness here that feels like it scratches some sort of truth; the way these memories might happen not in moments of silent reflection, but instead interrupt your daily routines and come from the slightest of signifiers.

This sensation, the undercurrents of regret and historicity, speak to the film as a whole—even in moments of almost cute humor, or during its most conceptually (and formally) gonzo segments, The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot is laced with melancholia. There is a weight to it, in its structural and scene-by-scene pacing, in its movements. Even the occasional whip-snap editing Kryzkowski employs feels like a lurch forward through some sort of cosmic force, a sensation that is perhaps necessary yet goes against the atmosphere of Barr’s life, like having to be amiable or even talkative at a convenience store when all you have been considering—and still are considering, after the quick rush of an interaction is over, and your social niceties recede—is how something just doesn’t fit right today.

Indeed, this brief editing technique is first utilized during one of the extended flashback scenes, as if to suggest its energy comes from a much younger man with intentions and a mission and a purpose, not yet down-trodden by an act of murder or getting caught in the cogs; still hopeful for budding romance and happily-ever-afters.

Later, when a similarly energetic technique is used (to build to arguably the film’s best line), Elliott’s exhaustion and matter-of-fact tone punctuates and accentuates the dichotomy of the film’s two timelines. Like these discrepancies of Barr’s age, the film as a whole may not entirely reconcile its techniques and imagery, but it is definitely an intriguing mixture.

Current-day Barr drives into town with his dog and contemplates the now: “Terrible stuff, Ralph. That’s all we know, and we eat it up.” Here, in this cinema, there is perhaps no tidy resolution or job well done wrapped up with a bow. Killing is still killing, and even with a righteous cause, that very well might take a toll on your soul.

This idea touches on one of the most interesting points—illustrated most directly in Elliott’s best monologue—in The Man Who Killed: the idea of stripping away myths and mythic figures, while still noting the monumental and real-world impact their ideas may still have. Not the man, but the costume. The guise.

While these elements most struck me, they are undoubtedly packed into a film that might suffer from some first-time marquees: protracted dialogue without real purpose, stilted editing, and a general direct-to-video aesthetic that, while not inherently a shortcoming (far from it, in fact), doesn’t seem to entirely mesh with the film’s pacing, focus, or ruminations.

None of this is to even mention Bigfoot, who, without spoiling the entire affair, leaves a rather surreal and dissociative impact, yet is also not particularly impressive. This is not a slight, per se, as Bigfoot’s presence ties nicely into The Man Who Killed’s idea of the entity behind the myth. Furthermore, it might even speak to the way rumors and passing time aggrandize figures for both our detriment and theirs. It’s a film full of interesting ideas, all wrapped up in messy, even shoddy methods, and an undeniably sincere and rather astonishing performance from Sam Elliott, who doesn’t seem to give a hoot whether he’s hunting Bugs Bunny or the Oscar gold–he’s just going to go for it, dammit.

The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot opens in theaters and on VOD on February 8.