As Les Standiford’s book would tell it, Charles Dickens (Dan Stevens) found himself in somewhat of a creative rut after a lengthy and expensive tour of America post-Oliver Twist. He had published three flops since buying a new London home in need of wholesale remodeling and began watching his pocketbook dwindle along with his confidence. It was as though the autumn of 1843 presented him a make or break moment wherein he wasn’t certain he would ever write again. And then inspiration struck with the voice of a new maid (Anna Murphy’s Tara) telling the children Irish ghost stories before bed. This idea of Christmas Eve providing a doorway of sorts to the spiritual world planted itself in Dickens’ mind. Soon after Ebenezer Scrooge (Christopher Plummer) was born.

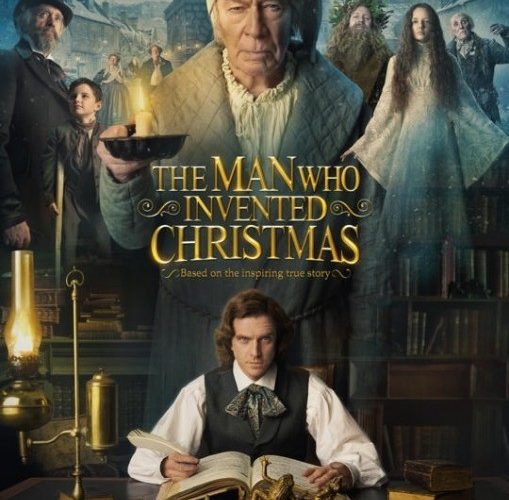

The last thing anyone needs in 2017 is another adaptation of A Christmas Carol — especially since none have ever come close to the brilliance of Brian Desmon Hurst’s 1951 version starring Alastair Sim). But what if we received one in the fringes of something else? What if we were given a new Scrooge as muse, a crotchety old miser haunting Dickens as he struggles with writer’s block to start, finish, and publish his latest novella in just six weeks time to be ready for Christmas? It would be a biography of the author, an adventure through the psyche of a literary genius as he mines the fears, insecurities, and hopes for the future of his own life. Scrooge would therefore be a mirror: on society and Dickens himself.

This is what Bharat Nalluri’s The Man Who Invented Christmas delivers. Adapted from Standiford’s book by Susan Coyne, we meet the genially charitable Dickens on the cusp of self-implosion. The one thing he’s unable to forgive — his father (Jonathan Pryce’s John) being sent to debtors’ prison and therefore leaving Charles to work in a factory as a child — is exactly what may happen to him if this gamble doesn’t pay off. He tells his wife (Morfydd Clark’s Kate) and best friend/”agent” (Justin Edwards’ John Forster) that life is expensive. Dickens says this because he’s overcompensating for a poverty-stricken past that still haunts him. She’s happy to live modestly and Forster’s son-of-a-butcher merely seeks the love of his fiancé. No one needs Dickens to be a “gentleman” but him.

And it’s all riding on this book’s success. He’s taken a loan to hire an illustrator (Simon Callow’s Leech) and desire the finished work to be decadent in a way that rides the coattails of a Christmas holiday just recently coming into fashion with the Royal Family’s adoption of Germany’s “tennenbaum” tradition. Not only must he submit the manuscript on time, he must also sell every copy just to break even. Add to that stress a sick nephew, four children of his own with a baby on the way, and a dependent father he seems to resent more than love and even Dickens finds himself a loss for words. Thankfully his characters have begun to spring to life around him, their existence a sign something will turn up.

The result is a charming look behind a story we know and love. You can’t help allowing a wry smile to form on your face upon hearing Dickens’ publisher speak ill of his clerk’s use of the holidays as a reason to take a day off. You’ll chuckle when some wealthy aristocrat stops Dickens after a charitable appearance to speak of the virtues of workhouses. And it’s only too perfect when an elderly waiter named Marley stops at his table to take an order, the name quickly jotted down in Dickens’ notepad for future use. Maybe some of these anecdotal scenarios are true and maybe most are not. All I know for sure is that they’re fun to experience alongside the light bulb moment of inspiration they conjure.

The best part, however, is acknowledging how these external characters of greed and oppression only provide Dickens with dialogue to use. Scrooge may walk beside him to regurgitate each line and cement the fact that he’s a cruel monster deserving of everything the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come throws at him, but he isn’t real. The filmmakers pull no punches as far as representing Charles and Ebenezer as two sides of the same coin — the former’s incredulity at the selfishness of others a public face to mask the latter’s unforgiving nature thanks to not wanting to ever be let down again. John Dickens becomes the bridge between these opposing faces, a man who inspired Charles with his optimistic phrases and destroyed him irrevocably when he went away.

We’re watching as Dickens discovers whether a man like Scrooge can be redeemed. Could someone so coldly callous be converted in but one night? Could the magic of Christmas work to change the prevailing nature of man? So while we are ostensibly getting another rendition of A Christmas Carol after all, there’s something about Dickens being the one awakened by his own story (that’s awakened many others) that resonates more than you’ll expect. Not every Scrooge is so overtly stingy as the caricature written. Many do what he does with a smile on their faces and entitlement bred from confidence rather than anger. Just because Charles Dickens was a massive celebrity doesn’t mean he didn’t harbor demons. Even the best and most beloved of us lose our way.

Stevens excels at playing put upon characters mired in self-doubt with both heavy drama and infectious humor (see Legion for another great example). He deftly pulls off the necessary instantaneous shift from frustration to epiphany very well, his kinship to Tara as a storyteller/reader the perfect foil for his abrasiveness and mistrust towards a father doing his best. Sometimes those attitudes swap with volatility, Dickens’ desire to surround himself with the specters of fictional characters speaking to him greater than those he loves and fears never understand him. Plummer is therefore a delight when poking this bear with mischievous relish and Pryce a scene-stealer when poignantly yet futilely trying hard to put his mistake behind him. More often than not ghosts aren’t needed because we haunt ourselves.

The Man Who Invented Christmas is now playing.