A funny thing happened at some point in these past few years: Wes Anderson became embraced once more. While America’s tidiest teller of tragicomic stories had never fallen entirely out of favor, there persisted the narrative of a now-too-tidy aesthete consuming himself from the inside out, the curiosities practically inherent to ventures under the sea and across the Indian countryside be damned. (“They’re starting to feel like diorama displays writ large,” as we’ve all heard, these claims — while, yes, not without any merit whatsoever — feeling fairly of the same stripe as “it’s as if someone just filmed a stage play.”) Yet the most recent pair have clearly shifted perceptions awfully quick, with only the most stone-hearted of stone hearts finding some emotional and intellectual deficiency in Fantastic Mr. Fox — the closest any American director has come to stylistic self-actualization this side of the 21st century — and Moonrise Kingdom, both his most complete work and, it’ll be alleged herein, an out-and-out masterpiece that allowed his formal proclivities and genteel witticisms to congeal like the workings of a fine grandfather clock.

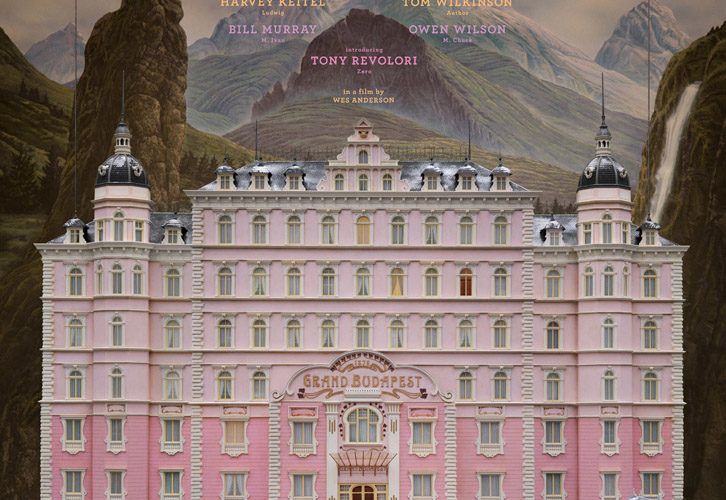

At this “peak” state, it’s at least a bit fitting to receive something which feels as if he’s been working toward from the first day. In The Grand Budapest Hotel we can sense both a progression and summarizing of the entire Wes Anderson canon: an immediate, overriding narrative and stylistic conflation of The Royal Tenenbaums’ literary qualities and Moonrise’s storybook leanings; the bandit antics of Fox; Bottle Rocket’s rabble-rousing spirit; the looming ghosts of never-to-be-recovered loved ones which so significantly drove Rushmore; The Darjeeling Limited’s always-searching eye for foreign landscapes; even, at its climax, The Life Aquatic’s gun fight. Yet despite the clear consistency in form, structure, theme, tone, and sensibility which run through them all, The Grand Budapest Hotel has the quality of being often overstuffed, at once emotionally devastating in a manner few outside his corner have seemed to master and, yet, the slightest bit slack in fulfilling much of a cogent throughline.

At this “peak” state, it’s at least a bit fitting to receive something which feels as if he’s been working toward from the first day. In The Grand Budapest Hotel we can sense both a progression and summarizing of the entire Wes Anderson canon: an immediate, overriding narrative and stylistic conflation of The Royal Tenenbaums’ literary qualities and Moonrise’s storybook leanings; the bandit antics of Fox; Bottle Rocket’s rabble-rousing spirit; the looming ghosts of never-to-be-recovered loved ones which so significantly drove Rushmore; The Darjeeling Limited’s always-searching eye for foreign landscapes; even, at its climax, The Life Aquatic’s gun fight. Yet despite the clear consistency in form, structure, theme, tone, and sensibility which run through them all, The Grand Budapest Hotel has the quality of being often overstuffed, at once emotionally devastating in a manner few outside his corner have seemed to master and, yet, the slightest bit slack in fulfilling much of a cogent throughline.

The seems odd considering the narrative’s cut — or one of them, really; it’s actually contained inside a novel which, itself, relays the experience of being told said narrative, to say nothing of two additional layers (more on this later) — is very much Anderson’s jib, its incidents and their relationships with one another often coloring within the lines of what we’d imagine to be detailed in many a book stolen by Suzy Bishop. As set in place by a Tilda Swinton-portrayed reference to the great Max Ophüls — he may craft films like no one else, but Anderson’s pictures feel like they’re inspired by nearly everyone else — Budapest’s central beats operate with a zig-zag character that efficiently service his leanings as an aestheticist, somehow still failing to wholly behoove his impulses as a scribe, the latter falling into Life Aquatic-esque issues regarding complete consistency in focus amidst an otherwise-terrific ensemble. It’s as if events were progressing from one point to the next with little in the way of the helmer’s usual concern for total cohesion, very likely an effect of his plottiest film yet: squabbles over an inheritance, imprisonment, an escape, further squabbles within these, their inevitable cohesion into a setpiece — much is packed into no more than 100 or so minutes, eventually to the point of exhaustion.

It’s nevertheless with great admiration that I recall his most ambitious structure yet, that its share of complexities and unspoken implications shouldn’t infringe upon the necessities of any given moment. Despite it being advisable to truly experience this multi-tiered gambit within the context of much else that occurs — and despite two of four timelines only having been granted a rather limited amount of screentime — one must address a gesture that stands among the most intensely personal notes Anderson has ever struck. They present a new way of seeing his immaculately designed worlds, either stretching or conjoining character relationships in a way that’s more revealing of careful progressions in tenor, tone, and various, ever-careful juxtapositions than we’d think him capable of letting on.

It’s nevertheless with great admiration that I recall his most ambitious structure yet, that its share of complexities and unspoken implications shouldn’t infringe upon the necessities of any given moment. Despite it being advisable to truly experience this multi-tiered gambit within the context of much else that occurs — and despite two of four timelines only having been granted a rather limited amount of screentime — one must address a gesture that stands among the most intensely personal notes Anderson has ever struck. They present a new way of seeing his immaculately designed worlds, either stretching or conjoining character relationships in a way that’s more revealing of careful progressions in tenor, tone, and various, ever-careful juxtapositions than we’d think him capable of letting on.

The 4:3 frame, used most frequently between Budapest’s four settings, may, too, be the biggest limit he’s yet put on himself: these images require a level of physical intimacy extending past even the sort he’s been fairly keen on in efforts past, and in acknowledging even some necessity to cut off views of the elaborate designs which go hand-in-hand with a Wes Anderson “brand,” playing to almost making a wink and a nod. One might expect the 2:35 frame of his second layer (or third, depending on which order we’re counting) to “compensate,” in some sense, but it’s another stage of formal advancement: these wide images adhere to a visual fabric in which it can be sensed, through particular pans and cuts, that Anderson has decided to explore both cinematic space and the camera-eye’s own opportunity for investigating it with more thoroughness than some collected memory of his oeuvre’s long-ingrained aesthetic sense might lead one to anticipate. (Note the opening of space when Jude Law’s writer is first told of F. Murray Abraham’s Zero, the composition patterns between either in their first true encounter, or alternate stretching and crushing of bodies in various dinner-table two shots.)

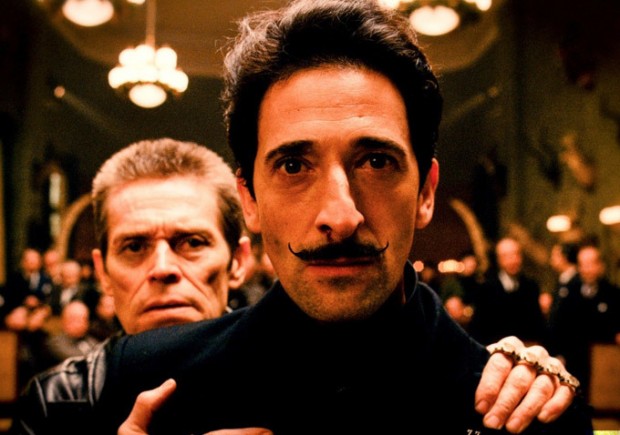

Budapest proves funny in the way people expect Wes Anderson to be funny, though moment-to-moment plays with comedy show more success as a maker of the small moments which render an affection for an ensemble’s rhythm all the more fitting: whereas Adrien Brody’s jilted heir can amuse with the hugely profane or, to a similar end, Willem Dafoe delights with the shockingly violent — a few incidents and images not feeling so out-of-place in a horror film — there’s an unrepentant sweetness to onscreen turns from the film’s true lead, Tony Revolori, and Saoirse Ronan which avoids any tonal incongruities from one well-dressed and fine-coiffed character to the next. As the sole writer and director, a career first, Anderson fully mines his scenarios for a conflict between words and images; situated in and amongst the titular hotel, spoken traces of a dark past might escape one’s ears as the eyes are perpetually engaged, while the comedy inherent to a line and its reading fly in the face of, during one such instance, a severed head. (This is in addition to some severed fingers and one shot that recalls Moonrise Kingdom’s biggest shock.) It’s a shame that some of the larger setpieces — e.g. a prison break that felt more lively when animated years ago, or a soon-to-follow chase scene that, while well-orchestrated in essentially every manner, rings almost indescribably anemic — barely register as comedic beats, in turn largely underscoring a curious shapelessness in the film’s center.

Budapest proves funny in the way people expect Wes Anderson to be funny, though moment-to-moment plays with comedy show more success as a maker of the small moments which render an affection for an ensemble’s rhythm all the more fitting: whereas Adrien Brody’s jilted heir can amuse with the hugely profane or, to a similar end, Willem Dafoe delights with the shockingly violent — a few incidents and images not feeling so out-of-place in a horror film — there’s an unrepentant sweetness to onscreen turns from the film’s true lead, Tony Revolori, and Saoirse Ronan which avoids any tonal incongruities from one well-dressed and fine-coiffed character to the next. As the sole writer and director, a career first, Anderson fully mines his scenarios for a conflict between words and images; situated in and amongst the titular hotel, spoken traces of a dark past might escape one’s ears as the eyes are perpetually engaged, while the comedy inherent to a line and its reading fly in the face of, during one such instance, a severed head. (This is in addition to some severed fingers and one shot that recalls Moonrise Kingdom’s biggest shock.) It’s a shame that some of the larger setpieces — e.g. a prison break that felt more lively when animated years ago, or a soon-to-follow chase scene that, while well-orchestrated in essentially every manner, rings almost indescribably anemic — barely register as comedic beats, in turn largely underscoring a curious shapelessness in the film’s center.

But I continue to be so fascinated by its unimpeded angle toward humanity’s worst capacities, and, in the context of a slightly airless comic delivery, at times forced to ask how much Anderson would’ve preferred this as a total point of focus in lieu of Ralph Fiennes’ terrific mugging. It’s hard to escape when the angle is instilled early, as Budapest begins with a title card that introduces Zubrowka — a European nation which was “once the seat of an empire” — and, with its lively font and unprompted positioning as some pace of better days that have since past. This is also a green light: from the first images — those familiar with Anderson’s most recent films will notice a trend in the lateral establishment of visual spaces; it’s becoming a welcome note as singular as anything else up the man’s sleeve — are we aware that something has not only changed, but degraded. Although we’re never introduced to the person whose curiosity for stories begins this particular one, a need to return to some brighter time, just before an onset of destruction, can be parsed from the design of what, one can only assume, is the modern-day Zubrowka (or its basic equivalent). The later, direct analogue to humanity’s greatest atrocity is all the more touching for avoiding direct aural connotations, instead allowing the associations of history — our history, one built on identification through aesthetics and images — to bind the true and the imagined until, like both the film’s interlocutor and observer, we can neither tell the difference nor express much concern as to how or why they should even be distinguished.

This having stuck for more than a week after my initial encounter, I remain hopeful that, like much of Anderson’s work, The Grand Budapest Hotel can only grow in estimation as I grow older — if not any wiser, still more open to the experiences and tragedies life is asking we accept while years pass by. As far as step downs from a career-best delivery go, I’ll take its attempts to at once encapsulate and expand both a full oeuvre and its entire pathology in stride. By now, Wes Anderson doesn’t seem the slightest concerned with anyone’s critical leanings; there’s that much to be thankful for.

The Grand Budapest Hotel will enter limited release on Friday, March 7th.