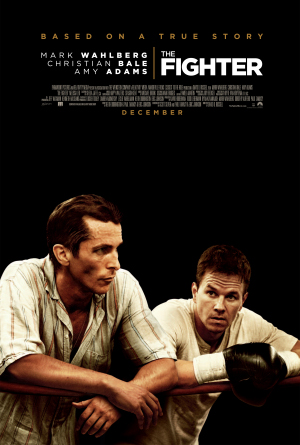

Like every David O. Russell film before it, The Fighter, starring Mark Wahlberg, Christian Bale, Amy Adams and Melissa Leo, is an aggravatingly uneven and impressively ambitious experience. Telling the real-life underdog story of welterweight boxer “Irish” Micky Ward (Wahlberg), Russell’s determined to make a boxing film we haven’t seen before. Something more along the lines of Jim Sheridan‘s The Boxer, in which the boxing serves as a plot device for bigger conflicts, bigger themes.

Don’t be mistaken, there’s a lot of fighting in this picture. In fact, there’s fighting between everyone in Micky’s mile-long family, from his mother (Leo) to his father (Jack McGee) to his crack-addicted brother Dicky (Bale). The family bonds are as strong as they are poisonous. Dicky once knocked Sugar Ray Leonard down – in 1978. He reminds the people of Lowell, Mass. (he’s nicknamed ‘The Pride of Lowell’) almost as much as the people of Lowell remind him. This is 1993, and Dicky’s high enough all the time to convince himself the HBO crew following him around is shooting a documentary about his boxing comeback rather than his out-of-control drug addiction. Here Bale gives the kind of over-the-top performance both the critics and the public will swallow up simply because of how much of it is stuffed down their mouths. It’s Al Pacino in Scarface or Leonardo DiCaprio in Blood Diamond. Everything about Bale is so theatrical it cannot be ignored. It’s at once infuriating and endearing. Dicky’s living in a dream world, and Bale’s living right there beside him. Whatever acting Bale doesn’t have time to do, Leo takes care of. The stark opposite of her slow-burn desperation in Frozen River, Leo’s Alice is hot fire: two parts Medea and one part Jacki Weaver in Animal Kingdom. At one point, she literally hurls a frying pan at her husband’s head.

Over the end credits real footage of the real Micky and Dicky play. Micky, at one point, says “see what I mean when I say I can never get a word in.” He doesn’t get another word in, because Dicky interrupts him. True to life it would seem, Wahlberg offers up one of his strongest performances in some time, adding layers to his little ditty of a turn in Disney’s Invincible a few years back, but no one will notice (God knows you can’t blame them). Even still, Wahlberg’s reserve saves the film from straight parody.

But then Russell always toes the line between reality and absurdity. Flirting With Disaster was a slapstick comedy amidst real problems like unexpected parenthood and responsibility. Three Kings made jokes about stepping on mines in Iraq minutes before one of the characters stepped on a land mine. I Heart Huckabees mashed all of it together and called it existential.

It’s somewhat of a narrative trademark, and the director’s attempt to bring it mainstream is commendable. Groans of annoyance call out from the audience during every family scuffle that occurs, and there are plenty. Thousands upon thousands of eyes will roll every time Dicky gets himself, and his brother, into some sort of trouble. Cliche lines like “he’s my brother, he taught me every I know” are uttered over and over with the kind of sincerity only a Priest could convey, so they must be laughed at. Thankfully, it’s a film fully aware of the comedy inherent in melodrama. Every groan is met with a sigh is met with a laugh. And round and round we go.

Most of the laughs are courtesy of Amy Adams, who, after this, must be the best young actress working today. Her use of the word ‘cocksucker’ as though it were a coaster deserves an Oscar alone. The cinematography by Hoyte Van Hoytema is full of interesting things to look at, from a mesmerizing tracking shot early that moves away from the principal characters down a street at an impossible speed, to a beautifully-framed establishing shot of a hotel room by way of a close up of used chinaware. Hoytema and Russell also shoot the boxing scenes to look like 90s pay-per-view, a nice little visual style that separates their ring from the Rocky‘s and Raging Bull‘s of the world.

And though it all must end the way we all know it will (and did in real life, or course), it earns its earnestness. Like the large family that chews up his frame, Russell’s film is a stubborn bastard of a thing, imperfect and self-satisfied but, ultimately, worth sticking with to the end.

Have you seen The Fighter? Do you plan to?