As reporters from The Guardian and The New York Times are shown sifting through hundreds of thousands of leaked documents uploaded to the Wikileaks site by Chelsea Manning (then Bradley) in 2010, the acronym EOF is clearly defined as “Escalation of Force,” in a blatant swipe at the US government’s penchant for unnecessary killing in the Middle East. While the term explains what America did wrong, it’s also relevant to the speed at which Bill Condon’s The Fifth Estate progresses towards its weighted positing of the marketing gurus’ question, “Is Julian Assange a hero or traitor?” Benedict Cumberbatch’s portrayal of the divisive figure may go both ways when introduced as a weirdly charming computer genius eloquently paving a path towards infamy, but as leaks and international notoriety increase, he quickly evolves into a megalomaniacal monster.

This escalation is not at all surprising considering Assange’s staunch online opposition to the film while holed-up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London, but it does derail what begins as an astutely non-biased look. I mean, whether we believe Julian’s assessment that his “intern” Daniel Domscheit-Berg (Daniel Brühl) was suspended before much of what happens onscreen occurred or Berg himself (a spokesperson whose book Inside WikiLeaks: My Time with Julian Assange at the World’s Most Dangerous Website was a source material for the film), only those intimately involved will know the difference between truth and lie, and whose account is more accurate. While an impartial view would therefore have been the most honorable way of disseminating their “historical fiction,” the person at the helm can’t help filtering each detail through his/her own opinion.

The only thing Condon and screenwriter Josh Singer could hope to accomplish is a product that at least tries to look at all sides without painting WikiLeaks as protagonist or antagonist against a world of government subterfuge. To this end they mostly succeed, acknowledging how the site’s anonymous submission process helped take down corruption in the war on information/secrets, while its lack of censure left those brave whistleblowers willingly leaving their names on the documents vulnerable to retribution. In this respect, The Fifth Estate becomes a David versus Goliath enterprise pitting two computer hackers against presidents and kings with the internet’s slingshot winning every single battle. But it’s not a documentary where factual details can simply unfold from start to finish as education. Narrative entertainment needs conflict and there’s no better villain than Julian Assange.

I’m not denying this visionary didn’t have flights of hubristic grandeur before, but Singer’s script finds ways to show how Berg’s level head kept him in check. It’s not out of the ordinary, then, that these two become an unstoppable mad genius/bigger picture tandem carefully traversing uncharted journalistic territory by opening the public’s eyes to how news can be shared without filter. But as soon as the film’s timeline reaches Manning’s leak, all that fantasizing of a new world order erases to expose how integral Berg’s account played in formulating the plot’s trajectory. Harmless interactions of push and pull between Daniel and Julian prove anything but, as a switch flips wherein Berg is anointed good and Assange evil. The supposedly unbiased set-up proves merely conditioning to manipulate our emotions into believing Julian’s a vile, heartless robot.

And maybe he is—especially if just half of the debate between he and Daniel is true, about whether leaking the identities of confidential informants who aided and abetted government cover-ups went against WikiLeaks’ original conceit to protect all whistleblowers. Assange turns ugly and cruel, throwing tantrums for power while becoming vindictive and paranoid towards colleagues he now deemed in opposition to what greed and ego told him was important. Condon and Singer let the subject matter devolve from gradually pushing the blame into Assange’s hands as the film moves along into a complete and utter crucifixion. The Fifth Estate stops being an exposé on the changing climate of media during the internet age and instead starts to teach us a lesson about morality and where the line should be as though it knows better than us.

The filmmakers can tell whatever story they’d like based on whatever sources they believe; they aren’t going to please everyone and no one should expect them to try. History will always be controlled by those who speak loudest, making the validity of what’s depicted here inconsequential unless WikiLeaks finds surveillance footage of every single conversation Assange and Berg had to prove without a doubt it’s wrong. Please just make sure what you have to say is done so with tonal consistency and at least a modicum of authenticity. The Fifth Estate has little of both once it overextends itself halfway through by introducing US government employees (Laura Linney, Stanley Tucci, and Anthony Mackie) and their heartstring tug of a Libyan informant (Alexander Siddig) with no purpose but to wax on about the “greater good” and vilify Assange more.

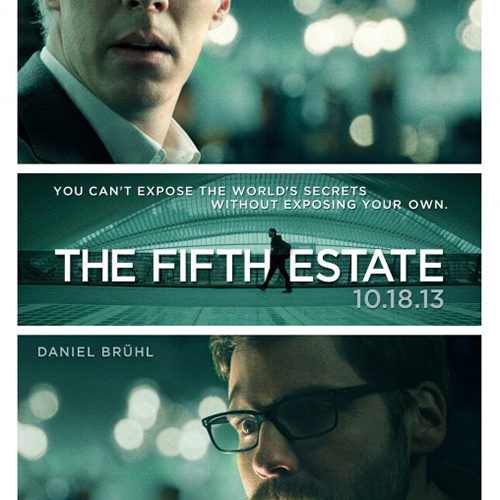

Berg had an agenda just like David Leigh and Luke Harding did while crafting WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy—two of many versions speaking on a force of nature who undeniably did as much bad as good. The Fifth Estate not only condones their view but also attempts to ensure it becomes gospel by giving it the Hollywood treatment. Yes a stellar cast was compiled—Brühl adds a welcome bit of compassionate activism to rally behind while Cumberbatch knocks Assange’s complexities out of the park—and Condon plays with his Breaking Dawn cesarean focus abstractions to add visual intrigue when things get intense, but it rings false nonetheless. Whether an overused office metaphor for WikiLeak’s hot spot deflection, Siddig’s “collateral damage” MacGuffin, or Singer’s vicious character assassination of Assange, it’s all entertaining window dressing masking the real issues.

The Fifth Estate opens wide on Friday, October 18th.