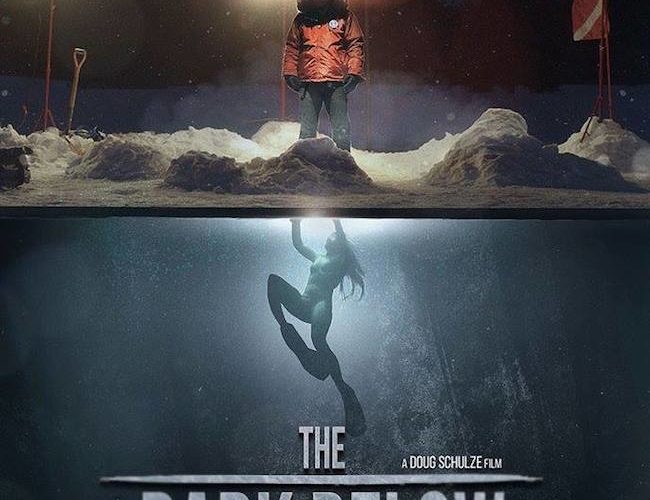

The premise that director Douglas Schulze and co-writer Jonathan D’Ambrosio have cooked up for their film The Dark Below is a bold one. This 75-minute thriller is dialogue-free, save one line at the start setting everything in motion, the story instead unfolding as a series of expressions through current duress and visually informative flashbacks while David Bateman‘s energetic score blasts you into the correct state of unease. Performances must be a bit over-the-top, with sight and sound bordering on manipulative, in order for it all to work, but we hope the result will be good enough to forgive any moments where these inevitabilities go awry. And for a time it is, our intrigue at what’s happening initially getting the better of disbelief. Sadly, that time is too short.

Kudos to the filmmakers for throwing us into the fire with frame one, though. I was genuinely interested because the violence onscreen was simultaneously of-the-moment and wholly premeditated — or so I thought. We see Rachel (Lauren Mae Shafer) being thrown around by Ben (David G.B. Brown), her fear palpable and his malice icily blank. Are they together? Are they strangers? Where are they? It’s all a mystery as Ben suddenly has a glass of water and a red drug of some sort to mix and force Rachel to ingest. Next we’re outside on ice: her groggy in a wetsuit and him chipping away to find water. Is this to kill her or simply dump the body? Why give her oxygen? Just to watch her slowly die?

Nope. It’s not quite that. Time goes by with Ben giving his best Jack Torrance from the end of The Shining until night falls. He rises to return to the site of his assault and check on another victim (Veronica Cartwright). Whatever’s going on is either extremely methodical in ways we can’t yet understand or completely contrived to elongate the run-time well past utility. There are motion lights to detect when Rachel leaves her icy prison and their illumination triggers Ben to return, pretending like he wants to kill her before simply shoving her back in the water. It’s a godsend when flashbacks arrive, because I couldn’t watch this same cat-and-mouse game devoid of suspense without a reprieve. The past’s trite tale of tragedy is better than nothing.

But it isn’t great either. We begin understanding the relationship between these three people and Ben’s apparently deep-seeded psychopathy, but only to discover another open-ended question about the well being of a little girl. The hope is that this is all leading to answers when reality shows the opposite true. We eventually get brought full-circle to the beginning so we can contextualize who these characters are, but we never learn what motivates Ben or why Rachel waits so long to make at attempt at freedom when she knew things weren’t right. And don’t tell me it’s some metaphor about being trapped in domestic abuse. That would only reveal everything to be a misguided usurpation of real horror for one-trick thrills focused on actions rather than causes.

It’s all just noise trying to legitimize the one-on-one slow motion war of attrition waged on this frozen lake. That’s what’s supposed to make us gasp at the edge of our seats and grip our armrests. But this is impossible mostly due to an extremely low budget and lack of nuance on Schulze’s part. The simple fact that the horror riffs are literally blaring in your ear for the duration renders any impact they would usually have in heightening our emotions at key moments moot. Having Ben forcefully shove a knife into the ice at the frame’s center doesn’t worm its way into our subconscious to be all “A-ha!” when Rachel takes it later. It slams us in the forehead with a frying pan to expose every machination.

Fixating on something like Ben’s pain after putting a gloved hand in the frozen water is a misstep too when your lead is submerged in that water for three-quarters of the run-time. Rachel is in a wetsuit, but her face is open besides a pair of goggles. So here we are watching her struggle to get to the surface with bare hands and mostly bare face without any “pain” besides desperation to breathe. You try to disregard it until Schulze follows Ben inside to a stove where he proceeds to warm his nearly frostbitten arm. Is this suddenly a superhero film? Is Rachel immune to cold? If he’s ready to lose an arm after thirty seconds, she should be unconscious after ten minutes. And yet she still fights.

The beginning allusions to premeditation piqued my interest, for I wondered if Schulze was going to surprise us with left turns. Maybe this whole thing was some role-playing scenario between lovers, the water not as cold as assumed, the oxygen tank and lights safety measures to ensure no one got hurt. When that’s proven wrong I became intrigued as to how Schulze would explain Rachel’s lack of exposure sickness: another dead-end. None of these details were included to lead us astray at all; they were merely accidental by-products of budget and script. The filmmakers want us to suspend our disbelief about them without realizing their inclusion renders it impossible to suspend anything. It’s one thing if The Dark Below sought campy implausibility, but it craves legitimacy instead.

So when Rachel finally does show signs of frostbite (on her second escape before the blackness on her skin disappears again upon re-entering the water assumedly due to make-up issues) we breathe easy knowing science isn’t ignored. And when her finger falls off we chuckle, applauding the decision to make the water as much a foe as Ben. If Schulze embraced the inherent cheese, however, we’d laugh hysterically because we see her knuckle, the finger curled inside her palm. If this were an Ed Wood-type D-list romp we’d giggle with the film when that hand turns to expose the ruse. Instead I laughed with pity and disappointment. It was the final coffin nail into a cool cinematic idea that never finds the execution needed for success.

The Dark Below opens Friday, March 17th in L.A. and Friday, March 24th in NYC with more cities to follow.