The Collection is a rare horror film that touches a nerve, although perhaps I was in a receptive mood. Indulge me for a moment: the film is a fetishization, even memorization of the scene of horror — add in the voices of the victims and I might have reacted with the same tears I have reserved for repeat viewings of Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog.

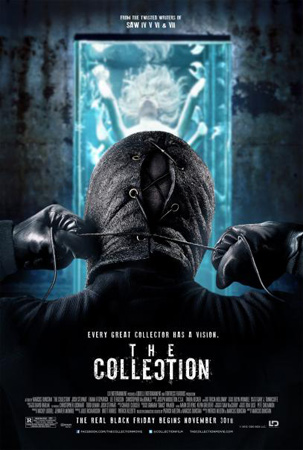

Perhaps I’m reading too much into The Collection, which is an effective experience that I don’t want to have again. Much is artificial right down to the manufactured emotions of the film’s opening scene. Our heroine Elena, we learn almost died in a car accident as a young women, and her powerful father Mr. Peters (Chris MacDonald) vows to keep her safe, even if it mean assembling a SWAT team to take on “The Collector”. The Collection, I now know (but didn’t upon walking into the theatre) is a sequel to The Collector, a 2009 feature also by Marcus Dunstan who shares writing credit of the last four Saw features.

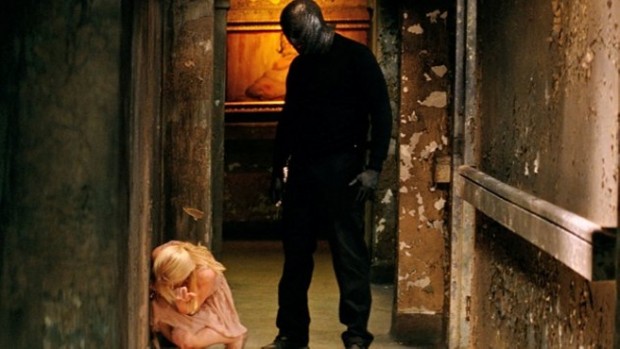

The formula isn’t fun despite having the pretense of fun. Whereas Saw provided active engagement in the form of clever traps, The Collection is a pure slaughter akin to James Holmes’ apartment — no one should be forced to go into this abandoned hotel sitting on the edge of town, and what we find inside is truly deranged.

With a wickedly short running time of 82 minutes, the film rejects the game structure similar to Saw (although lacking the wit of those films). Those were victims; here, we have self-selected groups that will do what the police won’t to track down Elena, by entering into this maze. Jigsaw is a conceptual artist with others carrying out his mission, while The Collector (played by Randall Archer) has seemingly constructed a concentration camp straight out of the archival footage of the aforementioned Night and Fog.

Irony briefly exists in the film’s select moments of joy and perhaps wit, namely a dance party created with the precision of a Ke$ha video that turns quickly violent. Horror depends on tempo and this scene of an automated massacre is as disturbing as the unedited footage I’ve seen on YouTube of the Station Night Club burning down.

And perhaps this is the point, or dare I say brilliance, of The Collection — it is artificial, a cruel construction that effectively gets under our skin. It’s artifice includes poor performances, however it edges towards something that transcends what should have been a schlocky direct-to-video experience. Thus here is the greatest case of seeing this movie, while you can, on opening weekend — or perhaps a case against it: a horrific event experienced as in a collective setting somehow becomes more disturbing. Giving voice to the victims, like news coverage aims to do after a tragedy, is one way of inspiring true terror. If only this film had gone this extra mile it would have been a paralyzing experience crossing the line, while calling out every other horror film.

The Collection is not a great film, and it may be gone from multiplexes next weekend, but it certainly works in spite of itself and perhaps without responsibility for what its really doing. Unlike the most enjoyable films of this genre it doesn’t put out good vibes — it’s not about that. While horror is not a genre that’s synonymous with social responsibility, this somehow effortlessly achieves something very disturbing beyond its rather lame and often too slick mise-en-scene.

The Collection is now in wide release.