When it comes to most films, the concept of a hero and a protagonist are one and the same, and so the two are assumed to be synonyms. The truth is that a protagonist is the main focus of a story, the person through whom the narrative flows, and the hero is the person who is trying to achieve the morally virtuous goal. It is entirely possible to take a villain — “a bad guy” — and make him or her into the protagonist of a story without compromising the inherent wickedness that makes them a compelling counterpoint to the heroes we are used to.

If someone had only explained this to writer-director David Ayer, the narrative promise of Suicide Squad might not have been lost in a sea of reluctant hero clichés and banal superhero action set pieces.

It is truly staggering just how rote and obvious the story of this movie is considering the high-concept spin it puts on the average comic book film. In place of spandex-clad heroes, a world-ending catastrophe must be averted by a gang of ruthless villains who have been strong-armed by a secret government program into working on the side of humanity. This is at once a novel concept and an easy sell, and, to the film’s credit, it does not waste this totally. It does, however, find a way to make a story that should be dangerous and edgy into just another dull tale of superhumans doing super things.

One of the biggest and most enduring issues with Suicide Squad is its complete incompetence in establishing and maintaining characters. Any film, regardless of genre or cast size or budget, has to spend a certain amount of time introducing and developing an ensemble. The laying of backstory and foundational knowledge for the principle players is one of the most important parts of creating an engaging narrative. Suicide Squad somehow manages to spend a laborious amount of time on this aspect while simultaneously failing to build adequate understanding or comprehension of its villainous cast.

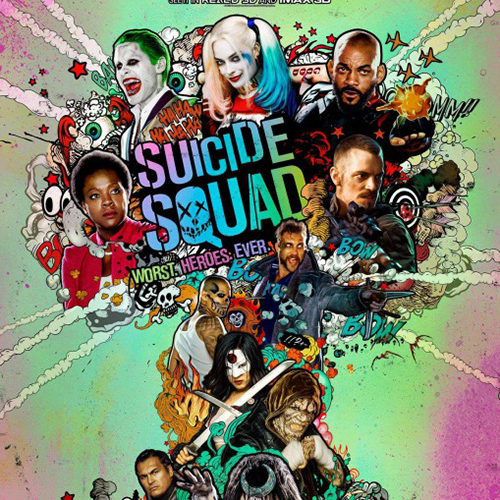

The bungling of basic character set-up starts almost immediately. The pre-credits sequence introduces us to a Louisiana Black Site prison where some of the worst-of-the-worst criminals in creation are kept. We see Deadshot (Will Smith) being served disgusting food while being treated with disdain. Then, we witness Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie) getting talked down to, insulted, and electrocuted. Following this, we get an extended dialogue scene that introduces us to these same characters in flashback so that we can see what they used to do and how they got caught. Not only that, in this same scene, we are shown a series of other character flashbacks for people we have yet to meet, and who will take disparate amounts of time to become essential to the active story. All of this takes far too long, and yet somehow leaves one wondering exactly how the movie wants us to feel about these people. Then, right when the film is entering act two, two other characters are tossed into the mix, and one of them also gets a flashback.

This is calamitous storytelling. It is as though someone took every idea for how and when to introduce their characters and decided that the best course of action was to try them all. What is lost in service of this over-abundance of ineffective character-building is any sense of story progression. Thanks to the fact that almost the entirety of the first act is devoted to building the cast, the inciting conflict that creates what could be referred to as the plot arises out of nowhere and leaves one feeling paradoxically as though not enough time was spent on backstory. The relationship between Rick Flag (Joel Kinnaman), who leads the titular team, and Enchantress (Cara Delevingne), one of its members, is essential to the story and climax, yet is given perhaps a minute of total screen time. When the time comes for this emotional conflict to pay off, the lack of work put into bringing this emotional connection to life deflates whatever appeal there might be in the moment.

That lack of attention to customary narrative construction could probably be attributed to the general lack of care taken with the script as a whole. Almost the entire second act takes place with the characters moving toward an objective that neither they nor the audience know, making tracking of their progress or investment in the same nearly impossible. Various other plot points are kept shrouded in mystery, and most times, when the truth is revealed, it turns out that the enigma being alluded to by the characters was actually something the audience already knew.

The whole movie is burdened in this way. Almost every character is given one note to play through the whole film, and is portrayed in a way that makes them more of a victim than a villain. Smith’s Deadshot is funny and charming, but his relationship with his daughter and his job as a hitman makes his badness feel fairly white collar. Harley is a weird wonder to behold, but the story of her genesis leans heavily on her emotional and physical abuse at the hands of the Joker (Jared Leto) and yet, still, plays their attempted reunion as something of a triumph. Had this theme of pain and loss leading to evil acts been explored in a meaningful way, it could have been an interesting tack to take, but it wasn’t and it isn’t. Diablo (Jay Hernandez) comes closest to feeling fully and effectively realized. If any emotional moment lands in the way that it is meant to, it belongs to him, though the twist in his narrative is nothing one couldn’t guess from his introduction.

Muddled characters and uneven storytelling are the roots of the issues here, but the ways in which Ayer seems to try to cover up his film’s deficiencies grate most of all. The soundtrack is filled with pop hits that speak so directly to the narrative that they actually become slightly insulting. These needle-drops occur with such frequency that their novelty wears off by the end of the second set of character introductions. Grimy cinematography and the uninspired direction do nothing to ameliorate these issues.

In spite of all of these nearly fatal flaws, there are still moments of light pleasure within this dull and airless venture. Smith and Robbie have good rapport, and each of them is responsible for the film’s most potent moments of levity. Hernandez creates some absolutely moving scenes. But these few bright spots are smothered beneath everything mentioned above and some other truly tragic choices, such as the villain’s aesthetics and their attendant doomsday device, and everything having to do with Leto’s Joker. What should be Suicide Squad‘s two most riveting and intense aspects more often play as laughable attempts at uncharacteristic oddity. The film is so stuffed with otherworldly elements that are treated as commonplace that the audience can’t help but respond with the same malaise as the characters. A woman has a sword that holds the soul of her husband, and that information is dropped as an afterthought right before the final battle.

Villains as protagonists working to save the world should have been a strange, delirious treat. Suicide Squad plays it as just another walk in the comic book movie park. It’s a sad, disappointing fate for what could have been one of the more eccentric and fun tentpole films of the year.

Suicide Squad opens nationwide on Friday, August 5.