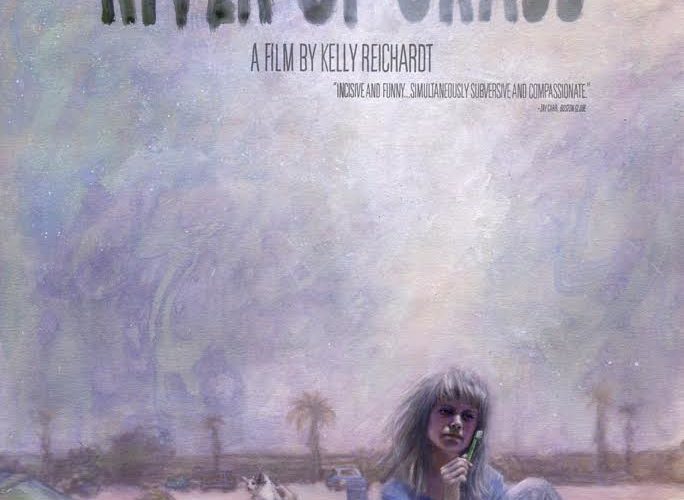

Kelly Reichardt’s River of Grass is a “lovers on the run” film, but the main characters aren’t lovers, and their version of the lam is spending a few days at a flop-house in an adjacent zip code. Originally released in 1994, Reichardt’s debut is a digressive walkabout into a world of delayed responsibility and halted potential. It’s a story that perfectly aligns with the mythic Americana themes that have emerged over her career, while also feeling formally radical. Rereleased this year through a Kickstarter from Oscilloscope Laboratories, River of Grass isn’t able to reach the peaks of Reichardt’s later monumental work, but it’s educational in mapping out her concerns as a filmmaker and a stirring reminder of her abilities as a visual stylist.

River of Grass sketches out the story of two spiritual bedfellows, Cozy (Lisa Bowman), and Lee Ray Harold (Larry Fessenden), who together descend into a loop of graceful panic after they believe that they’ve accidentally killed someone after a night of heavy drinking. Cozy is a restless soul, a mother and wife who despairs about an already written future with a loving husband she doesn’t love and kids she barely tolerates. Above all else, she really wants a new life, but her happiest moments come in a time of deepest limbo when she’s puttering around smoking in a motel, or becoming entranced with sultry jazz records.

Lee is a thirty year old ne’er-do-well living with his grandma, who’s torn between his desires to have a functional life, or to sink into the romance of taking that life. For him, a life of pickpocketing and a holstered gun seems like a gateway to this higher form of life, but his crime sprees are rarely more glamorous than trying to grab quarters from payphone slots or stealing some hapless sucker’s clothes from a local laundry.

Adjacent to their half-formed escape from society, the story checks in on Jimmy Ryder (Dick Russell), Cozy’s father and a jazz drummer turned private detective who’s been disgraced for losing his gun in a robbery that has coincidental connections to Lee. Aware of his daughter’s disappearance, Jimmy slowly pieces together the non-story, and wonders why his daughter has suddenly decided to take a pit-stop on her way to adulthood. Reichardt isn’t particularly interested in the details of his actual life, but she does find a way to build his life through the random items in his home or brief flashbacks that serve as windows of who he was in those exact moments.

River of Grass feels defiantly different than Reichardt’s future filmography, but there’s still a stubborn sense of moral equilibrium – a constant tugging sense that even romanticism is hollow when reality is based on a defined order of who deserves a life of pleasure or pain. As much as Cozy and Lee’s characters would like to feel like they are floating in some ethereal space of limbo – untouchable by a world that’s stuck in a rut of untroubled routine – they’re plagued by the same everyday problems of trying to pay the rent and find a place called home.

Set in Florida’s Miami-Dade county, this sunshine state is less a tropical hideaway than a run-down place of half-built dreams and everyday philosophers repeating bad jokes in the hopes that they’ll make sense down the line. And while its formal acumen feels entirely distinct from the rest of her oeuvre, there’s still a recognizable sense of mood as a spiritual sense of being. Like the rest of her films, feeling homeless is a physical state, but it’s also a lingering form of alienation.

Reichardt has practically become known as transgressive in her emotive use of stillness as a modulation of mood. But River of Grass feels swift in comparison with its flurrying editing style that’s as likely to dabble in Chris Marker-style collage photography as Claire Denis-esque rhythmic cross-cutting. A sequence that tosses back and forth between Dick’s increasingly martial drumming patterns and a person curling their eyelashes shows that even early on, Reichardt had a singular way of making process into something experiential.

Still, there is something occasionally strained about River of Grass’ confluence of poetic symbolism and juxtaposition of apathy and romance. Whereas dialogue has become nearly peripheral to narrative in her later work, this film is characterized by monologues from Cozy with a nearly prophetic tendency to foreshadow the contours of the storytelling. And the dialogue is similarly filled with a few too many moments that feel wedded to a schematic of the story’s evolution rather than a spontaneity built from character.

Rather, it’s more productive to view the entire picture as an essay about empowerment nestled in the well-worn archetype of the outlaw story. Reichardt taps into the framing as an elemental feeling of comforting alienation. Evoking the dialogue in Meek’s Cutoff about women being built on chaos and men being built on destruction, River of Grass is as much about the comfort of trouble as the anxiety in wiping that same slate clean. And, in the end, it has far more in common with Belle de Jour or Jeanne Dielman than genre staples like Badlands, even as Fessenden’s nervy body language is a dead ringer for Martin Sheen’s tilted symbol of desperation in Malick’s film. But as the film reaches its nearly perfect finale, it still can’t help but feel like a minor detour in a career-long road trip.

River of Grass is now in limited release and available to stream on Fandor.