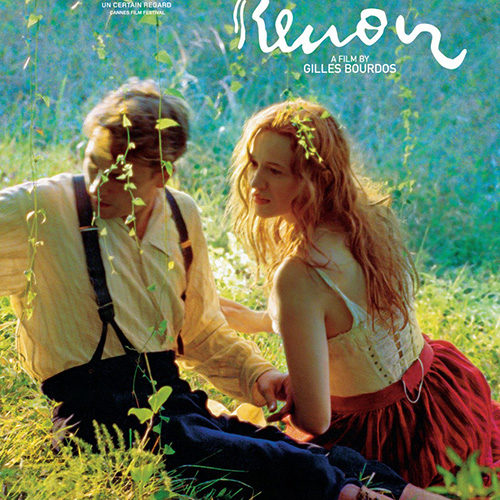

A name as prolific as Renoir can’t help conjure a litany of tales worthy of the big screen. None, however, are more intriguing than the discovery of the surname’s most famous owners—Impressionist painter Pierre-August and his film-directing son Jean—sharing the same muse. Despite its title then, Gilles Bourdos‘ Renoir is in many respects actually Andrée Heuschling’s (Christa Theret) story. A young dreamer aspiring to become an American actress, the fifteen year old arrives at their family retreat in Cagnes-sur-Mer circa 1915 at the behest of Pierre-August’s (Michel Bouquet) late wife. Jean (Vincent Rottiers) returns from the frontlines of WWI to convalesce a leg injury not long after, ultimately falling for the beauty posing nude opposite his father’s easel just as his nationalism threatens to put him back into the fight.

In part based on Jean’s brother Pierre’s grandson Jacques‘ fictionalized history of the family, Table Love, Bourdos and co-writers Jérôme Tonnerre and Michel Spinosa have crafted a very intimate portrayal of two artistic geniuses crossing paths during one’s twilight and the other’s birth. It’s a far cry from either’s glory days as Pierre-August must have his hand taped to hold a brush due to crippling arthritis while Jean sits lame and at a crossroads in his life. Pierre (Laurent Poitrenaux) too has been injured in the war, younger brother Coco (Thomas Doret) exists as a veritable orphan with discipline problems, and pseudo sister Gabrielle (Romane Bohringer) has left to start a family of her own. So, before Jean’s welcome return, the estate was simply a bunch of maids/models and their 74-year old boss.

The tale is not a salacious one, though, where father and son vie for the affection of the same girl—in fact, Pierre-August has no romantic/sexual desire in Andrée other than painting her flesh onto canvas. If anything, he’s happy Jean may see her as a reason to stay and forget the war he so desperately yearns to rejoin. The boy has nothing but a hobbyist enthusiasm with film, his lack of skill and ambition being why he enlisted with the cavalry anyway. No, his newfound love for this vision brought into their lives becomes the first thing he’s been able to cherish since the drive to defend his country took over his soul. But while her adding him into her dreams of movie stardom gives purpose, it may not be enough.

In the end, all the Renoir boys are shown as lost children desiring the love of a father they’ve never explicitly received. It may be a surprising revelation considering Pierre-August’s sweetly moving, imagined conversation with his dead wife, but Jean’s telling Coco he’d never heard their father tell her his feelings either shows the truth. The elder Renoir was a volatile man, self-described as possessing a mean temperament his wife quieted throughout the years despite what is assumed to have been many affairs with his models. Now with mortality staring down, however, and her calming touch no longer present, his life has transformed into nothing more than painting. And while he may covet Andrée’s body, it’s only for her shape and skin—the female form wielding a power he’s never matched otherwise.

This is why she’s so important to his life and career, rejuvenating his art and his compassion in the sons he was always quick to chastise but never outwardly love. She also isn’t just some girl off the streets willing to do whatever’s necessary to horn in on the Renoir name and money. She’s a performer on a job and far from the other girls dismissing her as one of them—models turned maids accepting the life given them at face value. Andrée doesn’t hold Pierre-August with their reverie; he’s her boss and anything more ends at a fatherly appreciation. Jean’s the one who provides her with more, but the increased selfishness of both men makes it hard to trust she’s earned a place beyond that of the whore they unwittingly make her into at times.

She battles with finding her place, yet never settles. Pierre-August strives not to retire from his work despite being saddled in a wheelchair and in such pain. And Jean reconciles his feelings for an unknown future much scarier than the prospect of dying in a war with honor—the only form of it his mind believes he may yet earn with an existence laying in the shadow of a legendary father. These are subtle, emotional evolutions that unfold carefully and slow from the moment Andrée enters the Renoir’s French Riviera retreat to when Jean leaves it once more. And while none provide the film with any memorably bombastic conflict to be solved, they each provide insight into the human condition, the price of celebrity, and the struggle to carve one’s own path.

Bourdos and cinematographer Ping Bin Lee paint their canvas in vibrant, impressionistic colors recalling Pierre-August’s famous Luncheon of the Boating Party as well as Georges Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte courtesy of those unmistakably period-specific umbrellas. Mention is made of Renoir’s appreciation of Titian and the amount of time Theret spends nakedly reclining makes her into his Venus of Urbino, always accentuating her curves to the point where she jokes he paints her too fat. The aesthetic therefore captures the time perfectly just as the performances breath life into behind the scenes maneuvering on the timeline of two greats. Theret is a hurricane of self-worth, Bouquet a prideful yet understanding taskmaster, and Rottiers a likeable idealist who’s seen too much death for a boy of twenty-one.

Renoir captures this trio at an important moment in their lives with a keen eye for detail that may provide too much information. Time progresses quickly as decisions crucial to plot progression are made off-screen before being told to those involved—something that often makes the close to two-hour runtime seem short. But the quiet moments of painting and scenery depiction unfold as though they’ll last forever, the camera delicately capturing the reflections of light Pierre-August paints as though telling us visuals always trump narrative. A lot happens this summer as characters like Pierre randomly appear while those like Coco engage in moments beyond my comprehension—what’s with his putting paint on a sleeping, nude Andrée? It’s a gorgeous piece of cinema that unfortunately never made me want to dig deeper than its surface.

Renoir is now available on VOD.