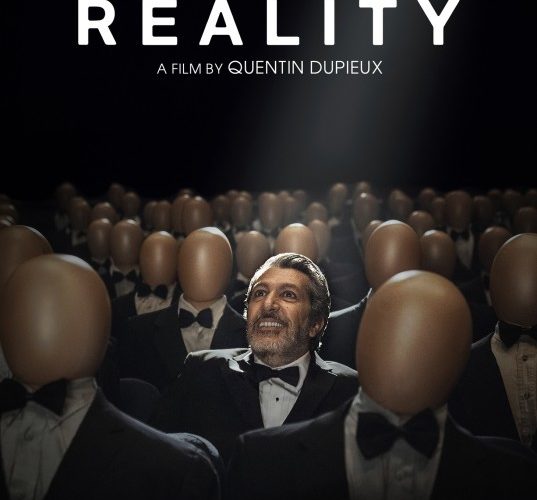

This is what it’s like to go insane. Writer/director Quentin Dupieux loves the surreal and absurd, but Réalité [Reality] takes his penchant for humorous oddity to another level. With Philip Glass‘ “Music with Changing Parts” boring a hole into your temple and fluid sequences of characters meeting in real time or via some from of media projection (and sometimes both at once), the filmmaker revels in keeping his audience off balance and unsure. The beauty of it this time, though, is how he provides us something to look forward to besides any false hope for clarity. No matter how insane things become or how impossible, our only desire is to discover what’s printed on a blue VHS cassette found in the bowels of a boar. The suspense is authentic and the reveal as simple as it is obvious.

I feel as though I’m in a trance—the repetitive nature of Glass’ self-produced melody from a 1970 LP having lulled me into a waking coma with slack face and cloudy eyes a la Jack Nicholson in Stanley Kubrick‘s The Shining (an apt reference as the late director is mentioned with hostility mid-way through). There’s something mesmerizing in its creepy horror flick intent used as a leitmotif whenever one of Dupieux’s characters finds him/herself falling off the edge of a psychological cliff. We hear it and a switch flips, stiffening our backs to sit up straight and pay attention to what happens next. Where at first we begin to hypothesize everyone fitting together coherently, we soon realize the film’s title is describing a concept it doesn’t possess. Or perhaps it’s a concept that doesn’t actually exist.

Reality is manipulated on many levels whether literal (the idea that what we see is an actual occurrence of characters existing within their plot); figurative (the duality of dream and waking life converging on top of themselves until the subject of both confuses one for the other); personified (Kyla Kenedy‘s curious young girl who stumbles upon the aforementioned VHS is named Reality), or disassembled (a transference of vantage points where the reality of a situation proves “real” on multiple levels of its own construction). I’d be surprised to learn that even a single second of Dupieux’s work was meant as reality. That’s not saying one or more characters don’t exist or that one or more is manifesting the others inside his/her head, only that we never escape this prison of electric imagination to know for certain.

Is Reality in control: an inquisitive girl who’s seemingly the subject of a quasi-documentary lensed by Zog (John Glover) as well as a child living amongst the rest outside cinema’s realm? Is Jason Tantra (Alain Chabat): a TV Show camera operator yearning to helm his debut feature about televisions that kill humanity with waves capable of exploding flesh? Is Dennis (Jon Heder): the host of the show Tantra films, dressed as a rat while battling an eczema outbreak on air? Or are they all the same: a schizophrenic fracture of psyches buckling under the pressure of reality that now live together in a nightmarish community where time folds in on itself? Reality as a world or state of things that exists is a misleading definition since we’ll never know or experience anything not witnessed through our personal filter.

So while we begin to relate to someone as the lead—someone we trust is “real” above those surrounding him/her—we forget to view ourselves as meaningful within its fiction. The reality is our watching of a work of art; simultaneously letting it unfold through the mind of its creator and our own interpretive transference of his intentions. Dupieux merely adds the wrinkle of allowing his characters to also interpret themselves. He’s the conductor, spinning them together until they collide in life, dream, and imagination. And we are the receiver of each humorously confusing collision. The nightmare therefore becomes ours as we see ourselves in every one of these lost souls just as they see themselves in each other. We are all the same: slightly different versions of man living identical drama, anxiety, hope, and love.

After all, does anything truly occur without a second person’s corroboration? Look at Eric Wareheim‘s Henri as an example. Here’s a man driving a military jeep while wearing a dress. We’ve already seen one assumption of reality debunked as fiction before his introduction and that vignette is shown to exist in his world. So, when Henri suddenly is seen in the office of his psychiatrist (Élodie Bouchez‘s Alice who is also Jason Tantra’s wife) relaying a dream, we find ourselves drowning in frayed strings of connection. We’re forced to see every scene as lived by one character and corroborated by another. Reality’s existence is proven false because Zog films it. Jason and Alice must be real because Jason meets Zog. Henri must too because he knows Alice. So how can Reality see him in that dress?

Perhaps a better question is why we can so easily dismiss one reality for another based purely on mankind’s conception of it. This is a film and as such everything that happens within it is fabrication. So what’s the point of declaring Jason real and Reality fake when their origins are equally false? Why do our feelings of poor health become figments of our imagination when a doctor cannot see them? Why do we give him complete confidence in a way that renders what we know with certainty inconsequential in comparison? These are the ideas Dupieux sets forth—ideas a barebones synopsis about how Jason is tasked by his producer Bob (the splendid Jonathan Lambert) to capture an Oscar-worthy groan of pain for funding does disservice. What is the perfect anything when objectivity is a lie?

Reality opens in NYC and releases on VOD Friday, May 1st, followed by a Los Angeles release on May 15th.