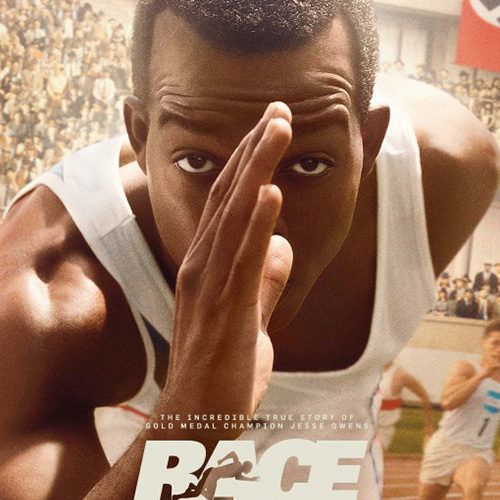

Stephen Hopkins’ Race focuses on Jesse Owens (Selma’s Stephan James), a legendary African-American runner who won four gold medals in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, but never quite received the acclaim he deserved, thanks to virulent racism and a country that only pays attention to you when you’re winning. To Race’s credit, it tries to express these complicated circumstances through an adjacent look at the behind-the-scenes process of America deciding whether to participate in the Olympics at all, and subsequently Owens’ own crisis of faith about whether to attend, but it lacks a coherent perspective to link together all these disparate parts.

From the beginning, Owens is the consummate underdog on the way to success, literally weaving in and out of an impoverished Cleveland in 1933, to say bye to his family before heading off to college. The script is full of telegraphing platitudes like Owens telling his terminally unemployed father that “things are going to turn around, you’ll see.”

At Ohio State, Owens immediately demonstrates his running skills, sprinting around the campus track, but no one around can look past his skin color. That is until Larry Snyder (Jason Sudeikis), the commanding, easily undermining coach of the team, spies Owen and clocks a record breaking sprint on the track.

Snyder is a demanding mentor, vicariously living through Owens after failed dreams, and pushing Owens to his physical breaking point with marathon training sessions and around the clock prodding. He also has an unfortunate habit for invoking respectability politics and crawling into the bottom of a bottle.

But Snyder’s most important contribution has nothing to do with training at all, but rather the ability to block out the consuming noise. This being a time of embedded racism, Owens is regularly the brunt of racial slurs like “gorilla” and equally unflattering insults, and it’s as much a hurdle to ignore these attacks as it is to just run.

The film’s two most visually compelling scenes have Hopkins playing with audio cues and a shuttering frame to convey a feeling of zoning out. In perhaps the best sequence, Snyder speaks with stunning clarity amidst people screaming all around him in a locker room. It’s a visual sensation that, combined with slow motion, pays dividends throughout, but also goes to show that the film itself has very little to offer in their relationship other than an admittedly sweet camaraderie and this near superpower.

More frustratingly, much of the conversation about race amounts to mansplaining by white people about what African-Americans face, and by the end, the script can’t decide how to effectively comment on the combination of token nationalism and race relations within the story without simply going for the easy pleasure center sports story moments as a version of triumph over racism.

Owens, too, is kind of a wash as a character. He’s a regular boy scout, setting aside money for a wedding to his long time sweetheart, Ruth (an endearing but slight Shanice Banton), and facing minute obstacles in his journey to stardom. Played by James, he has an appealing softness to his personality that contrasts with the usual arrogance of sports stars, but he’s also blandly saint-like. Even his deviation from Ruth with a teasing woman at a Harlem jazz club feels entirely perfunctory, as if the script needed to just manufacture personal conflict and create a stronger sense of agency. The pacing also struggles to find a sweet spot in telling all of the stories, forcing Owens’ story to rapidly progress at random moments.

And while two-thirds of the film follows Owens’ journey to the Olympics, the remaining time is devoted to an intriguing but underdeveloped story of Avery Brundage (Jeremy Irons) going to Germany to decide whether America should even attend the Nazi-hosted Berlin Olympics. Irons is a welcome presence, bringing a brittle authority to his line delivery, but he’s also wrapped up in a narrative development that falls completely flat. For anyone’s who opened a history book, they’ll know that this visit is entirely a narrative formality, and it just doesn’t add much other than foreshadowing the ways in which Germany doesn’t keep their promises.

Worse still, the portrayal of the Nazis in the film is barely above that of the B-movie monsters of Inglorious Basterds. There were definitely a few times where I expected Aldo Raine to just burst in without an invitation. And as far as the historical figures, Adolf Hitler, is relegated to a few glimpses as a doppleganger, while Joseph Goebbels (Barnaby Metschurat) has a larger part as the person in charge of the Olympics. His role mainly consists of a stiff upper lip, a sinister expression, and some hateful asides though.

By far, the most compelling part of the German storyline is the intercession of propagandist filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl (Game of Thrones’ Carice van Houten), who’s hired by the Third Reich to make a film about the glory of the Berlin Olympics. Riefenstahl is a divisive figure, an influential filmmaker who’s been reclaimed by cinephiles in the last few decades with a major asterisk. And van Houten genuinely embodies the character with a warmth and passion as she risks life and limb to make the best film possible, whether it honors Germany or not. It’s unclear how much embellishment is going on with Owens and Riefenstahl’s relationship, but their shared love of sheer skill is more moving than almost anything else in the film.

Still, the conversations about sport superseding politics are undeniably relevant in a time when racism is ignored on a regular basis when sports are involved. And while every line of dialogue near the end reeks of self-importance, the historical impact lifts up those moments. But Race can never quite keep up with its own relevance, and even the last scene feels strangely anti-climactic as if a rail-thin snapshot of a decade of Owens’ life was the only thing worth seeing. Race is the rare biopic that needs more of its own main character.

Race opens in wide release on Friday, February 19.